5 Ways to Transform an Acoustic Guitar Into Your Songwriting Partner

For a songwriter, the guitar can do much more than accompany your voice and fill in the chords—it can spark ideas and help guide you throughout the process of developing them into complete songs. I look at my Manzer guitar, which I’ve been fortunate enough to play since 1999, as essentially my cowriter. Many of the songs I’ve written over the years began with riffs and grooves I discovered on the Manzer, and I also use it to sketch out possibilities for where ideas may go next.

No matter what guitar you play, it can serve as your songwriting partner. As in any good partnership, the communication goes both ways: You bring ideas to the guitar to try them out, and you also listen to what the guitar has to say. What follows are five ways to use your guitar in the songwriting process, with examples drawn from my experiences in the writing woodshed (scroll to the bottom of this page to view the musical examples).

1. Remake Another Song

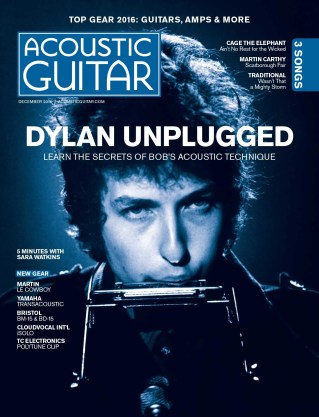

One time-honored method of writing is to learn a favorite song, take a piece of it and change it in some way, and—whether on purpose or by accident—wind up with something new. Some might call this stealing, but it’s really not. Remixing ideas from other songs (or from any other art form) is fundamental to the creative process, no matter how original we perceive the result to be. Just ask Bob Dylan, who has freely used traditional songs, literary quotes, and more throughout his career.

A case in point: I love finding fresh ways to arrange great songs, and on one occasion I did that with the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me.” Instead of the sliding power chords in the original (Ex. 1), I tried it in drop-D tuning, with the capo at the fifth fret, as in Ex. 2—a fun and different way to play those changes that sounds cool on acoustic guitar.

Sometime later I was fooling around with those exact fingerings, slowed down the changes and the tempo, tried a different rhythmic feel, moved the capo down a couple frets, and found Ex. 3. Intoxicated by that groove,

I played it over and over, singing whatever words or sounds popped out until I had the lines, “Almost certain that I’m almost there/Almost across the line.” And with that, I was on my way to a song, “Almost There,” that sounds absolutely nothing like the Kinks song. But “You Really Got Me” is what really got me going.

Something similar happened when I arranged the Grateful Dead’s “Fire on the Mountain” as part of my Homespun video series of Dead songs for acoustic guitar. Looking for a way to bring this song to life, in a key that better suited my voice, I transposed it way down from the Dead’s version, moving between F# and E chords. Ex. 4 shows a sample of the rhythm pattern; fret the E chord with your third, fourth, and second fingers, so you can transition smoothly to and from the F# chord.

ADVERTISEMENT

I don’t typically make an F#-to-E chord move, and it really caught my ear. Eventually I tried a different rhythmic feel with those changes and arrived at Ex. 5—the beginning of a song called “Proof” that, again, sounds nothing like the song that sparked it.

The point is, you can find all sorts of ideas in other songs. Take a chord progression and transform it—speed it up, slow it down, change the rhythm, move to a different key or register, and so on. If you learn to identify chord progressions by Roman numerals rather than letter name—saying, for instance, a progression is I–IV–V instead of G–C–D—you’ll have even more freedom to apply chordal ideas from one song/key to another. (I go into this topic in detail in my AG guide Songwriting Basics for Guitarists, and in the new edition of the book The Complete Singer-Songwriter.)

When you’re working with an existing song, don’t worry too much about stealing. No one owns a chord progression. If you directly quote someone else’s melody or lyrics in your song, you are stealing, but even those elements can be transformed into something new and unrecognizable. Whenever you’re playing around with a piece from another song, keep changing it until you no longer hear in your head what you started with. That suggests you’ve crossed the line from imitation to creation.

2. Follow the Pattern

At their root, songs are all about patterns—they introduce some kind of pattern of melody, harmony, or rhythm and then create variations on it. (The same applies to lyrics as well.) The recurrence of the pattern is what holds the whole thing together. When you’re working on a song, the guitar can help you recognize patterns and develop them.

For instance, with “Almost There,” the rhythm pattern I started with moves between D and C—the root goes down and up a whole step. (I’m actually playing an inversion of a C chord with G in the bass, but the chord still registers as a C.) So for the next move in the progression, it made sense to follow a similar pattern on the IV chord—changing between G and F, as in the second half of Ex. 6. Again, that’s down and up a whole step. Use a first-finger barre on the bass strings for the G and F chords.

As a bonus, when I played this new pattern, the fingerings generated a nice little melodic figure: from the fifth fret on the third string to the open second string, at the end of measure 3. So I used that figure—

suggested by my six-string collaborator, the Manzer—in the vocal melody.

Similarly, my song “I’ve Got It Here Somewhere” began life with the blues-rock riff in the first four bars of Ex. 7. Use a first-finger barre on strings 5 and 4, and keep your fourth finger in place on string 3 throughout. In this pattern, the bass moves from the open sixth string to the third fret and back again. From there I go to the IV chord (A), and alternate the bass from the open fifth string to, once again, the third fret on the sixth string, as in measure 5. With this pattern, I lay out the song’s main harmonic territory.

When you come across a cool pattern on the guitar, take a closer look at what’s happening in the music and try applying or extending the pattern in some way. In writing, it’s always good to build from ideas you’ve established rather than shoehorn in something unrelated.

3. Listen for Melodies

As happened with my earlier example of “Almost There,” the guitar can suggest melodic ideas for the vocal. At times you may even find a complete melody on the fingerboard. In the case of “Somehow,” I sat down with the Manzer and my fingers fell right into the minor-blues melody of Ex 8. This passage had a strong mood of aching and longing, and the guitar melody just called out to be sung. So my job in writing was to find words that matched the feeling and the phrasing just right.

The lyrics in the example show the first verse. In the completed version of “Somehow,” I sing in unison with the guitar melody through almost the entire song, except for a few spots where the vocal and guitar harmonize.

ADVERTISEMENT

Even when you’re working with a melodic idea that you didn’t come up with, the guitar can help you develop it. Find the notes of the vocal melody on the fingerboard; playing the melody and listening without singing may help you figure out how to strengthen it.

Also, notice where your melody falls in relation to the chords. If you’re singing the root note of each chord most or all of the time, try singing a different note in the chord—the third, say, or the fifth, or even a note that’s not in the chord at all—to achieve a more independent melody. (Conversely, you can try playing a different chord and leaving the melody note where it is.) The guitar can help you try out melodic alternatives that may not occur to you as you sing.

4. Let Your Fingers Do the Walking

At times, fresh musical ideas for songs come from pure experimentation on the guitar—simply dropping your fingers on the fretboard and hearing what comes out. That’s how, for instance, I found the chords for the bridge in “I’ve Got It Here Somewhere,” shown in Ex. 9.

I started with the spacey Asus2 chord (as used in the chorus, Ex. 7) and found the rest of the progression by trying different bass notes under the same drone on the upper strings. I had no idea what chords I was playing—I was going purely by sound. And good thing I did, because it led me to that delicious F#7sus4 that I probably wouldn’t have found otherwise.

In fooling around on the guitar, don’t be afraid to try unfamiliar fingerings or leave open strings in chords where they don’t normally go. The worst that can happen is that you play something that sounds bad, so you grimace and move on. At best, you find a tasty and unexpected new ingredient for your song.

5. Detune

Alternate tunings can provide a powerful way to break free of your playing habits and generate ideas. They allow you to create complex chords with simple fingerings, and they can also accomplish the trick of making common chord progressions sound new and unfamiliar. The feeling that you are discovering something—even when you’re using the same basic ingredients as everyone else—is the lifeblood of songwriting.

I don’t use particularly crazy tunings, but I do have a growing number of songs in tunings that drop the bass strings and leave the others in standard (the topic of my Weekly Workout in the June issue). One of these, titled “My Bad,” came to me thanks to the tuning C G D G B E. I happened upon the funky bass line in Ex. 10 and was hooked. No way would this have come to me in standard tuning. The tuning also facilitated the low power chords in Ex. 11, as used in a section of the verse.

ADVERTISEMENT

By the way, you can get into the alternate-tuning zone without actually retuning. Just use a partial capo. Partial capos that cover three and five strings have helped me find several recent songs. “Turn Away,” for instance, has a dead-simple chord progression—mostly I, vi, IV, and V—that wouldn’t have interested me if I’d played it in standard tuning. But I played it with a partial capo on the top five strings plus the sixth string tuned down to D, and the progression intrigued me. It sounded like the beginnings of a song, and now it is one.

Beyond the Guitar

While the guitar is a versatile partner for songwriting, I do recommend getting away from the instrument, too, at some points in the process. Try singing with no accompaniment, or record the guitar part on your phone and sing over it, while driving or walking. Even Richard Thompson, with his astonishing guitar chops, told me a few years ago that he finds it freer sometimes to write away from the instrument, in his imagination.

Writing this way, you can dream up things that you may not know how to play . . . and then you can come back to your faithful six-string and figure out how to make it happen.

ADVERTISEMENT

This article originally appeared in the December 2016 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.

Many of the teachers who contribute lessons to Acoustic Guitar also offer private or group instruction, in-person or virtually. Check out our Acoustic Guitar Teacher Directory to learn more!