How Acoustic Musicians Are Carrying Forward the Songs of the Grateful Dead

In 2014, Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter took the stage at the Newport Folk Festival in what turned out to be one of his last public performances. Fingerpicking a Taylor acoustic-electric, he played songs like “Friend of the Devil,” “Ripple,” and “Brokedown Palace,” while the audience—mostly way too young to have seen the Grateful Dead in person—sang along with every word.

“This being a folk festival, I thought I’d sing some folk songs,” Hunter said. “I wrote them myself but, you know, they’re folk songs.”

It’s now been nearly 30 years since the passing of Hunter’s songwriting partner Jerry Garcia brought the long, strange trip of the original Grateful Dead to a close, and the truth of Hunter’s observation is more apparent than ever. For decades there has been a huge Dead tribute scene, with countless bands devoted to recreating the group’s sound and even specific set lists. But over time, the songs of the Grateful Dead—not only their originals but the jambalaya of roots music they interpreted—have gone deeper into the culture to become a common language, like jazz standards or fiddle tunes. If you include the wide-ranging side projects of Garcia in particular, from his solo albums to the Jerry Garcia Band, Old and in the Way, and his collaborations with mandolin master David Grisman, you have a treasure trove of American music.

These days, even as the surviving band members carry on in various configurations (Dead and Company, Phil Lesh and Friends, Billy and the Kids), all manner of songwriters and instrumentalists are putting their own spins on Grateful Dead music—including an array of acoustic musicians, who are both connecting with the Dead’s own acoustic legacy and creating new acoustic identities for their songs.

I personally have been exploring this realm of acoustic Grateful Dead, teaching Dead songs for acoustic guitar in workshops and a Homespun video series, and performing with my collective Dead to the Core. To dig deeper, I reached out to some musicians creating fresh acoustic interpretations of the Dead’s music: Andy Falco, who celebrates Garcia’s repertoire in a duo with his Infamous Stringdusters bandmate Travis Book; Sam Grisman and Aaron Lipp of the Sam Grisman Project; Paul Kotapish and Sylvia Herold of the long-running Celtic band Wake the Dead; and Grahame Lesh, who digs into Dead music with his father, Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh, as well as the Terrapin Family Band and Midnight North. Here these musicians share thoughts on what the Dead’s songbook means to them, and how they approach it as a living tradition.

Grass Routes—Falco & Book Play Jerry Garcia

A funny thing happened on the way to the Grateful Dead becoming the prototypical jam band: they became a major gateway to bluegrass, thanks especially to Jerry Garcia’s beginnings as a banjo picker and his stint in the ’70s with the short-lived bluegrass band Old and in the Way alongside David Grisman, Peter Rowan, Vassar Clements, and John Kahn.

That’s how Andy Falco, guitarist for the Infamous Stringdusters, found his way to bluegrass. “Old and in the Way turned a lot of people who were into the Grateful Dead, including myself, onto bluegrass music,” Falco says. “And then there were Jerry’s continued collaborations with David Grisman, with Grisman and [Tony] Rice, and even the Garcia Band when he would do the acoustic stuff—that was really a bluegrass band.”

Furthermore, Falco notes (crediting fellow guitarist Scott Law for the observation), even Garcia’s electric style is very banjo-like, with its bright tone and melody focus. “There are the psychedelic jams,” Falco says, “but at the core of it all, a lot of Garcia’s parts and melodies are very much like an approach a bluegrass player would take.”

Garcia’s influence in the bluegrass world runs deep enough that in March the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Kentucky opened a two-year exhibit titled Jerry Garcia: A Bluegrass Journey, with an opening gala that included Garcia’s picking pals Peter Rowan, David Nelson, and Eric Thompson, as well as Sam Grisman Project and the bluegrass/jam veterans Leftover Salmon.

ADVERTISEMENT

Given the extensive connections between the Dead and bluegrass scenes, it’s no surprise that many progressive-leaning bluegrass bands dip into the Dead repertoire. The Infamous Stringdusters are a prime example, dropping bluegrass takes on Dead tunes like “Tennessee Jed,” “Jack Straw,” and “Touch of Grey” into their sets of primarily original songs, along with plenty of Dead-inspired jamming. “As a band, the ’Dusters all have connections, influence wise, to the Grateful Dead,” says Falco. “Part of our musical DNA is the way we approach improvised jams that don’t have a plan.”

In 2018, Falco and Stringdusters’ bassist Travis Book felt inspired to dig deeper into the Dead repertoire, leading to duo tours and a live album under the billing Falco and Book Play Jerry Garcia. They chose to focus on Garcia songs since Bob Weir, the other main contributor to the Dead repertoire, and the rest of the band are still on the circuit. “I love the Weir stuff as well,” Falco says, “but you can go see Weir—he’s still active and doing it great.”

With Falco flatpicking his Bourgeois guitars (he has a dreadnought, OM, and custom Nova) and Book on upright bass, the duo plays not only originally acoustic songs like “Friend of the Devil” and “Ripple” but epic electric ones like “Terrapin Station” or “Help on the Way/Slipknot,” creating the impression of a bigger band by being flexible with their parts.

“Sometimes Travis is playing a role of Phil [Lesh] or John Kahn or whoever the bass player was,” Falco says. “Sometimes he’s playing the role of Weir rhythmically, or even playing some of the lead lines. I might be playing Garcia’s part or a little bit of Weir’s or Grisman’s part. We’re just trying to get whatever hits us as essential for that moment. It’s just a duo, but with an upright bass and guitar and two voices, there is a lot you can do.”

In keeping with the Dead’s ethic, they take an open-ended approach to performance. “We don’t do set lists,” says Falco. “I have a list of all the material we can do, and we just feel the energy of the room and let it guide where the sets go.” The same is true within songs. In the duo’s released live take of “Friend of the Devil,” for instance, at the end of the last chorus you can hear them call an audible to stay on the D, the V chord, drifting into an extended jam that lands eventually on A minor for “Jack-A-Roe”—which itself stretches to seven minutes with some barnburner flatpicking solos and several tempo changes.

For Falco, performing songs like these feels like reconnecting with his roots. “When you’re playing Garcia or Grateful Dead music, it’s often thought of as cover music,” he notes. “But in the bluegrass world, you can be playing Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs, and it’s considered traditional music. It’s interesting because for me, playing Grateful Dead music is like playing traditional music. Those are the songs we were playing around the house when we were kids. It’s part of our musical language.”

The Family Dawg—Sam Grisman Project

When I spoke with Sam Grisman for this article, it wasn’t the first time we’d met: that actually happened back in 1993, when he was three years old. I was in his house in Mill Valley, California, interviewing his father, David Grisman, and Jerry Garcia for AG in the basement studio where they recorded regularly in the last years of Garcia’s life—at the time, their latest release was the charming, folky Not for Kids Only.

“The Not for Kids Only record was actually my mom’s idea,” Sam recalls. “It felt like my dad and Jerry made that record for Jerry’s daughter Keelin and for me and for all of our friends who were around that age.”

Sam was about to start kindergarten when Garcia died, so he never got the chance to make music with his dad’s pal. “But we do have some family home videos of my dad and Jerry playing in the living room,” he says. “I’m running around in diapers and clearly musically inclined—picking up little toy instruments and trying to jam with those guys, and they’re pretty good sports about it. I just grew up hearing that music and wanting to play that music, wanting to be one of the boys.”

Thirty-some years later, he is following that childhood wish with the Sam Grisman Project, a tremendously versatile band with Aaron Lipp (guitar, keyboard, fiddle, banjo), Ric Robertson (guitar, mandolin, keyboard), Chris J. English (drums), and Grisman on bass. All four members sing lead and harmonies, and both Lipp and Robertson are adept on lead and rhythm guitar. The fast-rising band celebrates the Garcia/Grisman repertoire but ranges much more widely, performing songs by the Dead and other artists plus quite a few originals. Their arrangements are full of surprises, too, like a zydeco take on “Easy Wind” or, at a recent show I caught, “China Cat Sunflower” somehow segueing into “Ring of Fire.”

“I think it would be quite a disservice to my dad and Jerry to try to duplicate what they’ve already done, and I love the individuality of all of my friends,” Grisman says. “We’re not a tribute band really. We play lots of original material, and we play tunes that my dad and Jerry didn’t play. A lot of that stuff is Garcia/Hunter music that resonates with us, like ‘Liberty,’ ‘Row Jimmy,’ ‘Ruben and Cherise, ‘It Must Have Been the Roses,’ or any of these great songs that my dad might not even have much awareness of.”

Growing up, Lipp learned many songs from the Old and in the Way record, Not for Kids Only, and the Dead’s Europe ’72 and Workingman’s Dead, but he doesn’t aim to re-create Garcia’s singular style or parts. “Jerry was of course fascinated with Django [Reinhardt] and Oscar [Alemán], but he wasn’t trying to sound like anyone,” says Lipp. “I have certain things in my playing that might resemble Jerry licks, but in no way am I striving to get that sound or tone. That’s part of what keeps the originality alive.”

Along with their expansive repertoire, the Sam Grisman Project performs both fully acoustic and fully electric, switching back and forth by set. “Most of the stuff can be done acoustic or electric,” says Lipp, whose stage guitars include vintage Martins (a 1943 D-28 on loan from David Grisman, and a 1950 00-17), a 1975 Harmony Broadway hollow-body archtop, a 1977 Les Paul for slide, and a K Douglas custom Strat. “And we still get pretty psychedelic with the acoustic stuff. We’re not afraid to take it to outer space.”

Grisman adds, “I feel like our flexibility with being either electric or acoustic really adds a lot to keeping this material fresh for us. And I consider it an awesome challenge and a privilege to play our acoustic sets on an array of condenser microphones, no matter what kind of room we’re in. We don’t use DIs with any of the acoustic instruments we have out on the road, so there ain’t no plugs on us.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In the acoustic sets, Grisman notes, “We’ve really created an atmosphere where people can have a profound shared experience. We’re a part of that as much as the audiences. It’s like going to church with a bunch of strangers who become your family because you all care so much about these songs.”

Celtic Connections—Wake the Dead

One of the most inventive acoustic takes on Grateful Dead music first emerged back in 2000 around a San Francisco Bay Area kitchen table. Paul Kotapish and Danny Carnahan, two trad-oriented multi-instrumentalists (and AG contributors), teamed up with the notion of arranging Dead songs in a traditional folk style, and they tried it out initially with Kotapish on mandolin, Carnahan on octave mandolin, and Maureen Brennan on Celtic harp.

All three had deep knowledge of Celtic traditional tunes, which Kotapish started weaving into Dead songs. “When it came time for the break, I just would launch into tunes because I knew they knew them,” Kotapish recalls. “That became the language we developed for working these songs up.”

With this MO, they wound up with arrangements like “Banks of Lough Gowna/The Reunion/Friend of the Devil,” which opens with two Irish 6/8 jigs, lands in 4/4 for “Friend of the Devil,” and returns to the jigs in the instrumental breaks. This unexpected combination works brilliantly, shedding an entirely new light on the Dead originals.

“You know, the particular Celtic thing is a little more obscure,” Kotapish says of their approach. “But so much of the American traditional music that was the Dead’s bedrock is that fusion of Irish/Scottish/English with African music, so to me, there’s a continuity and logic.”

With a dozen braided arrangements, such as “Coleman’s Cross/Bird Song” and “Lord Inchiquin/Sugaree,” the group initially planned only to make an album for limited release, with the addition of upright bass, fiddle, whistle, uilleann pipes, and percussion. But then Carnahan sent the mixes to the Grateful Dead office, where the remaining band members heard this fresh take on their music and offered to release it on Grateful Dead Records. And with that development, Wake the Dead became a performing band—and they’re still at it, with four albums out and a repertoire that later expanded to include other contemporaries of the Dead.

Though both play guitar as well, Kotapish and Carnahan still focus on mandolin and octave mandolin, respectively, in Wake the Dead. Sylvia Herold, initially brought in as a harmony singer, eventually added her rhythm guitar to the mix. Herold had no real background in Dead music but was steeped in swing and Irish music, and the latter in particular proved relevant to the Dead project. “I developed a style of playing that is based on a lot of power chords—sliding chords that don’t have thirds in them, primal-sounding chords,” she says. “That has been really helpful in my guitar work with Wake the Dead.”

To complement the mandolins, Herold uses a lot of partial chord voicings up the neck, often with open strings, playing a Martin-esque flattop built by Frank Ford and Richard Johnston in the early days of Gryphon Stringed Instruments (see the May/June issue for a tribute to Ford). “It’s using the guitar to its full potential when you can drone on some open strings,” she says. “That’s allowing the box to vibrate in the way it was meant by God to do.”

For Kotapish, one of the core reasons why Wake the Dead’s unusual fusion works so well is the nature of the songs—especially the Garcia/Hunter repertoire. “I think in much the same way that Robbie Robertson did, they were tapping into this timeless approach to songwriting,” Kotapish says. “In my mind, the songs weren’t tied to a specific moment.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Unbroken Chains—Grahame Lesh

Growing up in the Grateful Dead family, Grahame Lesh had Dead songs embedded in his earliest musical experiences. His first memory of playing guitar as a kid is of his dad showing him and his brother the two chords for “Franklin’s Tower.” In high school, he says, “The first time I played a talent show with some buddies, my dad was nice enough to play with us, and we did ‘Sugar Magnolia.’ That was my real introduction to learning a full song.”

Lesh says his favorite Dead music comes from the band’s more acoustic era, when they laid down the back-to-back masterpieces American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead. He also feels a special connection to his father’s infrequent but memorable songwriting contributions, like the quirky, country-flavored“Pride of Cucamonga” and the harmonically and metrically complex “Unbroken Chain.” As a six- or seven-year-old listening to “Unbroken Chain,” Grahame questioned why the Dead never performed the song. “I had no conception of how convoluted it was musically, in the best way,” he says. “I was definitely the one who put the bug in my dad’s ear: ‘Well, why haven’t you played it?’ They finally played it in the last years of the Grateful Dead. Now we play it all the time. Phil and Friends plays it quite often.”

For Grahame’s own musical development, a pivotal experience came in 2012 when his parents opened Terrapin Crossroads, a Bay Area venue inspired by Levon Helm’s Midnight Ramble in Woodstock, New York. “I was one of many musicians on call to be available to play on, say, a Tuesday night with a random collection of our friends,” he recalls. “That was where the repertoire really built up for me, and my band Midnight North was starting at the same time. I dove into not just the Grateful Dead but the Beatles, the Stones, Dylan, the Band, and the Deep Dark Woods and Brandi Carlile and modern stuff, too. That was real musical boot camp in an awesome way.”

Though the venue closed during the pandemic, Lesh still performs with the Terrapin Family Band occasionally, in addition to playing with Phil Lesh and Friends and with Midnight North, all on both electric and acoustic guitar. His acoustic of choice is a Martin HD-28. “With my band, we play a lot of our original music,” he says. “When we do a Grateful Dead cover, we do try to switch it up and give it our own spin. But some of it is so [naturally] in the key that it’s in, and with the feel that it has, that it’s really hard to give it something unique without changing something inherent.”

A recent session for eTown in Colorado captured a Lesh father/son duo set, with Grahame fluidly mixing rhythm and lead on acoustic guitar over Phil’s idiosyncratic bass lines. “Anytime I play with my dad, he’s such unique bass player that it’s going to be a unique scenario,” Grahame says. “If it’s just going to be the two of us, I prefer an acoustic guitar because you can be the drums and the rhythm guitar all at the same time. The way my dad likes playing with drummers is also unique, so that affects how my right hand goes.”

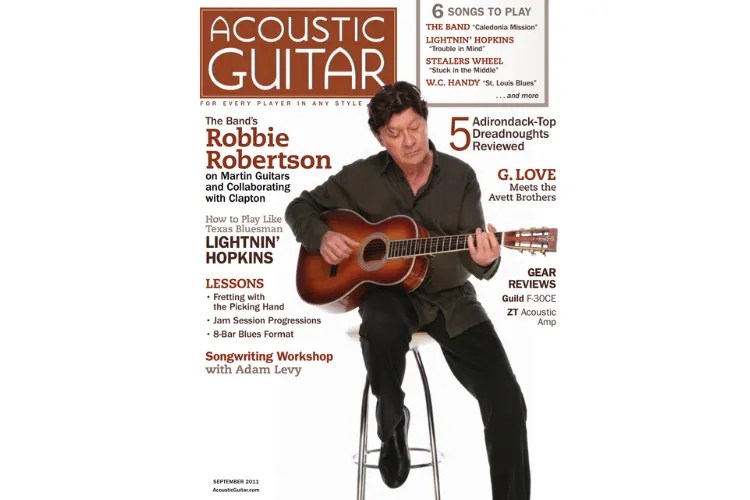

Lesh notes that the acoustic guitar connects deeply to the Dead’s songwriting. “I find that all these Grateful Dead songs, especially Jerry songs, are just laid out on guitar in such an intuitive way,” he says. “There’s something about the way that the chords move, you can kind of picture the next chord even if you don’t know the song all that well—like if you’re going from G to E major, that chromatic walkdown. It’s very much a thing that someone writing on an acoustic guitar would do. So I think about Garcia on acoustic guitar, probably the Martin [a 1943 D-28; see AG September/October 2021], writing these things. It’s almost like the guitar is telling you where to go.”

Songs of Our Own

In these conversations, a recurrent theme was how playing the Grateful Dead repertoire in this era feels different than just covering a famous band. I’ve felt this so strongly myself, with my own project Dead to the Core. It’s like you’re tapping into something bigger, more elemental, more communal, that’s not ultimately about the performer at all. You’re in a musical world in which the Dead itself is present, of course, but so are all the musicians whose voices they carried—Reverend Gary Davis, Hank Williams, Merle Haggard, Elizabeth Cotten, Obray Ramsay, Joseph Spence, Elmore James, Jesse Fuller, Chuck Berry, Cannon’s Jug Stompers, and so many more from the expanse of American roots music.

ADVERTISEMENT

Grateful Dead music, as Sam Grisman puts it, is “becoming its own genre or musical universe. One of the strongest suits of American culture is our folk music, and the Grateful Dead have become a huge part of that by advocating for their favorite folk music. And then through this process of time marching slowly on and their music enduring, a lot of their songs are just becoming a part of that folk canon. It’s certainly an honor to participate in the communion that these songs make possible, and to be able to build a community of fans and friends and musicians who care so much about this music and want to see it grow and live and adapt.”

Grahame Lesh, too, notes how universal the Dead’s music has become. “Last weekend I was sitting in on ‘Cassidy,’ the Bobby song, with moe., and not that long ago, I was with the Infamous Stringdusters and playing a Dead song,” he says. “The music is everywhere, and in every style. All the musicians who are digging into this music, whether they’ve been doing it for a month or forever—they’re so good, and it’s so cool to hear so many different takes. Not a lot of music can withstand that many interpretations.

“To me, it’s just the most American music. I feel like in 300 years, so much of what is more popular and well known now will have fallen away, and some of these songs will still be there. It is Americana—if that word is to mean anything, it’s ‘Ripple.’”

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2024 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.