A Survey of British Fingerstyle Guitar from the 1960s to the Present

It’s November 1984, and a folk club in Exeter, England, anxiously awaits the arrival of Davey Graham. Ten minutes to show time the room is packed, but there hasn’t been any communication from the guitarist. Hope is beginning to fade when a tall upright figure appears in the doorway. In one hand he clutches a worn nylon-string guitar, a tangled nest of strings dangling from the headstock, and in the other a smoking joint. Pushing to the front, Graham begins to play long, rambling instrumentals, interspersed with breaks for tuning but no introductions. It’s shambolic, and by the time it’s over many of the crowd have left. Bizarrely, that night, when he stays with one of the organizers, Graham reels off beautifully constructed Moorish tunes, ragas, and blues until daybreak.

There’s no shortage of stories about the guitarist, sometimes billed as Davy Graham, who died in 2008 at the age of 68. Many of them are apocryphal, but they cement the mystique of a musician whose influence on a whole generation of British guitarists—equally phenomenal players such as Martin Carthy, Bert Jansch, and John Renbourn—is immeasurable. Collectively, these musicians created a body of work that set the template for modern guitarists from Martin Simpson to Laura Marling—while helping extend the expressive range of the steel-string guitar in general.

A Splashy Debut

Graham’s Folk, Blues & Beyond, released in January 1965, shook the acoustic scene to its core. The album was as sensational in its way as Jimi Hendrix’s revolutionary debut 18 months later. From the jazz of Bobby Timmons’ “Moanin’” to the haunting Arabic-tinged “Majuun (A Taste of Tangier)” to covers of traditional folk standards like “Black Is the Colour of My True Love’s Hair” and shots of blues courtesy of Lead Belly’s “Leavin’ Blues” and Willie Dixon’s “My Babe,” Graham’s musical palette knew no boundaries.

A compulsive and inquisitive traveler, Davey Graham soaked up influences like a sponge; Folk, Blues & Beyond was a summation of everything he’d heard. During travels to North Africa studying the oud, trying to come to terms with this ancient Arab instrument, he devised DADGAD—which is now, of course, one of the most common open tunings.

Although Folk, Blues & Beyond brought Graham widespread acclaim, he was already an established presence on the UK acoustic scene. He’d notably recorded with the revered traditional folk singer Shirley Collins on the 1964 album Folk Roots, New Routes. The combination of his Gibson J-45 and Collins’ English-rose traditional singing was viewed as heresy by some folk circles, who thought the music should be performed a cappella. But Graham’s approach to accompanying the traditional tunes was groundbreaking, to say the least.

A collaboration with bluesman Alexis Korner on the EP 3/4 AD yielded “Anji” (see transcription in AG’s April 2016 issue), an unlikely merger of Big Bill Broonzy and a Baroque bass line and the deceptively simple-sounding tune to which he will always be linked. For those that could learn it, it would be their passport to folk club bookings throughout the land. Musically both mysterious and innovative, “Anji” evoked the dark muscle of Delta blues yet hinted at the discipline of European Baroque and the freedom of modern jazz.

Bringing It All Back Home

The 1950s British music scene existed in a grey monochrome world; only the aural battering ram of rock ’n’ roll offering teenage salvation. For a while there was also skiffle—knockabout American folk songs thumped out on plywood guitars, washboards, and tea-chest basses, with musical ability entirely irrelevant. Small wonder that when Big Bill Broonzy and Muddy Waters toured, the bluesmen were greeted as emissaries from another planet.

ADVERTISEMENT

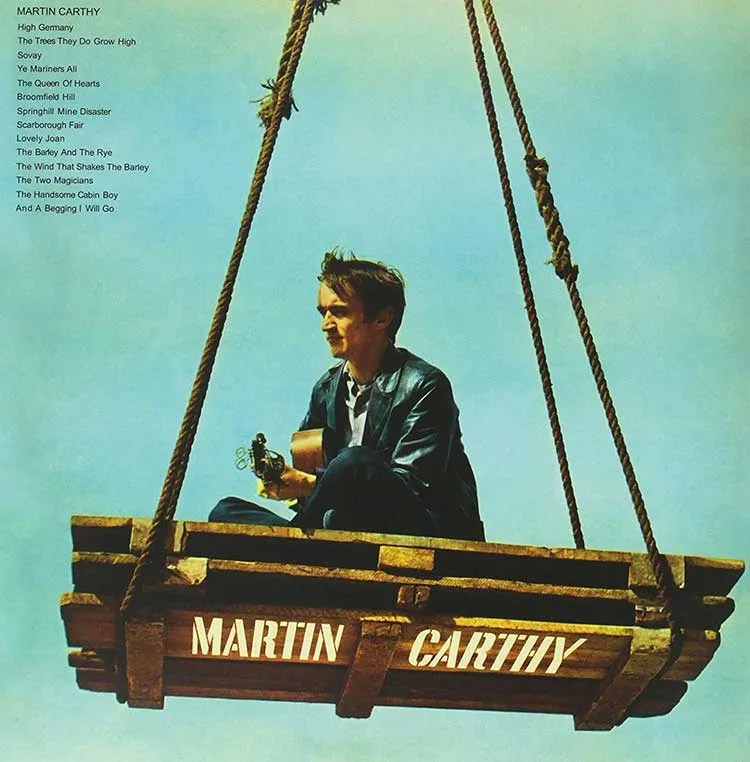

Like most of his generation, Martin Carthy fell under the spell of the blues. If you’re fortunate, you’ll still find the venerated elder statesman of English folk playing one of the small clubs where he began his career in North London. They’re his church and always have been. This quiet, gracious man has inspired a host of imitators. Dylan heard Carthy play and lifted “Lord Franklin” for his song “Bob Dylan’s Dream” and adapted “Scarborough Fair” for “Girl From the North Country.” It’s a debt Dylan has always readily acknowledged. Not so much Paul Simon, whose version of “Scarborough Fair” helped kickstart his career, yet Carthy’s influence went unacknowledged, something understandably galling. It wasn’t until 2000, when Simon invited Carthy to join him onstage to sing the song, that an unspoken rift between the two men was healed.

In any case, Carthy’s taste in music was extremely eclectic. He was spellbound upon encountering Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar in concert, and the pivotal point in his career was hearing Sam Larner, a Norfolk fisherman, sing “The Lofty Tall Ship.” This sparked Carthy’s fascination with traditional English folk music, realizing that much of American folk, bluegrass, and blues had roots traceable back to the British Isles and specifically England.

Unable to perform the traditional folk pieces in normal tuning, and eschewing any idea of playing the banjo, Carthy recognized the need to come up with something new. He’d heard Davey Graham playing in DADGAD but admits he couldn’t get on with it. His answer was D A D E A E, lowest string to highest, a tuning that enabled him to play “the English tunes, treating the guitar in a more linear way rather than harmonic, almost playing the instrument as a fiddle and forgetting about chords.”

Carthy says it took a long time to feel comfortable with the style, but his current preferred tunings—C G C D G D and C G C D G A, played on heavy-gauge strings—enable him to play in half a dozen keys. (His style, he jokes, is Travis picking, trodden upon to make it work for English traditional music.)

And it was all worth it. Carthy’s early albums—littered with tales of murder, myth, and magic, performed with his original tunings and unexpected rhythmic approaches to traditional songs like “Seven Yellow Gypsies”—were truly innovative.

Carthy began his career on a Gibson L-00 with aftermarket block inlays bought in a second-hand shop for seven pounds, ten shillings (about eight dollars), but in 1963 switched to a Martin 000-18, a model he still plays in concert. In 2003 C.F. Martin & Co. issued a Carthy signature model, the 000-18MC, which, like his original, features a 24.9-inch scale fretboard and a thicker saddle for the bass strings to accommodate his slack tunings. The guitar also incorporates a zero fret and the type of wider neck (1.75-inch nut) associated with Martin’s longer-scale OM.

During the late 1950s, Carthy was a regular at the Troubadour, in Earl’s Court, London, a coffeeshop and magnet for visiting American musicians. Richard Fariña, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, Tim Hardin, Loudon Wainwright III, and countless others have all mounted its small stage, and it was at the Troubadour in 1961 that Carthy introduced Bob Dylan to the traditional English tunes he would later adopt. Fledgling venues like the Troubadour would bear witness to the emerging style of folk-Baroque, the distinctive merging of American fingerstyle guitar and modal English folk music.

Far Off the Grid

American Beat icons Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg lent a mystique to the UK folk scene, and visiting musicians like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott were also hugely influential. Songs associated with Elliott, like “San Francisco Bay Blues” and “Cocaine,” became a staple of any self-respecting folk singer’s repertoire. Cornwall, in southwestern England, 250 miles from London with next stop America—and about as far off the grid as you can get—became an unlikely but artistically fertile hangout for aspirant folk musicians.

Feeding off the artistic miasma centered around the seaside town of St. Ives, Clive Palmer of the Incredible String Band, Michael Chapman, Derek Brimstone, and Ralph McTell all cut their teeth there, lured by the amiable Wizz Jones, a blues guitarist from Croydon, friend of John Renbourn, and a member of a small beatnik community much despised by the locals.

McTell would find fame and fortune with “The Streets of London,” but unlikely as it seems—although there is a clue in his adopted name—he slavishly attempted to copy the ragtime picking of American blues players like Blind Blake, Elizabeth Cotten, and Blind Willie McTell, interspersed with a few Dylan and Woody Guthrie numbers.

Michael Chapman, on the other hand, was always a maverick. McTell showed him dropped-D tuning and remembers him continually breaking strings on his Gibson Country Western and using his wedding ring as a slide. A man whose road kit still consists of “a guitar, a lead, and a packet of sandwiches,” Chapman revels in his use of often unconventional tunings and is arguably one of the most underrated guitarists on the scene. A great example of his unusual approach can be found in the atmospheric “Caddo Lake,” where his extensive use of harmonics on his Larrivée L-05 in D A C G C E tuning produces a moody and mysterious epic.

ADVERTISEMENT

Blues run the game

Meanwhile, 700 miles away in Edinburgh, Scotland, the club called the Howff—a word in Scots dialect meaning a place of secrecy where rogues can meet and plot—was fast gaining an enviable reputation. Visiting Americans Brownie McGhee, Pete Seeger, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe played there, and a young Bert Jansch was a regular. But it wasn’t until 1962, a point at which his guitar playing far surpassed that of any of his Scottish contemporaries, that Jansch began to make his presence felt, hitchhiking to London to play.

After travelling around Europe, Jansch released his eponymously titled first album in 1965. Performed on a Martin 000-28 lent by Martin Carthy and recorded on a Revox reel-to-reel tape deck in the kitchen of a London apartment, the album contained what would become Jansch classics, the stark “Needle of Death” and “Strolling Down the Highway,” alongside the Eastern-influenced “Kasbah,” and, with a nod to Davey Graham, Jansch’s take of “Angie”—note the new spelling!

Over the years, Jansch ducked in and out of music—for a time, he was a farmer—but his influence across the musical spectrum was immense. Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page adapted Jansch’s version of “Black Waterside,” a traditional tune Jansch had learned from the singer Anne Briggs, into the Led Zep instrumental “Black Mountain Side.” And Neil Young named Jansch his favorite guitarist. His choice of guitars in later years, before his 2011 passing, was a Yamaha LL11.

When John Renbourn recorded his self-titled debut, in 1965, he used his Scarth guitar, a dubious English dance-band instrument, on which he would adjust the action by wedging a lollipop stick under the neck. The album was a patchwork of influences, including reworkings of blues classics “Candy Man” and “Motherless Children,” alongside original instrumentals.

In 1966 Renbourn teamed up with Jansch; their album, Bert and John, was a showcase for both guitarists. The virtuosic interplay on Elizabethan-sounding instrumentals, the almost obligatory Indian raga “East Wind,” and a clutch of self-penned numbers were startling and laid the artistic framework for Pentangle, the seminal British folk-rock-jazz band. Around this time both Renbourn and Jansch also met the reclusive American songwriter Jackson C. Frank, whose haunting song “Blues Run the Game” they both performed throughout their careers.

Medieval Folk Meets Modern Jazz

“You’ve got me for a while, so it’s going to be Celtic misery for a long time,” John Renbourn said self-effacingly at one of his last concerts, not long before he died, in 2015. This was typical of a man who paved the way for the British solo-acoustic guitar scene. Although for much of his career Renbourn’s early obsession with tales of medieval England was much in evidence, he was as comfortable with a ragtime blues by Reverend Gary Davis as he was Merle Travis’ “Cannonball Rag,” Charlie Mingus’ “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” or a Celtic dance tune. Certainly Renbourn’s delight in transcribing medieval lute and harp pieces set him apart. Listen to pure jewels like “Lord Willoughby’s Welcome Home” from his 1976 album, The Hermit; “The Earle of Salisbury” (see transcription on page 70), a medieval dance tune by William Byrd on Sir John Alot of Merrie Englandes Musyk Thyng & Ye Grene Knyghte;or Renbourn’s interpretation of “Lord Franklin.”

In terms of gear, Renbourn chopped and changed instruments a lot, but in his later years played an OM-style guitar made by the York-based luthier Ralph Bown, an instrument he likened to a grand piano. Perversely, Renbourn would ask a soundman using a Shure SM57 microphone to take out the bottom end and make his guitar sound “as cheap and nasty as possible.” In his early days Renbourn used light-gauge strings, but later moved to 12s, using a lighter gauge (.021) G string, with sculpted pieces of ping pong balls attached with superglue acting as fingerpicks!

Nick Drake, Richard Thompson, and John Martyn all followed in Renbourn’s wake, but less well known is Nic Jones. A disciple of Martin Carthy, Jones was a master of minor and modal tunings. A great example of Jones’ playing can be found on his revered album Penguin Eggs. He plays “Canadee-I-O”—a traditional song that Bob Dylan also covered—in Bb F Bb F Bb C tuning. In 1982, only a couple years after he recorded the album, Jones sustained horrific injuries in a road accident, leaving him unable to play guitar and robbing the UK folk scene of one of its most talented performers.

ADVERTISEMENT

Another Carthy devotee, the prolific Martin Simpson, has evolved as one of the most talented fingerstyle performers on the current UK scene. Simpson began his career playing traditional English folk, but during a 15-year stay in the U.S. absorbed a hefty dose of American blues. The result is a remarkable synthesis of styles, including slide guitar, jazz, and country that he makes uniquely his own. Listen to his intimate solo album Vagrant Stanzas to see how this whole thing hangs together.

Meanwhile, with younger performers such as Sam Carter, Laura Marling, and Gwenifer Raymond; the Celtic wizardry of Kris Drever from the Orkney Isles; and Clive Carroll, reckoned by many to be the UK’s finest fingerstyle instrumentalist, the acoustic scene is wonderfully vibrant and diverse. Make no mistake—if John Renbourn’s up there watching, he’ll smile when he hears the playing of Clive Carroll. The pair toured over many years, and with Carroll, who has inherited the master’s versatility and technical virtuosity, his spirit lives on.

Julian Piper, who died in September 2019 at the age of 72, was a blues guitarist with the band Junkyard Angels, music journalist, and author of Blues From the Bayou: The Rhythms of Baton Rouge (Pelican Books).

In Memoriam

On our last walk together, by the Clyst Estuary in the southwest of England, my always animated conversation with musician and author Julian Piper fell to the considerable influence of British guitarists on contemporary fingerstyle playing. We agreed that it would make a good story, and I suggested that he pitch the idea to Acoustic Guitar. As the resultant article was being readied for print, Julian’s wife, Cathy, contacted me with the tragic news that he’d died of injuries after a bicycle accident.

Like many postwar progeny, the adolescent Julian was stricken with that familiar combination of guitar fever and blues disease and, to the end of his life, was never far from that gig-worn Stratocaster and equally used Gibson J-45. He had, at the same time, a scholarly understanding of roots music that enabled him to write knowledgeably about its performance and history, as well as an intuitive feel that allowed him to accompany primal forces like swamp rockers Lazy Lester and Tabby Thomas or Chicago harp wizard Carey Bell. His love of music survives him in his son Sam and daughter Lucy, who are both accomplished and creative players.

ADVERTISEMENT

Julian’s birthplace and lifelong home was Topsham, a small town with a long history in Devon, and his “local” was the Bridge Inn. The wood-heated functions room of this centuries-old pub was the venue for a long running series of concerts that Julian organized. The variety of acoustic music styles presented was a reflection of the eclectic tastes of the host, and the introductions often a vehicle for his dry, acerbic humor.

I will remember my friend on long walks by the Devon seaside, waxing eloquent over a pint of Otter at the Bridge or sitting in his cottage over tea and passing that J-45. These recollections will make me sad that he’s gone—and glad that I knew him while he was here.

—Steve James

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2020 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.