How Bossa Nova Made a Mark on Popular Music

A warm tropical breeze. Sand swishing through toes. The rays of the setting sun reflected in the ocean. And yes, maybe a cool adult beverage (or two) in a glass bedecked by a tiny umbrella. For North American listeners, such are the mental images called up by the sound of bossa nova. Because this subtle, sophisticated music born in 1950s Brazil became the center of a brief commercial craze a few years later in the United States, it’s often thought of today as “retro.” But that’s giving it short shrift.

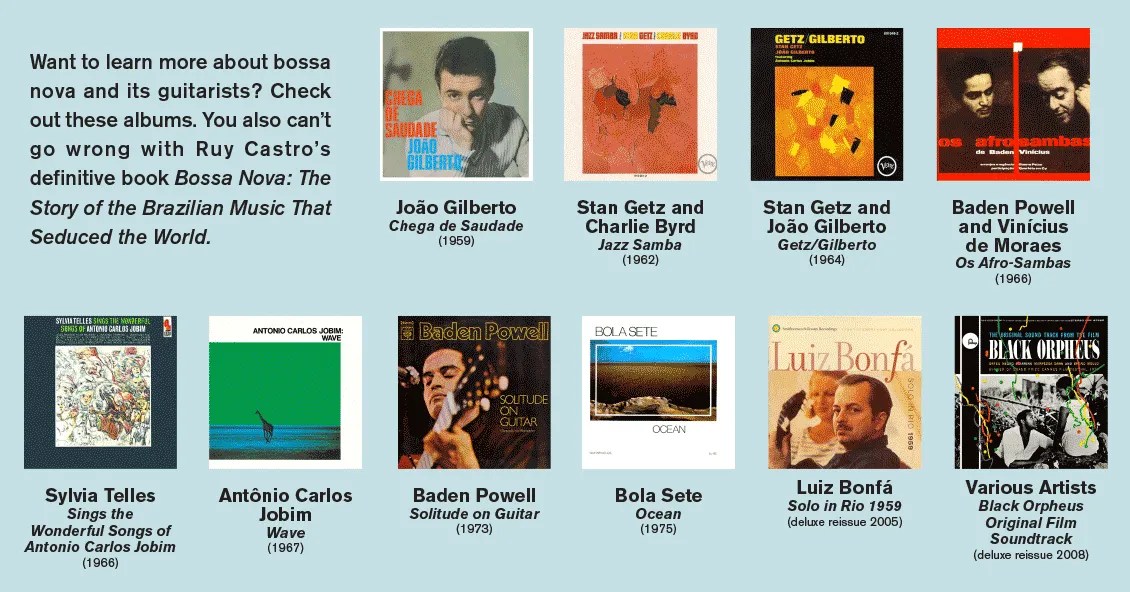

In its home country, bossa was never a fad, and it never really went away. Its distinctive rhythmic syncopation and cool sense of anti-drama have influenced the development of popular music, both in Brazil and elsewhere, for generations. Bossa’s leading exemplars—Antônio Carlos Jobim, Vinícius de Moraes, João Gilberto, Sylvinha Telles, and Luiz Bonfá, to name a few—are now recognized around the world as artistic giants of the 20th century.

Like so many cultural products of the New World, bossa is a true hybrid, blending a rhythm rooted in Africa (the samba) with the complex harmonies of Western classical music and jazz. It’s further distinguished by the unique characteristics of the Portuguese language, with its heavy emphasis on fricative sounds like “zh” and “sh.” And at its core is an old European instrument—the acoustic guitar—conveniently adapted to meet modern South American needs.

A New Thing

The world is full of foundation myths in which great people go into a kind of exile, sequestering themselves from others until they reach a decision, or experience a revelation, that brings them to a new level of awareness. Think of Jesus in the wilderness, or Siddhartha under the Bodhi tree. So it is with the birth of bossa nova as we now know it. The story goes (and is generally accepted by scholars as true, more or less) that over a period of several months in 1956, the singer, songwriter, and guitarist João Gilberto sat in the comfortably echoing confines of his sister’s bathroom in Diamantina, a town in southeastern Brazil, singing quietly to himself and playing a repeating series of chord patterns on his acoustic guitar for hours at a time, day after day. His mission: to create a new approach to performance—which would involve approximating the entire rhythm section of a samba group on one stringed instrument.

Up to this point, Gilberto’s musical career hadn’t worked out so well. He’d shown early promise, moving from his native Bahia to Rio de Janeiro in his late teens to become the lead singer of a vocal quintet called Os Garotos da Lua (the Moon Boys), but had basically kicked himself out of that group due to his own lack of interest. From there he’d drifted for years, seemingly purposeless; his father had even sent him to a mental institution for a short time, frustrated at his son’s inability to find regular work.

ADVERTISEMENT

Its distinctive rhythmic syncopation and cool sense of anti-drama have influenced the development of popular music, both in Brazil and elsewhere, for generations.

But things began to change during an extended trip to the southern city of Porto Alegre, during which Gilberto again began to attract attention as a performer. That prompted his hunkering down in Diamantina, from which he emerged with two innovations: a breathy, nasal, vibrato-free vocal style completely unlike the more conventional samba cancão belting then prevalent in Brazil, and a revolutionary guitar-picking method that separated a swaying bass line from syncopated chords, emphasizing beat 2 and the “and” of 3 in a bar of 4/4.

Returning to Rio, Gilberto soon met up with composer, producer, and arranger Antônio Carlos Jobim (known to his friends as Tom), who was working for the Odeon record company. Impressed by Gilberto’s playing style, Jobim got together with his frequent songwriting collaborator, lyricist Vinícius de Moraes, and came up with a tune that he felt would show off that style to great effect. It was called “Chega de Saudade,” generally translated into English as “No More Blues.” When Gilberto’s recording of the song came out in 1959, Brazilian listeners adored it. “Chega de Saudade” became an enormous hit, and bossa nova was on its way to becoming an international phenomenon.

No one creates something in total isolation, of course. Artists like Jobim, vocalist Sylvinha Telles, and singer/pianist Johnny Alf had independently been working toward something like the bossa nova sound for some time. And the term “bossa nova” had already been applied to music in Brazil; in Portuguese slang, it simply means “new thing.” But what Gilberto was doing really was a new thing, and one of the key elements that made it new was the sound of his guitar.

Changing Strings

Before the mid-1900s, Brazilian guitarists played Spanish-style guitars—built mostly by local luthiers of Italian heritage like DiGiorgio, Giannini, and Del Vecchio—but used steel strings because they were cheaper than gut strings, which had to be imported from Europe. This situation changed after World War II, when Danish-born luthier Albert Augustine (with the assistance of classical guitarist Andrés Segovia and the DuPont corporation) developed the nylon string. Boasting a mellow tone similar to gut strings but more resistant to humidity, easier to keep in tune and, perhaps most important, less expensive, nylon strings were quickly adopted by players in Brazil, including Gilberto. It wasn’t just what he was playing on his DiGiorgio Tarrega that made “Chega de Saudade” sound so novel; it was also the strings he was using.

Gilberto was only one of several Brazilian guitarists during this time who distinguished themselves on the nylon-string acoustic. Among them was Jobim, although he tended to favor piano (despite the guitar being his first instrument). Luiz Bonfá, an exceptional solo player who favored a Giannini model, started out playing samba and jazz but later moved into bossa. His contributions to the soundtrack of Marcel Camus’ movie Black Orpheus—which transplanted an ancient Greek myth to contemporary Rio and won both the Palme d’Or at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival and the 1960 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film—introduced viewers around the world to the “new thing” in Brazilian music. Jobim and Moraes also contributed to Black Orpheus; their “A Felicidade” opened the picture.

Another outstanding guitarist in the early days of bossa nova was Baden Powell de Aquino, generally known by his first two names. A prodigy who was already playing professionally in samba and swing bands by the time he turned 15, Powell made a conscious decision four years later (in 1956) to concentrate on the acoustic guitar and never play electric again—a decision he stuck with for the rest of his life. Powell also struck up a successful songwriting partnership with Moraes, which would result in their classic 1966 joint album Os Afro-Sambas.

ADVERTISEMENT

Bossa Goes International

Many modern jazz musicians in the United States, already fans of Brazilian samba, fell head over heels for bossa nova in the early ’60s. Not only did they love the rhythm, they were also excited by the progressions in many bossa compositions, with lots of major-seventh, minor-seventh, and extended chords that provided rich soil for improvisation. Most assumed that this harmonic complexity was derived from US jazz, but Jobim denied that. “This same harmony already existed in Debussy,” he told arranger Almir Chediak in a 1994 interview. “To say a ninth chord is an American invention is absurd.”

In any case, the admiration between US and Brazilian musicians flowed both ways. And once guitarist Charlie Byrd and saxophonist Stan Getz had reached No. 1 on the Billboard pop albums chart with 1962’s Jazz Samba—which featured compositions by Jobim and Powell, among others—it didn’t take long before bossa artists were regularly joining forces with US jazz players. For example, Powell embarked on a project with flautist Herbie Mann, while Sylvinha (or Sylvia, as her name is commonly Anglicized) Telles recorded with guitarist Barney Kessel. One more immensely talented Brazilian acoustic guitar player, Bola Sete, became a member of pianist Vince Guaraldi’s celebrated trio.

The most famous of these collaborations took place in March 1963, when Getz, Gilberto, and Jobim (on piano) got together at A&R Studios in New York to record an album of eight bossa nova tunes, six of them by Jobim. Released in April ’64, Getz/Gilberto sold more than a million copies and became the first jazz album to win a Grammy for Album of the Year. Its opening track, Jobim and Moraes’ “The Girl from Ipanema,” sung in part by Gilberto’s then-wife Astrud, is arguably still the best-known bossa nova song, and one of the most-covered songs of all time in any genre.

ADVERTISEMENT

At this point, bossa turned into big business. In the hands of pianist/bandleader Sérgio Mendes and others, the music took on a more heavily arranged pop gloss. By the late ’60s, however, a Brazilian reaction to this development was in full swing. The Tropicália movement, led by singer/songwriters Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, and Tom Zé, as well as the band Os Mutantes, stayed resolutely unslick, drawing from both modern rock and traditional folk while maintaining the bossa nova rhythm and the acoustic nylon-string guitar as the major components. Their work has in turn inspired other artists like Vinícius Cantuária and the American singer/guitarist Arto Lindsay, who continue to come up with their own spins on bossa.

Today, many of bossa nova’s originators, including Tom Jobim, Vinícius de Moraes, Johnny Alf, Sylvinha Telles, Luiz Bonfá, and Baden Powell, are long gone. (The 86-year-old Gilberto isn’t, but he rarely performs.) And yet, nearly six decades later, the music they created still has a hold on the world. This was demonstrated memorably during the 2016 Olympics and Paralympics in Rio. Not only did the Games’ opening ceremony include a performance of the “The Girl from Ipanema,” but it also featured two mascots, named Vinícius and Tom.

This article originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.