Remembering Tony Rice: Béla Fleck, Richard Hoover, David Grisman, Chris Eldridge, and Bryn Davies Reflect on Rice’s Life and Legacy

When I was a kid in the mid-2000s, my dad, Jack Tuttle, took me to Hardly Strictly Bluegrass in San Francisco to see my guitar hero. We got there hours early on a foggy day and wove our way through the massive crowd that gathered yearly for the free music festival. We squeezed onto a friend’s picnic blanket by the front of the stage just in time to see a tall man in an elegant black suit walking out holding a dreadnought.

A hush came over the crowd waiting for Tony Rice to strum his first chord. As we watched him through the fog, the thing that struck me the most was the crystal-clear tone he got out of his guitar. He stood completely still on stage and had a mysterious presence that drew me in and had me hanging on every note he played. The mystery of Rice has stuck with me after all these years. I’ve spent hours learning his licks and solos note for note, but have never been able to replicate the sparkling tone that I heard that day in Golden Gate Park.

Having never met Rice, I’ve often wondered about the person who inspired me and so many others to pursue the guitar. I was holding out hope that he would perform again in his lifetime after years without a public appearance, and that I’d get to meet him someday. Hearing the news that Rice passed away on Christmas Day at the age of 69 was heartwrenching for those of us whose lives were forever changed by his music.

Rice first came to prominence with the bluegrass band J.D. Crowe & the New South in the early 1970s. Throughout his four-decade career, he redefined bluegrass guitar playing and left a lasting imprint on the genre. He was a perfectionist who meticulously crafted a style that was all his own, but at times preferred spontaneity to rehearsals and soundchecks. Above all, he was someone who had a deep love for music and understood the importance of sharing beauty with the world.

Rice was also an incredible singer, celebrated for the warmth and clarity of his split-tenor voice. But for the last 25 years of his life, he was unable to sing, due to muscle-tension dysphonia—a disorder that contracts the muscles around the vocal cords—and his speaking voice became strained as well. Rice also gradually developed arthritis in both hands, which made it at first difficult and then impossible to achieve his legendary tone, speed, and accuracy. The last time he played guitar in public was at his 2013 induction to the International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame.

It was a privilege to talk with five of Rice’s friends and collaborators about his music, life, and legacy: Béla Fleck, who hired Rice to play guitar on some of his groundbreaking solo records; mandolin legend David Grisman, who worked closely with Rice for years to create a new style dubbed “dawg music”; Richard Hoover of Santa Cruz Guitar Company, who made the Tony Rice signature model guitar and developed a deep, lifelong friendship with him; Chris “Critter” Eldridge of Punch Brothers, who studied under Rice and gained philosophical and musical insight from his mentor and hero; and bass phenom Bryn Davies, who toured with Rice in the later part of his career.

Throughout these five conversations you’ll hear Rice described as a friend, mentor, collaborator, bandleader, hero, and musical icon. Each interview offers a different perspective, but they all paint a picture of a man who could leave a powerful impression with just a few words, who could be intensely private yet had a rare ability to share a deep part of his spirit through music. Whether you are just discovering Rice’s music or have loved it for years, I hope you enjoy these stories and reflections on his life and legacy.

Béla Fleck

“At the center of so much great music”

What kind of impression did Tony Rice make when you first encountered him?

Well, he was a big presence, so everybody in the bluegrass world was pretty excited about Tony when I came on the scene. The top cats were in the New South when he was in the band. And that was the big thing that was going on in bluegrass when I was coming up. Tony was at the center of so much great music. And then he got into the Grisman Quintet and they showed a way that you could actually make an impact outside of the bluegrass world as well with these [traditional bluegrass] instruments and with that kind of ability.

It was another great example of just being part of great music. I think that’s the thing about Tony that’s impacted my own call as a musician. It’s not just about what you can do to show off your stuff or your tunes—you have to find a way to be a part of great music. And Tony would do that over and over again. Anything he touched would improve and gain a certain validity. It would solidify into a more powerful version of what it was trying to be if he got involved.

So anytime Tony did anything with me he would lend that to my music, and it was addictive because you could play better when he was around. And it was scary, because you weren’t going to do a lot of takes and you really wanted to impress him. He wasn’t sitting around being dark on people or anything. He was always very positive, but you still knew who he was and what he brought. It was intimidating, but that also brought out your best.

What was Tony’s process like in the studio? I’ve heard that he wasn’t super into rehearsing beforehand.

He preferred to just fly and roll and go. And I think maybe earlier in his career, he was more into working out the fiddle tunes note by note. Because nobody could do that with the authority that he could, and the sound and the tone and all that stuff. He wasn’t really into doing that for a session, but he brought the magic.

The thing is, he would do a bunch of stuff that you didn’t ask him to do. [Mandolinist] Sam Bush would be always like, “Hey Tony, you’re not supposed to play there. Your solo is later.” And I’d be like, “Sam, don’t say that. That was so cool. He just came in out of nowhere and added this whole other thing underneath someone else’s thing.” Something would just come over Tony. And so when I was editing the stuff together, I would always look for the places where he did something. It was fun being the guy to choose the takes and parts of takes and finding the magic—and using those parts, because Tony was very spontaneous.

He was never very self-critical in the studio, and he never wanted to do anything again, but now I’m glad I pushed him, as I think we got better stuff because of it. I asked him to overdub solos at times, and he would do one and the guitar would go back into case. He’d slam the case shut and lock it. I’d come back out and say, “Tony, would you mind doing just one more?” And then he’d go, “Yeah, Béla.” And he would open up the case and slowly pull it out, put the guitar back on, and say, “OK, go.”

Describe Tony’s rhythm playing and the effect it had on you as a band mate.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tony had this magical quality, even when he was singing and would just hit a little strum in between [vocal phrases], like on “Home From the Forest.” That was the thing you waited for, just to hear that little punctuation from this guitar; it was so powerful. Tony was at center of it. He could just control a band like nobody’s business.

In an interview in Still Inside: The Tony Rice Story, you talked about recording Cold on the Shoulder and how everything just locked in. What was that like?

I remember that feeling. I was listening to Tony like a hawk, and I don’t know if he was listening to me or just doing his thing. But it was so easy to lock into his guitar part and play the banjo rolls. I felt like we turned into one person.

And that session was really profound for me because I had never felt like that. That was my first real session with Tony and Sam [Bush] together. To me, the Tony-and-Sam combo was just… Tony had this magic X factor, and Sam locked it down in such a beautiful way. Tony was certainly the more spontaneous musician, but leaning against Sam put Tony’s stuff into stark relief. It was very, very special.

Richard Hoover

Building a different tool

What was your impression when you first heard Tony Rice play guitar in the late ’70s?

Tony was really respectful and aloof at the same time, and he struck me as being a Southern gentleman, even though it turns out he started out as a Southern California boy. He had a presence about him of somebody that was important, and I don’t mean that as self-important. He struck me as like, “Oh, I need to get to know more about this guy, because maybe there’s more to him than I realize.”

Then of course, I was immediately impressed with hearing him play. And Tony’s hands spoke of decades. He was born within two weeks of me, so he was like 25 at that time. But his hands showed literally decades of guitar playing; his fingertips were kind of mushroomed, his nails were receded, and you could tell he played guitar all day, every day, for years and years. What really struck me was the fluidity and naturalness of his playing; Tony wasn’t at all mechanical. His phrasing was impressive, but his movement on the guitar spoke of being one with the instrument. I was thinking, “This guy’s going to go someplace.”

You then worked on a signature guitar with Tony. What was that process like?

Tony had an old Martin. That’s such an iconic instrument that I probably wouldn’t even work on it today. But back then it was a really worked old Martin guitar. It was pretty filthy. It had a lot of cigarette ashes in the interior of it, it was kind of stinky, and it’d been modified considerably. And Tony explained that his old Martin had an awesome presence in the Grisman Quintet, but he had to play really close to the bridge to bring out the tone, clarity, and presence of the lead lines that he wanted. That was actually a shortcoming for him.

Also, Tony’s Martin had belonged to Clarence White, and he venerated it. Clarence was his idol. And Tony really worried about it going on the road, because it was old and fragile. So he was looking for a guitar that would have additional features that would make it more contemporary for him, a different tool in his toolbox. With that explanation, we proceeded to make him the first prototype.

We built Tony a dreadnought that was more balanced, like an OM, and that meant that it had a nice bass presence, but it wasn’t boomy like old prewar dreadnoughts can be. We altered the bracing pattern, did some other variations, and presented him with a guitar that we thought was perfect for what he wanted. He came down and played it, and we took a million pictures, which are lost to history.

And it’s funny, he said, “You know, man, I got a cold and I really can’t hear this the way I’d like, so I’ll take it home and I’ll get back to you.” He gave us a call a little later and said, “You know what? It’s not… well, why don’t you come on up and I’ll show you.” So we went to his house and sat and listened to him play and he explained that it had the clarity he was after, but it didn’t have the warmth and the depth of what he was used to in his old dreadnought, and would we give it another shot. We changed the tone of it by using a cedar top, which gave a warmer, older sound right away, and we boosted the bass a little bit. And that one was a hit.

How would you describe your relationship with Tony?

Tony and I both had a lot of similar experiences growing up, and we had a lot of the same challenges as adults. And that commonality was the basis of our friendship—not music, not guitar playing, just the common journey and overcoming challenges.

I won’t go into anecdotal detail, but I’ll tell you that a lot of our friendship dealt with relationship challenges, spirituality, trying to get right with a higher power, and translating that into your dealings with other people. And for Tony, his relationships directly with people were difficult, because he had a celebrity facade and it became more and more who he was over time. It was difficult for him to let his guard down in that regard.

That’s one of the things that I enjoy in my perspective, because I could just be a regular friend and not somebody that he had to impress or worry about me saying something. So that’s why I’m still so guarded today about Tony, because he trusted me all along that we were just talking to each other and not the public.

You wrote [for Bluegrass Today], “It hadn’t crossed his mind that someone might love him without his guitar.” Talk about how Tony coped with the loss of his voice and his guitar chops. I feel like that goes into a broader topic of self-worth and mental health for musicians.

That I think was the beginning of him isolating a bit and staying out of situations where he would be called upon to have one-on-one conversations or that kind of thing. The guitar stuff of course doesn’t happen overnight—it happened a bit at a time—and that was the anguishing thing for him. When we first started to discuss this, it wasn’t something he wanted anybody to have a hint of, that he was having difficulty with stamina, with speed and accuracy. He said, “My fans deserve my best, and if I can’t give them my best I’m not going to do it.” And watching that happen by degrees was hard.

Do you have any later memories of Tony or anything else you’d like to share?

His voice was incredible, as you know, but losing his voice was not the heartbreak it would’ve been if he didn’t have the guitar chops, which he maintained for many years. For a while he could sing or talk for a bit and his voice would cramp up, and it got worse and worse. So here’s a guy that probably had a little bit of a nervousness about speaking to people in a social and relationship context and now is handicapped by not being able to talk very well.

I’m just going to close with my gratitude toward the relationship. A lot of people found it difficult to be friends with Tony. Also, people thought he was stuck-up, egotistical, but that’s an assumption. It wasn’t based on his actions as much as his inaction, the fact that he did not engage with people warmly. He was afraid. Our defenses sometimes make it seem like we are buttheads when we’re just trying to protect ourselves from hurt.

David Grisman

“A complete musician of the highest caliber”

You played with both Tony Rice and Clarence White. Could you describe some of the differences and similarities between the two players?

Clarence had a very unique approach to time in both his lead and rhythm playing. We spent hours jamming in my apartment after playing every night at the Gaslight Cafe in Greenwich Village during a weeklong engagement in 1964 with the Kentucky Colonels that I was lucky enough to have been hired for. When he died I thought I’d never hear that again. When I first played with Tony, sitting on a living room floor in Washington, D.C., having just met him on [banjoist] Bill Keith’s project, my first thought was Clarence is back! I really hadn’t heard Tony until that moment, but it was lifechanging for sure. He had a very similar approach but a more powerful sound. In some ways I’d say that Tony took up where Clarence left off.

ADVERTISEMENT

What was Tony like as a collaborator when you were crafting the sound for The David Grisman Quintet album?

I was already working on arranging my tunes with Todd Phillips on mandolin; violinist Darol Anger; and Joe Carroll, the bassist who played in the Great American Music Band, which I had formed with Richard Greene—a guitarless quartet. When Tony arrived to play with us for a few days before leaving for Japan with J.D. Crowe’s group, he instantly completed the sound, and in a huge way! These guys were all enthusiastically willing participants in this acoustic musical experiment, and I am forever thankful to all of them for helping me realize this vision. Tony, of course, was already a complete musician of the highest caliber, and we all realized that and respected his awesome talent.

Would you say Tony was the realization of a sound you had already imagined, or was it something of a revelation?

Tony’s extraordinary playing certainly made our sound even more unique, and his rhythmic approach to my music immediately gave it incredible strength and richness. It was truly a labor of love, and we rehearsed nearly daily for three months until we played our first gig in Bolinas, California, in January of 1976. Tony was an ideal band member and although I would have loved to have incorporated his singing and bluegrass repertoire into the band, he was adamant in his desire to play “dawg music.” In fact, he named the style!

Since Tony spent significant parts of his life in California, Florida, and North Carolina, would you say the essence of his personality was more West Coaster or more Southerner?

Tony Rice was a unique individual and, in many respects, very enigmatic. I wouldn’t classify him as being from any particular locale, but rather the embodiment of everything that ever influenced him, geographically and culturally. He deeply loved great music, musicians, and sound. Although he was playing in what I consider to be one of the best bluegrass bands of all time when we met, he was listening to modern jazz almost exclusively. T was a gentle, sweet soul who funneled most of his intellectual, emotional, and spiritual pursuits into the music he played. The rest is still inside. His presence has permanently graced my life, and I will always love him and the music he made.

Chris Eldridge

Reflections on a generous and respectful mentor

What about Tony stood out to you and made you want to play guitar like he did? What are your earliest memories of him as a musician and a person?

I really started being just gobsmacked by Tony when I was about 14, after my mom bought me his record Acoustics. But the lightbulb really switched on for me when I saw the Tony Rice Unit at Graves Mountain Lodge, this bluegrass festival in Syria, Virginia, in the Appalachian Mountains. It felt like it was Zeus up there onstage. The whole band was great—they were all these beautiful musicians—but Tony just had this presence, both musically and physically. His head was down, and he was very calm and settled, but also so intense. It didn’t seem like he was fighting anything, so that was also just very striking.

Did you spend a lot of time with him? Did you ever get to jam together?

Once I started getting more serious about acoustic guitar, at a certain point, through pure nepotism, I started sitting in with the Seldom Scene. [Eldridge’s father, Ben Eldridge, was a founding member of the group. —ed.] The Scene used to play every New Year’s Eve at The Birchmere [in Alexandria, VA] with the Tony Rice Unit. I played onstage with Tony when I was probably 16, and he was really nice about it. Even when I was young, he always treated me with respect as a person and as a musician, and that was very meaningful.

Then, when I was in college at Oberlin, I really bonded with him at MerleFest, in 2001, which is where that photograph came from of me and him sitting together on the bed. I was sitting there that night playing his guitar—the Holy Grail of acoustic guitars—and at one point he’s like, “Critter, lean over here with that thing.” He was smoking a cigarette, and ashed it in the soundhole. Swear to God. I was like, “Ah, are you sure you want to be doing that?” He was like, “Yes.” He maintained that it helped with humidity in the spring months.

It goes back to his cultivating a vibe. I feel like even when people talk about that guitar, it has such a strong mystique.

People say it’s not a great guitar, and I think those people don’t know what the hell they’re talking about. It’s the most amazing guitar I think I’ve ever played, and, like you’re saying, there is some vibe that lives around it. I got to take it to a jam session once and play it for a whole evening. I logged some hours with that thing, and it’s an unbelievable instrument. It’s the most responsive acoustic guitar I’ve ever played in my life, bar none, hands down. You can touch it with a feather and you get this beautiful full-range thing. Incredible.

How would you describe its tone and setup?

By the time I started hanging with Tony, he’d started having arthritis, a lot of hand problems, and so the action was set impossibly low. It was literally like a Telecaster, which is why I think a lot of people thought it was a junky guitar, because they would bash on it and it would just buzz and send out this awful sound, like a bunch of tin cans. But Tony really knew how to play it and coax the sound out of it. That was the thing with that guitar: If you played it with that beautiful, delicate, empathetic, sensitive touch, what it had to give is unlike any guitar I’ve ever played.

I used to sit and just play a string on that guitar and just listen to the sound that it would make. It was so beautiful—very direct, but also complex at the same time. There was nothing in the low end that made it feel unwieldy. But it was one of the most difficult guitars I ever played, because it was so responsive. I think Tony really played himself into that guitar and they became as one in this really beautiful way over time.

Talk about the time you spent studying with Tony when you were at Oberlin.

It was totally magical. I was there with my total hero, and he was so generous. He wanted to help me become a great musician. He was very interested in the cultivation of music to share your essence and your soul. Tony loved musicians who were courageous in that way and figured out a way to transmit who they were and what they were about. One of the big things he was trying to impress upon me was that who cares if you’re a great guitar player? That is absolutely not the end of the road; that is just a stepping-stone.

ADVERTISEMENT

The thing that he said that probably has stuck with me more than anything else is, “Look, the whole goal of what we’re doing here is to collaborate with our fellow musicians to make sounds that are pleasing to the ear.” That doesn’t mean that it has to be a bunch of gently strummed major-seventh chords with a bossa-nova beat. It just means that you all are playing towards a common purpose, and you’re listening and trying to make something beautiful happen.

In other words, you’re living for the music, you’re honoring the music, and Tony very much exemplified that better than anyone in our little world, in my opinion. He was able to give that part of himself beyond the amazing technique and the beautiful musicianship. Everybody sounded better when they played with Tony Rice. We all feel those human connection aspects when we listen to his music, whether we’re aware of it or not. That’s my understanding and explanation that I take from Tony as to why he’s the greatest, and the kind of musician that ultimately I aspire to be like. That’s the big lesson.

Bryn Davies

I first started listening to Tony when I was in college at Berklee. The guys who lived in the apartment above me my sophomore year were just insane bluegrass fans and they introduced me to the David Grisman Quintet and the Tony Rice Unit and all that kind of stuff, and I was fascinated. Towards the end of college I met Peter Rowan and started playing with him. I think it was just around a year after I had started playing with Pete, and he was like, “Hey, I’ve been doing some duo stuff with Tony here and there.” And then it eventually turned into the quartet with Sharon Gilchrist on mandolin.

Did Peter and Tony share roles as bandleaders, or was Tony more the leader?

I think Peter was more the leader of that band. Tony definitely took a back seat to what Peter wanted to do, and I think for nothing else other than that he had led his own band for so long and he was just ready to be a worker bee. He loved how different Peter’s songwriting was, and I think people always thought it was such a weird mix because Peter is such a different player than Tony.

And so I think that’s what Tony was attracted to, and also the fact that he could play those Peter Rowan songs and have a completely different outlet than the hard-driving ’grass stuff and the jazzy stuff that he had been in charge of. I really think he was ready to just let people tell him, “Okay, we’re going to play this song now,” and not have to make those decisions on stage.

What was Tony like as a band leader in the Unit versus with Peter?

I feel like at that point in his career, Tony assembled the Unit to be players that he just really felt comfortable with letting do whatever they wanted to do, like [his brother] Wyatt [Rice on guitar] and Rickie [Simpkins on fiddle] had been in the band forever. He would talk a little bit on stage with the Rice Unit about the songs and things and sometimes he would tell little stories and make people laugh.

My last show with Tony was in May 2012, so I played with the Unit for eight or nine years. He was just always really gentle, always very generous, even though he was “Tony Rice.” He was like, “Oh, let’s do this song because Rickie sounds awesome on it.” Or, “Let’s do this duet so that Bryn can do a solo”—even though I was never the kind of technical player that could do bass solos over really fast, crazy stuff.

How would you describe Tony’s personality?

Well, he wasn’t one to just sit there and talk endlessly about nothing; he wasn’t one of the people who would just sit there and tell you their life story at the drop of a hat. Even on days off, his jeans were perfect and he had a belt on and he always wore a collared shirt. I wouldn’t say he was anal, because there wasn’t a pretension about it. He just carried himself very well.

I miss him a lot. When he died, I was so upset. The last time I played with him was about three months before my son was born, and he is eight now. And I was telling my husband, “I can’t believe I’ll never get to play with him again.” Because I always had that in the back of my head: Tony’s going to come back and we’re going to do some awesome show at some fun thing when he feels like he can make an appearance publicly again.

Tony was a really good friend. He was the person I could call at midnight and be like, “Hey, I’m in trouble,” and he’d ask, “What can I do to help?” If you were a friend of Tony’s, he was the most loyal person in the world, and I’ve missed that friendship. I’m really sad that we’ll never get to play together again, but I feel so incredibly blessed that I had a time with him.

ADVERTISEMENT

Photographing Tony Rice

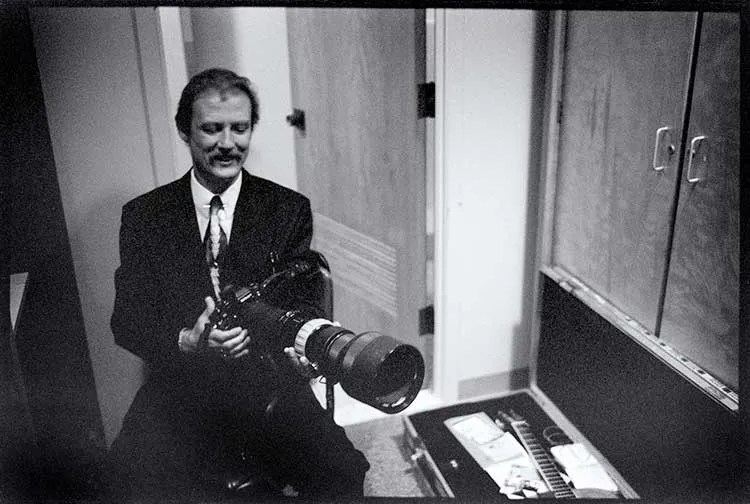

The very first time I photographed Tony Rice was in his dressing room at Wolf Trap, in Vienna, Virginia, during the 1994 Ricky Skaggs Pickin’ Party. As we talked, I was surprised that Rice knew exactly what my 400mm lens was. He asked to see it, so into his hands it went.

Rice had a deep love for photography, lamenting it was hard to find time for it anymore. He collected Canon F-1 cameras and was searching for a rare power cable, which I knew I could find, so he wrote his phone number on a card and said please call him if I do. A few days later, I had the cable and Rice was stoked. From then on we were photo buddies. Whenever we saw each other, we’d talk cameras. I’d always have some new prints for him—he liked to sign and give them to his friends at the show.

Rice was as serious a photographer as anyone else I knew and even shot the cover images for a few of his records. More than once he would hand me his guitar, take one of my cameras, and begin shooting. This photo he took of me is my favorite image, made in his room after a Birchmere show, in Alexandria, Virginia.

What made photographing Rice special to me was how easy the images came. Always dressed for church, he glided around with a conservation of energy; he never looked or acted in a hurry. Going back through my contact sheets reminded me of the calm space he seemed to generate around him. For a while we were in the same orbit, which was cool. He didn’t mind me being around taking photos, and I enjoyed making gallery prints for him in return. I am thankful for all those times. —Jeromie Stephens

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2021 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.

Thank you so much for this beautiful article. The love and respect shown for Tony Rice the man and his music are overwhelming through these shared stories.