Exploring James Taylor’s Singular and Sophisticated Guitar Style

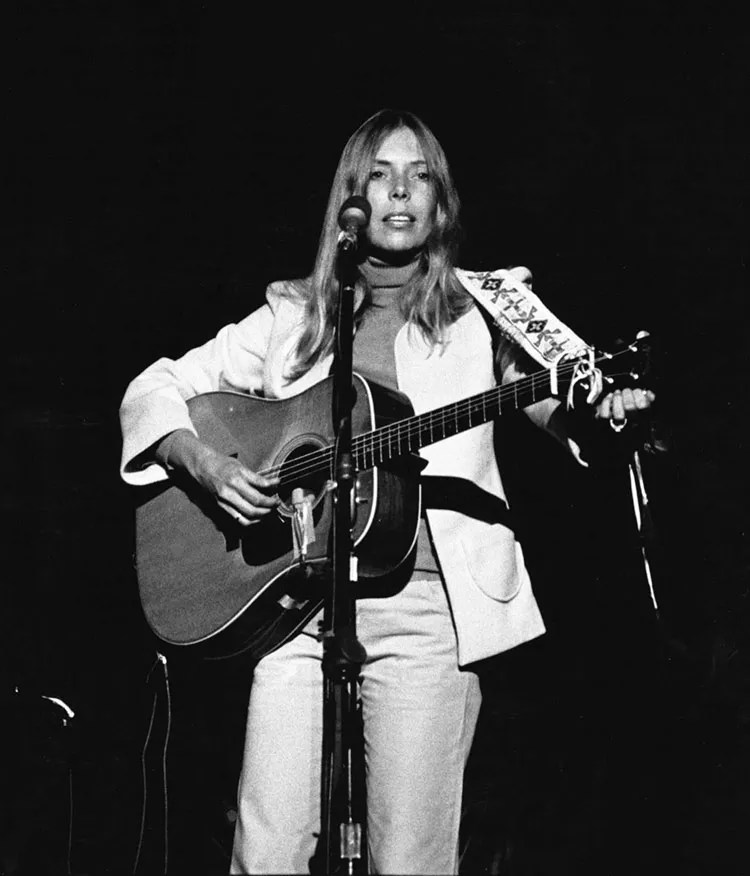

In 1968 James Taylor was 19 years old, a budding songwriter with ambition but no real plan, when he got what he has called “the mother of all big breaks”: a private audition for none other than Paul McCartney and George Harrison, arranged by Apple Records’ talent scout Peter Asher. Taylor, despite his jitters over meeting two of his musical heroes, brought out his Gibson J-50 and fingerpicked his song “Something in the Way She Moves.”

More than 30 years later, while inducting Taylor into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, McCartney recalled his first impression of Taylor as a “haunting guy who could really play the guitar and really sing beautifully.” McCartney and Harrison not only gave the young musician the thumbs-up, opening the door for Taylor to become the first non-Beatle signed to Apple, but Harrison later even paid the ultimate compliment by nicking Taylor’s title phrase to create a song of his own called “Something.”

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this story, though, is that Taylor himself, still a teenager, already had discovered so much of what would define his music across his career. The graceful melodies, the subtly unfolding harmony, the emotional intimacy in the words and in his smooth baritone, the guitar figures that became his trademark—the essentials of his style were fully present.

“I think that my musical style developed really in a vacuum,” Taylor told me in a 1992 interview for Acoustic Guitar (later published in the book Rock Troubadours). “It developed in North Carolina with a lot of time on my hands, empty, open time, and I think that’s true of a lot of musicians who develop their own thing. It takes a lot of time to practice, and it takes a certain amount of alienation to want to do that instead of wanting to do social things. It means that you in some way are cut off.”

While many artists take years of shows and albums to come into their own, and then continue to search and experiment in order to stay inspired, Taylor found the well of his music so early on—and it’s never dried up. Somehow, his music seems to exist outside of musical fashions and the times. In sound and spirit, the songs on Taylor’s 2015 album, Before This World, are clearly tied to “Carolina in My Mind,” “Fire and Rain,” “Sweet Baby James,” and other classics from decades before.

In Taylor’s music, the guitar provides much more than accompaniment. His singular approach to the instrument—picking style, chord choices, bass lines, melodies, embellishments—creates a landscape that’s fundamental to the songs. Even after a 50-year reign as one of our defining singer-songwriters, the source of standard repertoire played by countless acoustic guitarists, Taylor still stands out as a highly unusual player—with idiosyncratic technique and a sense of harmony far apart from the standards of folk or rock guitar.

In this lesson we’ll explore what makes Taylor’s guitar work so distinctive, and play examples inspired by his ageless songs.

The Way He Moves

The first stop on this tour of Taylor’s guitar style is, naturally, “Something in the Way She Moves,” first released on his self-titled Apple debut in 1968—and rerecorded a few years later in a more relaxed take for his blockbuster Greatest Hits.

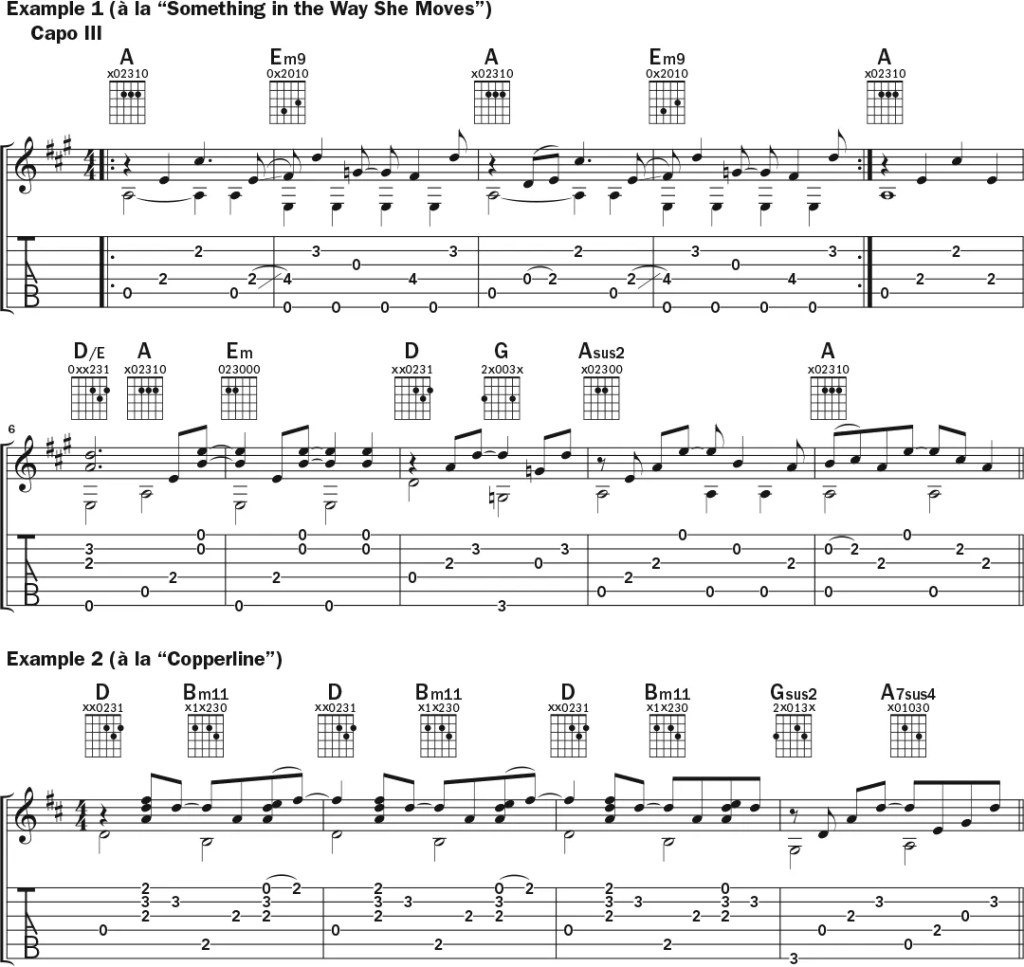

Put away the flatpick, grab a capo, and try Example 1, based on the intro and opening of the verse. As with everything in this lesson, pick the down-stemmed notes with your thumb and the up-stemmed notes with your fingers.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many of the core elements of Taylor’s style are in evidence here. He tends to play in A, D, and E, capoing up as needed for his voice, rarely higher than the third or fourth fret. In this example, capo at the third fret and play A shapes, which sound in the key of C. Change chords frequently, picking a prominent bass line. And in the last measure, tag the phrase with an A-chord hammer-on that is a JT signature.

Also notable is what is not here: a steady alternating or monotonic bass, or any kind of set picking pattern. In bars 1 and 3, pick the bass notes on beats 1 and 4; in bars 2 and 4, on every beat; and in bar 5, only on the downbeat. Taylor’s style is based far less on repeating patterns or arpeggios than conventional folk/country fingerpicking. It’s more akin to keyboard playing, with the two hands working independently. The thumb leads with the bass line, and the fingers fill in around it with partial chords, single notes, and melodic figures.

JT-Style Fingerings

One major quirk of Taylor’s technique is his use of what he calls “backwards” fingerings for D and A, with the index finger on top, as shown in this lesson’s chord diagrams. Check out Taylor’s YouTube guitar lessons for a close-up look at these fingerings, which he credits for helping him develop his signature hammer-ons and pull-offs (on the first string on the D, and on the second string on the A). For me personally, Taylor’s fingerings for D and A are just plain awkward. Most of the time it’s possible to work around them, as I did in the lesson videos. See how they feel to you.

There are JT guitar moves that just work better with his fingerings, however, such as the main rhythm pattern in his great ’90s song “Copperline,” shown in Example 2. If you fret the first string on the D with the index finger (as he does), your index can easily shift over to the fifth string to fret the Bm11 bass note, then return to the first string for the hammer-on going back to D. Taylor’s fingering is a likely reason he found this riff in the first place.

Rural Routes

Taylor’s Apple debut—recorded in the same studio around the Beatles’ White Album sessions—introduced such enduring songs as “Something in the Way She Moves” and “Carolina in My Mind,” and also showcased his feel for R&B in songs like “Knockin’ Around the Zoo.” But the album never quite broke through commercially—not helped by the fact that Taylor was out of commission for a while after its release, kicking a heroin addiction that dogged him for years.

The second time was the charm, though: Taylor’s 1970 follow-up album, Sweet Baby James, struck a deep chord, bringing him to the forefront of the emerging singer-songwriter movement. With the title track as well as “Fire and Rain” (transcribed in the January/February 2020 issue) and “Country Road,” Sweet Baby James may as well be a greatest hits collection.

While Taylor mostly sticks with standard tuning, he does sometimes use dropped D—notably on “Country Road.” Example 3 is based on the “Country Road” intro. After an opening bass run, play the D chord pull-off/hammer-on riff that he uses, with many variations, throughout his repertoire. He applies the same basic pattern to the A chord. Except for the quick bass runs at the ends of measures 2 and 4, play the low D as a pedal tone throughout, as the chord above it changes from D to C to G. The resulting C/D and G/D are two examples of pianistic slash chords, as used elsewhere in this lesson.

For clarity, pick the chord tones simultaneously with your fingers rather than strumming across them. As Taylor continues in “Country Road” and in other songs, though, he freely mixes fingerpicking with strums on the high strings—flicking up and down with one or two fingers. He keeps longer nails on his right-hand thumb and fingers, and in fact he has a YouTube tutorial on reinforcing his nails with layers of fiberglass tape, which keeps them intact and helps him achieve a bright tone without fingerpicks.

Turning the Wheel

Right from his earliest albums, Taylor has used a wider harmonic vocabulary than the simple, repetitive chord progressions of folk, country, and rock. One pivotal influence was church music. In his audio memoir, Break Shot, he said that hymns such as “Once to Every Man and Nation,” “Jerusalem,” and “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel,” which he first heard while attending boarding school in Massachusetts, were “bedrock stuff.” He added, “Those hymns were a musical education to me. I learned them on the guitar, and they taught me all I know.”

The hymn connection makes sense especially as an inspiration for the constant chord movement in Taylor songs, which recalls the way an organist reharmonizes a hymn differently with each pass. Even in a folky song like “Sweet Baby James,” Taylor changes chords almost every measure, cycling around D, Bm, G, A, F#m, and E in an unpredictable way.

Rather than laying out in, say, repeating four-measure blocks, Taylor’s chord progressions keep changing. He uses the apt metaphor of a wheel. As he put it in my AG interview, “I just basically get a wheel rolling and then hop on the thing and try to ride it.”

A Touch of Jazz

Another key influence on Taylor’s harmonic sense came from the standards and show tunes he heard in the family record collection and on periodic visits to Broadway. An early sign of that can be heard in Taylor’s take on Stephen Foster’s “Oh, Susannah,” recorded on Sweet Baby James. Rather than accompanying the song with the usual I, IV, and V chords, Taylor overlays a lightly jazzy progression.

In Example 4, capo at the third fret to play again in A (sounding as C), using all seventh chords. In measures 4 and 7, hold the Bm7 shape and just switch to a bass note to the open sixth string for the D/E. Taylor frequently uses voicings like this, with the bass note of the chord raised a step (as in C/D, A/B, etc.). Play freely, in sync with the vocals, and mix chords and arpeggios as you like.

“My music doesn’t sound like jazz to me,” he said when I asked about the extended chords he uses. “There are some simple jazz chords—some 13ths and augmented fifths, I play a lot of major sevenths and plus twos—but really a limited jazz vocabulary, for sure, and also very low on the neck, and usually keeping to the root of the chord in the bass.”

Another early song that showcases Taylor’s elegant use of extended chords is “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight,” released in 1972 on One Man Dog. Example 5, based on the first part of the verse, opens with an Em9 that is a common Taylor shape. Don’t bother fretting the fifth string, since you’re not playing it. Keep your fretting fingers in place on the top two strings, and move the bass note to the open fifth string, for the A13sus4. Then a lovely Dmaj9 to F#dim7 change brings you back around to the Em9 and the next turn of the wheel.

ADVERTISEMENT

In measures 7 and 8, notice also the classic Taylor change from Bm7 to E9/B and back to the Em9. The sound is more akin to a jazz/pop piano ballad than a typical guitar tune.

All About the Bass

While Taylor’s songs are often packed with chord changes, they don’t feel dense or busy, especially because he plays chords so sparingly. Bass lines really drive the progressions. Taylor’s first instrument was cello, which may well be one reason he brought that orientation to guitar. In many Taylor songs, you could play the bass line by itself behind the singing and get the gist.

That’s the case with “The Frozen Man,” from 1991’s New Moon Shine. The song was sparked by a National Geographic story about a 19th-century polar explorer whose corpse was preserved in the ice for 100 years—though Taylor has commented that the true topic is his father, who actually spent two years in Antarctica as a medical officer.

In Example 6, based on the opening of the verse, play chords in the key of D, using the inversions D/F# and D/A to hold off the resolution (to the D root) until the end of the phrase. Play sparsely while singing, and add short bass runs and riffs, like those in measures 4 and 7, during pauses in the vocals.

Fingerstyle Melodies

In a number of songs, Taylor picks a guitar melody—distinct from the vocal melody—to create an instrumental intro or interlude. One nice example is “Mexico,” from 1975’s Gorilla, which opens with a little fingerstyle instrumental before kicking into the song’s main Latin-style groove.

In Example 7, capo at the second fret and use open chord shapes in the key of E (sounding in the key of F). Focus on the bass and the melody, using few other chord tones. As in much of Taylor’s music, both the melody and the chord changes are highly syncopated, anticipating the downbeats throughout. Note also the measures of 2/4 that break up the 4/4 meter. For another example of this kind of fingerstyle piece, check out “Enough to Be on Your Way” (transcribed way back in the July 1998 issue), which opens with an instrumental that sounds like a traditional Celtic tune.

Brazilian Spice

Starting in the ’60s, Taylor tuned into Brazil’s bossa nova scene, and he cites composer/instrumentalist Antônio Carlos Jobim as having a big impact on his music. You can hear the Brazilian influence in a Taylor song like “Secret o’ Life,” from JT (1977), with its gently swaying rhythm and jazzy changes. In 1985, he celebrated his experiences performing in Brazil and soaking up its vibrant music culture in the song “Only a Dream in Rio.”

Taylor’s song “On the 4th of July,” a standout from his 2000 release, October Road, is another that clearly taps into bossa nova. Example 8 shows a pattern similar to the first part of the verse. Play bass notes on beats 1 and 3, each followed by a chord on an offbeat. The one-finger A/B is a JT chord used in many other songs. He also often plays F#m7 with a one-finger barre—not fretting or picking the fifth string.

Later in “On the 4th of July,” Taylor sings a series of phrases on a single melody note while the harmony changes underneath—an effect famously used in Jobim’s “One Note Samba.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Back to the Well

On Taylor’s most recent album, 2020’s American Standard, he returned to the show tunes and standards that were such a formative influence—from “My Blue Heaven” to “God Bless the Child” to “The Surrey with the Fringe on Top.” What’s satisfying about the project is that he did not, say, sing standards with a pianist, jazz combo, or orchestra; instead, he played them as guitar-driven James Taylor songs, with some guitar support from John Pizzarelli. When Taylor kicks off “Moon River,” the intro is straight out of “Something in the Way She Moves.”

The last example in this lesson is based on his version of “Teach Me Tonight,” written in the ’50s by Gene de Paul and Sammy Cahn. Taylor’s recording on American Standard has two guitar parts, one supplying soft bossa-style chords and the other playing more ringing arpeggios. Example 9 is based on the latter part, with a sweet-sounding set of chords that—unlike with typical jazz guitar—mostly use open shapes. In measure 5, hold a Bm7 and move the bass note over to the sixth string for the E7sus4—a characteristic JT move. The open Amaj9 voicing in measure 7 is another chord that instantly marks this as a Taylor arrangement.

Guitar Lessons from JT

Taylor’s guitar style is so distinctive and dialed in that it’s deceptively hard to reproduce. But for any guitar-playing singer-songwriter—or any guitarist creating accompaniment parts—there are some key takeaways.

- Think bass. A clear, purposeful bass line can have so much more power than a series of block chords.

- Use inversions and slash chords. Try voicings with notes other than the root on the bottom to add richness to a progression. Slash chords can also help you develop smooth bass lines that move in half and whole steps rather than jumping around. See the examples of slash chords throughout this lesson, including D/A, D/E, D/F#, G/D, C/D, A/B, and E9/B.

- Extend the chords. Notes beyond the basic triad can add so much color to the harmony, as you can hear in the sus4, seventh, ninth, 13th chords and more in these examples. As Taylor’s songs prove, these types of chords do not necessarily entail pretzel fingerings. Many are available with easy open chord shapes.

- Look for connecting notes. One key to the flowing sound of JT’s guitar parts is that he often uses one or more common tones when changing chords; basically one finger (or more) stays put from one chord to the next, or the same open string rings through.

- Syncopate. Try changing chords or playing a guitar melody note on an offbeat. These examples are chock full of chord changes and melodies that hit before the downbeat, creating a lot of momentum.

- Spotlight the vocal. Embellishments and riffs are great, but save them for breaks in the vocal. Across Taylor’s repertoire, his guitar provides unobtrusive support to the singing, then in effect steps up to the mic between vocal lines to add accents, like mini instrumental breaks.

Guitar is surely not the only or even the main reason why people have so deeply connected with Taylor’s songs for so long. His melodies, words of empathy, and soothing voice are at the center. Yet it’s remarkable that his fingerprint as an artist can be heard in every detail of his guitar work, even in the chord vocabulary.

Taylor’s songs were among the first I ever played, and revisiting them for this lesson felt like a homecoming—to a place that’s both familiar and new again.

In Tune with JT

One intriguing detail of Taylor’s guitars is the way he tunes them. As he’s demonstrated on YouTube, he uses a tuner that shows cents in order to tune all the strings slightly flat, from three cents below standard pitch on the first string to 12 cents flat on the sixth. This is to compensate, he says, for the way bass strings tend to ring sharp and a capo tends to pull everything slightly sharp.

ADVERTISEMENT

With fixed frets and the compromise system of equal temperament, a guitar is never perfectly in tune in all keys, so Taylor’s tuning system just makes it right for his ear. “The tolerance for tempered tuning is different for different people,” said the late luthier Rick Turner. “Some are painfully aware of the ‘out of tuneness’ of certain intervals; most are not.”

What He Plays

Taylor got started on a plywood nylon-string that his brother Alex eventually painted blue and used for slide. By the time of James’ fateful audition with the Beatles, he was playing a Gibson J-50 that was his main guitar for around a decade. Other guitars in his collection include Takamine and Yamaha models he’s used onstage, and custom instruments by Mark Whitebook and Kenji Okumura.

For over 30 years, his steadfast companions have been guitars made by Minnesota luthier James Olson. Taylor has Olsons in a variety of sizes and styles, but his main guitars, as celebrated years ago in a JT signature limited edition, are Olson SJs with cedar tops and rosewood backs and sides.

Many of the teachers who contribute lessons to Acoustic Guitar also offer private or group instruction, in-person or virtually. Check out our Acoustic Guitar Teacher Directory to learn more!

I love JT’s fingerpicking and just discovered your article about it. It is terrific. Can you tell me where I can find the partial TABs you used? I would like to purchase complete ones for his music. Thanks! Dana