Island Style: How Hawaiian Music Helped Make the Guitar America’s Instrument

BY MICHAEL WRIGHT

Thanks to the great commercial success of internationally exported, guitar-based American music, many people today think of the guitar as “America’s instrument.” Many also assume—thanks largely to Hollywood—that this has always been so. But the truth is that in Anglo-America, the guitar was a relative latecomer. Depending on which historical window you choose to open, other instruments had much better prospects for that role: banjos after the Civil War, mandolins in the Gay Nineties, and banjos again in the Jazz Age. To understand how guitars ultimately triumphed, it helps to open a different window… onto a group of islands way out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Into the Peaceful Sea

Guitars probably came to the Pacific on Portuguese caravels navigating around Africa during the 15th century; they may also have accompanied Ferdinand Magellan when he claimed the Philippines for Spain in 1521. Spanish missionaries and colonists brought guitars—and guitar making—to the Philippines, where both thrive to this day.

The Hawaiian Islands weren’t “discovered” until 1778, when England’s Captain James Cook dropped anchor and made Hawaii the Pacific’s most important port of call, especially after whaling began in 1812.

Western instruments came with visiting ship crews singing sea shanties and, after 1819, with the growing tide of American missionaries teaching hymns. Whether these crews brought guitars is anyone’s guess, but the Hawaiian people, musically inclined, quickly adopted Western-style music.

Of Cattle and Sugarcane

Legend has guitars coming to Hawaii with Mexican vaqueros from California, who were brought in to round up cattle in 1823. The longhorns had been a gift to King Kamehameha I, who let them roam free, unmolested. Once their sandalwood forests were depleted, Hawaiians turned to beef, hides, and tallow for trade goods.

There’s no hard evidence that the Spanish cowboys had guitars, but Portuguese-speaking sugarcane workers certainly did. Sugarcane was introduced to Hawaii by its original inhabitants, and big sugar plantations had begun by the 1830s. The indigenous population proved to be unreliable cane-field workers, and by the 1850s, plantation owners were recruiting Chinese laborers, followed by Japanese immigrants in the 1860s. Indentured servants from the Portuguese islands of Madeira and Azores arrived to work the fields in 1878. Days after their arrival, Honolulu newspapers were extolling the street-corner musicians among them. The newcomers played the machete or braguinha (mini 4-string guitar) and rajão (5-string guitar with re-entrant tuning), which would quickly fuse to become the distinctively Hawaiian ukulele. In 1879, three Portuguese woodworkers—Augusto Dias, Manuel Nunes, and Jose do Espirito Santo—arrived and soon were producing Hawaiian stringed instruments including ukes and guitars.

Hawaiians did have a native stringed instrument called the ukeke before the arrival of Europeans and Americans. Diplomat and musician Auguste Marques described the ukeke in an 1880s monograph as being shaped like a Greek lyre “made of flexible wood with strings of cocoa fiber.” The similarity between the names “ukeke” and the later “ukulele” is obvious, although could be purely coincidental.

ADVERTISEMENT

Slack-Key and Rusty Bolts

Whichever way guitars made it into Hawaii, by the 1870s, they were popular with native players, who were devising the open tunings and unique fingerpicked style that would become known as Hawaiian slack-key guitar. For American music, however, the major influence came from Hawaiian steel-guitar players.

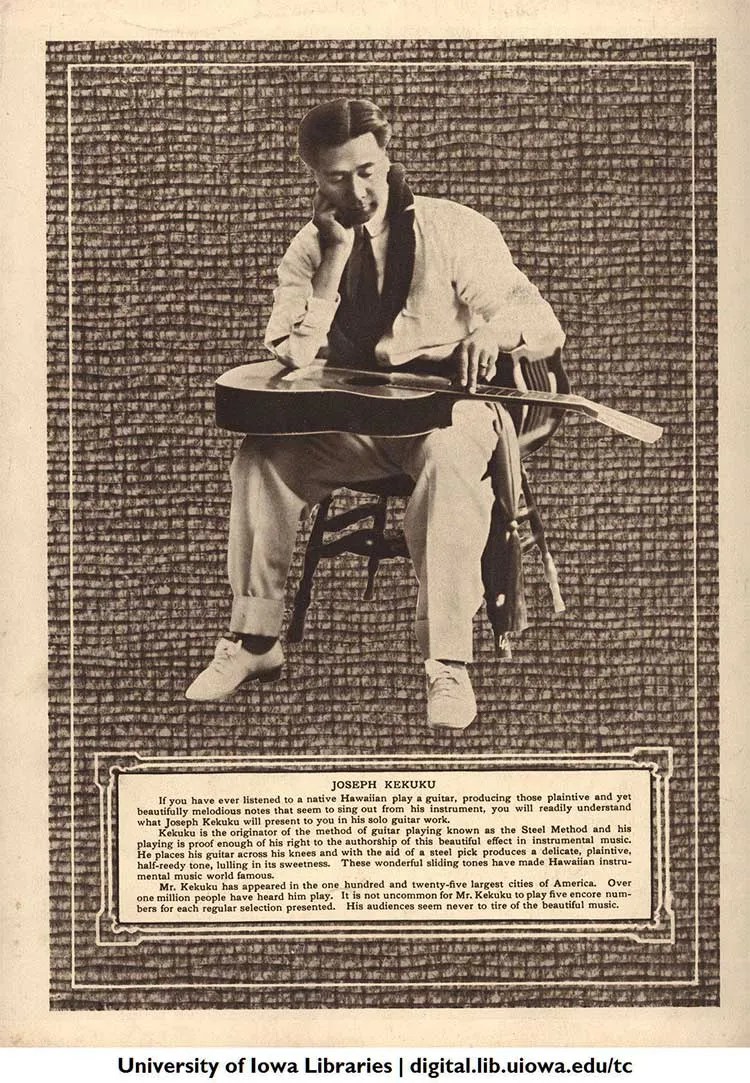

The seminal figure in Hawaiian guitar history is generally conceded to be Joseph Kekuku (1874–1932). According to his own account, in 1889, Kekuku was walking while carrying a guitar and picked up a rusty bolt off the ground. By complete chance, the bolt came in contact with his guitar’s strings, and young Joseph liked the new sound. After experimenting with various other metal objects, including a pocket or table knife and a comb, Kekuku settled on a polished metal bar, and Hawaiian steel guitar (tuned to open A) was born. In 1904, he sailed for the mainland to launch a successful career in vaudeville. Kekuku’s innovative guitar style was immediately adopted by many other young Hawaiian guitar players.

Fun on the Midway

While Hawaiians were playing guitars, the world’s industrial powers were looking for ways to promote their mushrooming economic prowess. In 1851, England erected the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition, the first of more than a century of World’s Fairs, where many nations and industry titans came to flaunt their creations.

More important, World’s Fairs coincided with a growing interest in ethnology and the discovery of both exotic and “primitive” cultures. At the 1893 World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago—alongside the palaces of Machinery, Agriculture, and Art—was the Midway Plaisance, where visitors not only first encountered the Ferris Wheel, but also got to see a panoramic painting of the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii (lava effects created with electric back-lighting), complete with hula dancers and a male vocal quartet accompanied by ukes, guitars, and taropatches (early ukulele cousins with eight strings set in four courses of two strings each). This was the mainland’s first documented encounter with Hawaiian music.

Meanwhile, sugar and pineapple barons were cooking up a coup in Hawaii, and when Princess Liliuokalani acceded to the crown in 1893, the barons deposed her and tried to have Hawaii annexed as a U.S. territory. Unsuccessful, they formed the Hawaiian Republic in 1894. President William McKinley finally created the Territory of Hawaii in 1900.

Hawaiian Music on the Side

This annexation accelerated American interest in Hawaiian music. In 1899, steel guitarist July Paka came with a Hawaiian band to San Francisco to cut the first cylinder recordings for Edison (now lost). Paka married a part-Native American dancer called “Toots,” who got a grass skirt and learned some hula moves. They soon began playing the Orpheum vaudeville circuit as Toots Paka’s Hawaiians, establishing the look and sound of Hawaiian music: lead steel (or Hawaiian) guitar, rhythm Spanish guitar, and ukulele.

In 1901, Columbia released the first recording of “Aloha Oe,” and in 1905-06 Victor sent engineers to Honolulu, where they recorded an astonishing 53 sides, essentially creating the Hawaiian songbook. Hawaiian musicians continued to play the World’s Fairs, including the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (AYP) in Seattle in 1909, which was the first to feature special “Hawaii Days.” Hawaiian guitarist Ernest Ka’ai was hired to provide musicians, among them Pale K. Lua and Kekuku, who stayed on to teach steel guitar in Seattle. One of Kekuku’s students was Los Angeles music dealer and publisher C.S. DeLano, who became the first known mainland Hawaiian guitar teacher and publisher.

‘Hawaiian Guitars‘

Hawaiian steel guitar is played fingerstyle (usually with fingerpicks) on a steel-string Spanish guitar laid flat on the lap. Though preceded by the Portuguese machete and rajão, which also had wire strings, guitars with steel strings became increasingly common in the 1880s. Playing steel guitar requires higher action, obtained with either a taller nut or an extension placed over a regular nut.

The first purpose-built Hawaiian guitars were made by the luthier Chris Knutsen, who likely encountered Hawaiian players at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, in 1905. By the 1909 Seattle AYP, Knutsen was making guitars with hinged necks that allowed players to change the action for Spanish or Hawaiian steel playing. Some non-convertible, hollow-necked, koa-wood versions were made for C.S. DeLano, and these “Kona” guitars became the first mainstream American Hawaiian steel guitars, although most players still used adapted Spanish guitars.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Bird of Paradise

Hawaii-mania reached a new level in 1912, when Richard Walton Tully’s book The Bird of Paradise was adapted into a smash Broadway musical hit that featured Hawaiian music (played on Hawaiian and Spanish guitars), including a version of “Aloha Oe,” and at least one instrumental called “Hawaiian Hula.” The Bird of Paradise toured the country, causing a sensation everywhere; in 1919, it went to Europe, and none other than Kekuku played guitar in it for eight years. The hit tunes were published, and Tin Pan Alley soon began pouring out Hawaiian-themed songs.

By 1914, a national craze for ukuleles had begun, with Martin beginning uke production the following year. By 1916, Herman Weissenborn had taken over making his famous hollow-necked Kona Hawaiian guitars for DeLano. Martin began making Rolando Hawaiian guitars that same year. These guitars continued into the early 1920s, with Shireson Bros. (L.A., Maikai brand) and Oscar Schmidt (Jersey City, Hilo) joining the bandwagon.

The Panama Canal

The most significant event in America’s new fascination with Hawaiian music, however, was the Panama Pacific International Exposition (PPIE), held in San Francisco in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. Nearly 17 million Americans visited from all over the country. At the Hawaiian Pavilion and on Hawaii Days, visitors could encounter the Hawaiian guitar music of Keoki E. K. Awai’s Royal Hawaiian Quartet, Henry Kailimai Quintette Club, Albert Vierra’s Hawaiians, the DeLano Hawaiian Steel Guitar and Ukulele Sextette, Joseph Kekuku, Frank Ferera, and Pale K. Lua. People went home wanting to hear more Hawaiian music.

Following the PPIE, Joseph Kekuku’s Hawaiian Quintet had success working the Chautauqua circuit (basically America’s first summer vacation resorts). Myrtle Stumpf published the first Hawaiian Guitar Method in 1915. And the mighty Sears, Roebuck, and Company bought the Harmony Company, chiefly for their ability to produce Supertone ukes and Hawaiian guitars.

The Teachers’ Association

The increasing interest in Hawaiian music and instruments created a demand for instruction. Conservatories offering group music lessons for children of the growing middle classes appeared at the end of the 19th century. The Chicago Correspondence School of Music was offering mail-order lessons by 1898, and after Heanon Slingerland, one of its teachers, purchased the school in 1914, he began offering a free instrument to customers who purchased a specified number of lessons. Three years later, customers who ordered lessons got a free ukulele, Hawaiian guitar, or banjo produced in a Slingerland factory.

By the early 1920s, selling lessons with instruments had become pretty well established around the country. Perhaps the most influential purveyor of Hawaiian guitar lessons and instruments was Oahu, founded in Flint, Michigan, by Harry Stanley and George Bronson in 1926. Larger cities had active music-teaching organizations, such as the American Hawaiian Teachers in Los Angeles, who recruited students and either rented or sold instruments.

Hawaii on the Air

Another important innovation that would further America’s love affair with Hawaiian guitar music was radio. After Westinghouse’s KDKA in Pittsburgh began widespread commercial broadcasting in 1920, radio caught on like wildfire, essentially becoming an extension of vaudeville, featuring all the top acts, including musicians playing Hawaiian steel and Spanish guitar. One of these was the legendary Sol Hoopii, who began broadcasting live over KHJ radio in Los Angeles in 1923.

Many other technological advances quickly followed, including the 1926 performance of Roy Smeck playing a Stathopoulo Bros. (Epiphone) 8-string Octa-Chorda (a predecessor of the pedal-steel guitar) in the Warner Bros. Vita-Phone film His Pastimes, considered by many to be the first “talking picture.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Jazz and the Tenor Banjo

One of the attractions of Hawaiian music was that its uptempo rhythms had a lot in common with New Orleans-style jazz, another popular music emerging at the time. The driving forces behind jazz were horns and the tenor banjo, with its bright, percussive attack and rapid decay, which were perfect for a fast, cut-time (2/2) beat. Tenor banjos dominated stringed instrument manufacturing during the heyday of the classic jazz band, roughly from the beginning of World War I to the mid-1920s.

But American tastes were changing. Dance-band leaders were demanding more “showmanship” from their musicians. A tenor banjoist who could double on guitar or ukulele became more valuable. In 1925, Regal Guitars head Frank Kordick responded by introducing the tenor guitar, basically a small guitar with a tenor banjo neck, which immediately caught on.

Swinging Country

At the same time, other guitar-based music was becoming popular. Various types of “country” music were emerging from Appalachian folk traditions. In 1924, Chicago’s WLS debuted the National Barn Dance radio broadcast. Dance music had begun a slow shift from syncopated, ragtime-influenced jazz to a less insistent, smoother rhythm that would become “swing” in the 1930s. The new music was more suited to the mellower, woody sounds of a guitar than the clang of the tenor banjo.

According to contemporary trade press accounts, the peak year for tenor banjo production was 1926, followed by a sharp decline. By 1930, guitar production had surpassed that of banjos. After that, guitars never looked back.

The Electric Revolution

With electricity now powering radio, recording, and the talkies, it was only a matter of time before it would get harnessed for guitars. In 1924, John Dopyera filed for a patent on an all-metal tenor banjo with a sympathetic spun-aluminum resonator cone. In 1925, vaudeville promoter George Beauchamp approached Dopyera about building him a louder Hawaiian guitar, and Dopyera pulled out his banjo idea, leading to the first National Tricone guitar in 1926. Two years later, both the Vega Company and Stromberg-Voisinet (later Kay) introduced the first electric guitars, both acoustics equipped with transducer pickups. Both disappeared so fast that no examples have yet been found.

But the whole picture changed in 1931 when Beauchamp, now an executive with the National String Instrument Corporation, brought the concept of an electromagnetic pickup to his board of directors. When they declined, Beauchamp promptly joined Adolph Rickenbacker, who made National’s metal guitar bodies, to form Ro-Pat-In. In 1932, they introduced the world’s first successful electric guitar, the Elektro A-25 Hawaiian electric lap steel, the cast-aluminum “frying pan.” The new instrument was immediately embraced by Hawaiian steel players, including Alvino Rey, who was broadcast playing one later that year. In early 1933, Joseph Lopez (with Noi Lane’s Hawaiian Orchestra) made the first electric guitar recording using an A-25 on sides cut for RCA. The new electric lap-steels were quickly playing key roles in music as diverse the Hawaiian swing of Lani McIntire and his Hawai’ians (who recorded with Bing Crosby) and the Western swing of Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, firmly establishing the electric guitar as a legitimate instrument.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Old Redhead and Tiny Umbrellas

Ironically, American infatuation with Hawaiian music came to an abrupt end on December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. After World War II—except for a brief rage for ukuleles inspired by Arthur Godfrey in the early 1950s, as well as the slightly embarrassing fad of tiki bars playing Don Ho records—Hawaiian music largely hibernated until the rediscovery of slack-key guitarists in the mid-1970s sparked the modern revival. Nevertheless, for nearly half a century, the music of Hawaii fueled America’s interest in playing guitars, culminating in the invention of the electric guitar and solidifying the guitar as America’s instrument in the minds of the world.

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.