4 Contemporary Fingerstyle Masters Reflect on the Impact and Legacy of Guitar Revolutionary Michael Hedges

Andy McKee was 18 when he first encountered Michael Hedges, thanks to a collection of hundreds of guitar magazines that an older cousin gave him. Intrigued by a cover photo of Hedges cradling a harp guitar, McKee, a budding electric player with a love of instrumental music, dug through the stacks of magazines to learn more and came across Guitar Player’s Soundpage recording of Hedges’ “Because It’s There.” With its trance-like tapping, chiming harmonics, and deep bass lines, Hedges’ harp guitar piece sounded more like a trio than a solo performance.

“I was like, this sounds amazing,” recalls McKee. “So I went out and bought all the albums I could find. I got Taproot and Live on the Double Planet, and then Aerial Boundaries shortly after that—and that was what sealed my fate, I guess.”

Built on radical alternate tunings, intricate two-handed tapping, and intense guitar-body percussion, Hedges’ technique was astounding, but the impact of his music went much deeper, McKee says. “I mean, as a guitar player, I was fascinated of course with, ‘What is he doing? How is this one guy?’ But at the same time, I felt such a connection emotionally with his music. He had such a creative and brilliant mind for composition, and he knew how to speak with the guitar.”

McKee never got the chance to hear his new guitar hero in person—just a few months later, in December 1997, Hedges died in a car crash at age 43. But discovering Hedges forever changed McKee’s sense of the creative possibilities of guitar, and he went on to become a top acoustic fingerstylist, continuing on the path that Hedges blazed.

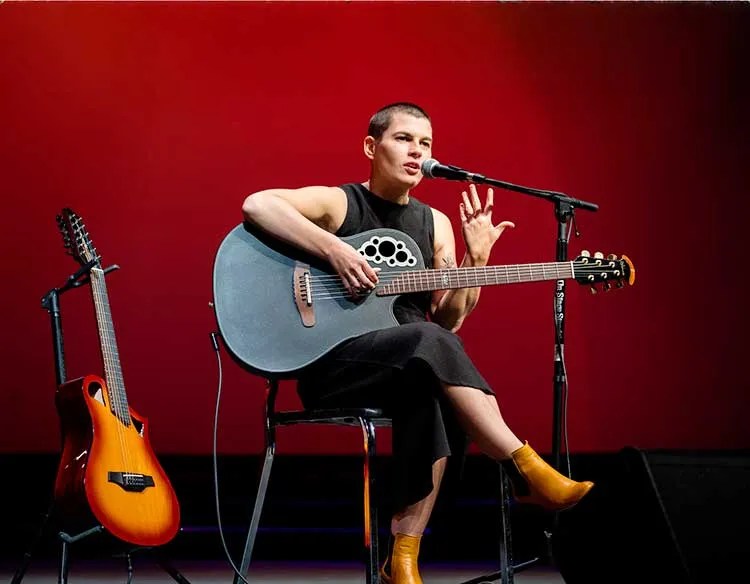

To mark the 25th anniversary of Hedges’ passing, I asked McKee, as well as fellow instrumental guitar masters Kaki King, Christie Lenée, and Mike Dawes, to reflect on how Hedges impacted their lives and music. All have built their careers in the wake of Hedges; McKee and King are in their early 40s, and Lenée and Dawes are in their 30s. These four guitarists have their own distinctive styles but share the sense that Hedges helped make it possible for them and countless other players to do what they do.

“I do feel like I have my own voice, but the techniques and just the inspiration to play the acoustic guitar go straight to Michael Hedges,” says McKee. “And I think anybody in my field that’s being honest would say the same thing, if they’re using weird tunings and unusual techniques on an acoustic guitar. I mean, he blew the doors open.”

Growing Up with Windham Hill

Unlike McKee, Kaki King can’t pinpoint a eureka moment of discovering Michael Hedges, because she hardly recalls a time when she did not know his music.

“I owe so much of my musical education to my father, and he played records all the time,” she recalls. “The Windham Hill catalog was on heavy rotation—Hedges’ Aerial Boundaries in particular, but also Will Ackerman, Michael Manring, Alex de Grassi, Andrew York, and all. And I actually did see Hedges play in Atlanta in a church. I believe I was four or five. My father, again, took me on his adventures. It was just the impressions of a very small child, but I remember Hedges’ hair, I remember his guitar, and I remember him being alone and thinking, wow, how powerful that was.”

All those early memories came back when King began exploring the guitar in a serious way as a young teen in the early ’90s. “When it came time for me to discover those [artists] on my own, I knew where to start,” she says. “I grabbed the CDs, and it was just a matter of listening and going, ‘Oh, I can tune my guitar differently—cool. Oh, I can use all my fingers. I can tap…’ I was really blessed that the music was so readily available.” In addition, King recalls watching Hedges in the Windham Hill Live at Wolf Trap video from 1986 and picking up clues about his tunings and extended techniques.

King never specifically became a disciple of Hedges, as she absorbed a wide range of music. She describes the decade leading up to her 2003 debut album, Everybody Loves You, as “a very slow osmosis of figuring out who I was as a person and as a guitarist.” Along the way, though, the music of Hedges and his Windham Hill compatriots remained a source of inspiration and emotional comfort.

ADVERTISEMENT

“In terms of being a very awkward teenager that didn’t have a lot of other outlets, it was a very safe place for me to go,” she says. “It felt like these core memories of childhood happiness. And I loved being able to write and use that style to fill in where everyone would expect lyrics to go.”

Composing Lessons

Christie Lenée’s first encounter with Hedges’ music came in 2005, when she was studying jazz guitar and composition at the University of South Florida. She hadn’t written much for solo guitar at the time—her main focus was on singer-songwriter material and music for larger ensembles—but she had a commission to write an instrumental piece. On deadline, she felt unsatisfied with her composition thus far and was on the hunt for fresh ideas.

“I ended up going to an open mic and met this guy named Sean Frenette, who is this absolute wizard of a musician and composer,” she recalls. “He got up at the open mic with a three-string guitar, where three strings were removed, and he played this piece called ‘Viennawaterfalls’ that was all tapping. I’d never seen anything like it, and I just was completely glued to him.”

The next day, Lenée met up with Frenette to learn more about tapping—and he told her about Hedges. “Of course I started with Aerial Boundaries, and I couldn’t stop listening to it,” she recalls. “It opened up this whole new world. I listened to it every night as I was falling asleep for probably at least a year, particularly ‘Rickover’s Dream.’”

In composition class, Lenée saw a connection between Hedges’ guitar music and the multipart orchestrations she was studying. “If I was looking at, say, a six-piece ensemble, I had this vision that what Michael was doing was that each string of his guitar became one piece of the ensemble,” she says. “And then he was using a lot of overtones and harmonics, and he’d play percussion at the same time, so it sounds like more than six parts.”

One reason for the sophistication of Hedges’ music, she adds, was his multifaceted background. Hedges played flute, piano, clarinet, and cello, and had a degree from Baltimore’s Peabody Conservatory. At the same time he was studying modern experimental composition, electronic music, and classical guitar at Peabody, he was writing many of the pieces released on his 1981 debut, Breakfast in the Field.

Since discovering Hedges and the world of tapping/percussive guitar, says Lenée, “I’ve heard a lot of people tackle that kind of style, but nobody’s ever done it the way that he did it. And I think that it’s because he was a very trained composer. He was not just a guitar player trying to do fancy stuff. He was using the guitar as a tool to write music, and that’s something I have really taken to heart. I never wanted to just learn his techniques to become flashy or try to copy him.”

Freedom of Expression

Over in England, Mike Dawes found his way to Hedges through his godfather, Allen Greenall, an old friend of French guitar master Pierre Bensusan and graphic designer for Bensusan’s albums and books. As a Christmas present when he was 17, Dawes got the tab book for Bensusan’s 2001 album, Intuite, which included a composition called “So Long Michael.”

“It was my favorite track of the entire album—and obviously it had my name in it,” Dawes says. “I thought, upon listening to it, ‘This is a song I might be able to play if I really try.’ It’s a slower number with some beautiful melodies.”

In the Intuite tab book, Dawes read that “So Long Michael” was dedicated to Michael Hedges. So Dawes did some research and quickly found Aerial Boundaries—on which, in a neat bit of symmetry, track two is titled “Bensusan.”

“Through that, just getting into the Aerial Boundaries record in particular, I fell in love with this whole new way of playing guitar,” he says. “Also, this freedom of composition and expression that’s demonstrated in songs like ‘Spare Change,’ where it’s just playing around with tape loops—that really opened my mind as a teenager and set me on the path of solo expression and self-discovery through the guitar and through music.”

Dawes learned “So Long Michael” from the Bensusan book and started tackling “Aerial Boundaries.” “I was playing it on my Epiphone Les Paul, which as you can imagine sounded awful,” he recalls, “but I couldn’t afford an acoustic guitar.” An accident accelerated his learning: His mother dropped his Les Paul and the headstock broke; they reglued the headstock, and while it was drying, the guitar lay flat on the dining room table.

“I tuned the guitar to DADGAD and spent more time exploring the fretboard from that vertical position and looking at it like a piano, working out where the major and minor arpeggios were and all of this,” he says. “So when I eventually bought my first acoustic guitar, I felt a little bit more proficient in DADGAD than I would have if I just went through learning pieces.”

For Dawes, one of the appeals of Hedges’ and Bensusan’s guitar music was its completeness. “The reason my barometer shifted from electric to acoustic was I can express what I want to express by myself, literally in the moment—bass, harmony, and melody all together,” he says. “When you’re playing electric guitar, you have to be in a band to do that, and I just didn’t have that infrastructure around me where I grew up. Also, I’m very extroverted in some ways as a person—I travel and I socialize—but I’m very introverted in things I create. I don’t want anyone else to have any part. It’s an incredibly personal journey.”

Uncovering Hedges

Several of these guitarists have undertaken the challenge of paying tribute to Hedges onstage and on record.

ADVERTISEMENT

McKee covers “Because It’s There”—his introduction to Hedges—on harp guitar, as well as some of Hedges’ seminal works from Aerial Boundaries. “I’ve had the opportunity to meet his kids and his siblings, and that’s been really great,” McKee says. “They’ll come to a show, and I’ll play ‘Aerial Boundaries’ or ‘Ragamuffin.’ Very, very special moments for me.”

Lately Dawes has been performing an instrumental take on “All Along the Watchtower,” which he introduces as “my version of Michael Hedges’ version of Jimi Hendrix’s version of a Bob Dylan song,” and he plans to include it on his next solo album. Dawes calls Hedges’ rocking interpretation, with vocals, “one of the best covers ever.” With Hedges’ tuning, lowest string to highest, D A E E A A, “You get those unisons, but because the string tensions are different, there is a bit of chorusing. It makes a single guy with an acoustic guitar just sound massive.”

Kaki King had the distinction of playing an exceptionally high-profile cover of Hedges: In the 2007 movie August Rush, she provided the sound and on-camera hands for the actor Freddie Highmore, who starred as a child guitar prodigy, as he performs Hedges’ intense, percussive “Ritual Dance” in a park.

David Crosby recommended King to the filmmakers. “I was really flattered,” she recalls. “But then they were basically telling me to rewrite a song from this worshipped and deceased incredible guitar composer, to make it look better for Hollywood. I really struggled with this one, because I was like, ’This is just sacrilegious.’”

The approach that ultimately worked for King was to imagine Hedges performing “Ritual Dance” (played in the tuning D A D G C C). “I thought, if he was doing this live and riffing, what would he do?” says King. “So that is indeed what I tried to accomplish, and I literally prayed to his spirit: ‘Michael, bud, I’m going to do it. I hope you forgive me.’”

Following the Trail

Oftentimes, as these guitarists have explored Hedges’ music, they’ve been inspired to create their own.

Lenée learned more about the inner workings of Hedges’ music through John Stropes’ transcription book Rhythm, Sonority, Silence. “I’ve found that when I’ve started to learn some tunings,” she says, “I end up getting so inspired by the tunings and the concepts that I end up writing something—just looking at it from the bigger picture of, ‘Oh, OK, I see where he’s coming from.’”

One example is Lenée’s “Breath of Spring,” which she’s recorded for the Acoustic Guitar Sessions video series. “It started with trying to be able to tap one melody on the left hand while playing a countermelody on the right hand,” she says, “so there’s definitely some influence of Michael in that.”

Another idea Lenée gleaned from listening to Hedges is using a tuning with a note other than the root on the sixth string. In “Rickover’s Dream,” for instance, Hedges tunes to C G D G B C, and the song is in G—so the root bass note is on the fifth string, and the bass note of the IV chord is on the bottom. In her instrumental “Chasing Infinity,” Lenée tunes to C G D G A D for a similar effect. “That sound with the low C on the bottom when the song is actually in G, it’s just a really amazing way that a piece can open up,” she says.

Dawes wrote his piece “Encomium (Reverie)” as a direct response to Hedges’ “Dirge,” using the same tuning: B F# C# D A D (in concert, Dawes tunes a whole step higher). Having adjacent strings tuned a half step apart, like the C# and D, he says, “creates these really dark-sounding chords and also scale runs where you can let those notes ring into each other.”

While many guitarists focus on Hedges’ wizardly fingerstyle work, Dawes lately finds himself drawn more to what he calls the “whacka-whacka style”—the hard-rocking strum-based style Hedges used on songs like the above-mentioned “All Along the Watchtower” and “Ritual Dance,” often with unison strings in the tuning. “The whacka-whacka kind of mega Joni Mitchell tunings in the context of an instrumental on a dreadnought is the biggest sound an acoustic guitar can make, and I just adore it so much,” says Dawes. “So that’s definitely an angle I’m leaning towards in my own compositions moving forward.”

ADVERTISEMENT

McKee actually wrote his song “For My Father” while learning “Aerial Boundaries.” He was in the process of getting into the “Aerial Boundaries” tuning, C C D G A D, but had not yet tuned the sixth string down to C. The resulting tuning, E C D G A D, sparked not only “For My Father” but “Rylynn” and other originals.

Beyond Hedges’ specific tunings, McKee says that Hedges—himself inspired by artists such as Joni Mitchell, David Crosby, and Stephen Stills—demonstrated how new tunings can stir compositional ideas. “If you have muscle memory that, here’s the minor pentatonic scale, here’s the major scale, here’s C major, here’s G7, you’re throwing away all those mechanical things,” McKee says. “You’re forced to explore the fretboard all over again like you’re a complete beginner. You don’t know what’s going to be on the seventh fret necessarily. You’ve got a whole new palette to paint with, and you have to try to discover what’s possible.”

The Path to Yourself

Perhaps the deepest lesson—and challenge—from Hedges’ musical path is to buck convention and find your own way. “You have to have people breaking down these boundaries so that other people can walk through them,” says Dawes. “It just so happens that the boundary that he broke through was a really, really thick wall.”

King notes the tremendous growth in the number and diversity of guitarists who’ve walked through that wall and explored all sorts of instrumental music in recent years. “When I started, there was a generation gap, where even the older players were playing to small audiences,” she says. “There was no zeitgeist, no scene, no young excitement, and out of pure chance this became a career for me. But now instrumental music has come back in so many different ways. It is so cool to have people I’m really good friends with that are younger, that are women, that are women of color.”

The guitar world can have “a very sick sense of competition,” King adds. “But the truth of it is, the more of us out there, the more that people know this genre and appreciate it and support it, it’s a rising tide—it floats all boats. So I am thrilled beyond belief.”

Hedges himself, I imagine, would embrace the diversity of sounds and styles in today’s guitar scene—and the way the four guitarists I interviewed are moving in their own directions. That’s evident in their current projects: Dawes has an EP of duets with Tommy Emmanuel coming soon, along with a new solo album; McKee’s next release is ambient instrumental music with all synthesizer—no guitar—to be followed by a guitar trio project with Calum Graham and Trevor Gordon Hall; Lenée is finishing up an album of vocal-oriented acoustic pop-folk with lots of 12-string guitar; and King is scheming to make a collaborative ensemble album.

“I would rather people choose not to imitate me, but to follow what they want,” Hedges told me back in 1990, when I interviewed him at his home studio for the fifth issue of Acoustic Guitar. “I get demo tapes from people who are trying to play like me, but they don’t really work. Nothing works if you try to be like something else. Music is something that you have to say yourself. I don’t want to go to a musical performance where someone says, ‘OK, I’m going to play like Jimi Hendrix,’ just like I don’t go see Elvis impersonators. I don’t see any point in that. But when I hear somebody trying to be themselves, it may not be all that great; but if it’s true, that’s what touches me.

“I’m not saying that people should not learn other people’s material. I play other people’s material. I mean, I once made my living playing Neil Young songs just as Neil Young played them. That’s what I wanted to do at that point, but it was in a process of developing my own thing. I just think that it’s important to be yourself. The path to yourself may be through others.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Documenting Hedges

Fans of Michael Hedges can look forward to two major projects in the pipeline: a feature documentary and a full-length biography.

The documentary, Oracle: The Life and Music of Michael Hedges, is a family affair—directed and produced by Michael’s son Mischa Hedges and brother Brendon Hedges. With a projected release in 2024, Oracle will include archival concert footage, home movies, and extensive interviews with Hedges’ friends and collaborators. Recent filming captured reminiscences from David Crosby and a performance of “Because It’s There” by the 30-member U.S. Guitar Orchestra.

The biography, by guitarist Jake White, should also be published within the next year or two. In the meantime, the revamped michaelhedges.com offers a number of resources for exploring Hedges’ music, including biographical notes, a video library, and even a complete rundown of his stage rig, PA requirements, and string gauges. Also noteworthy is the tuning database now on stropes.com, courtesy of Hedges’ transcriber John Stropes, on which you can find the definitive tunings (and even hear the open string pitches) for many compositions by Hedges as well as Alex de Grassi, Leo Kottke, Andy McKee, and more. —JPR

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2022 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.