Guitar Lesson: 10 Seminal Moments in Fingerstyle Guitar History

The legendary classical guitar virtuoso Andrés Segovia famously described the guitar as a small orchestra, and generations of steel-string guitarists, armed with six strings and ten fingers, have pursued and expanded that potential. A range of fingerstyle techniques has allowed these musicians to function like a complete band, creating independent melodies, bass lines, harmony, and even percussion on a single guitar.

In this lesson, we’ll explore ten key recordings and artists who have significantly shaped the landscape of modern fingerstyle guitar, with examples that have helped expand the genre beyond the fundamental alternating bass or Travis picking approach. We’ll learn from pioneers who merged folk music and blues with early Renaissance music, those who created unique textures through the use of alternate tunings, and adventurous guitarists who blazed fresh ground with entirely new techniques, laying the groundwork for all of us to find new creative possibilities on the instrument.

1. Davey Graham

“Anji”

The English music scene in the 1960s usually evokes memories of the British Invasion—bands like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Kinks, and the Yardbirds. But there was also a thriving folk scene that included guitarists like Davey Graham, John Renbourn, Bert Jansch, and more, and their music is well worth studying.

In addition to being credited as the inventor of DADGAD tuning, Graham wrote and recorded the instrumental solo fingerstyle piece “Anji,” which is considered one of the quintessential pieces of standard fingerstyle repertoire to this day. “Anji,” released in 1962 on a three-song EP, 3/4 A.D., that Graham recorded with British blues legend Alexis Korner, was a huge influence on a generation of upcoming fingerstyle players, including Jansch and Renbourn.

Jansch recorded his version of “Anji” on his debut album, which achieved more commercial success than Graham’s original. Paul Simon offered a version on Simon and Garfunkel’s Sounds of Silence album, introducing it to a global audience. Nancy Wilson of the rock band Heart learned to play the composition as a teenager, and later used it as inspiration for her acoustic introduction to Heart’s hit “Crazy on You.”

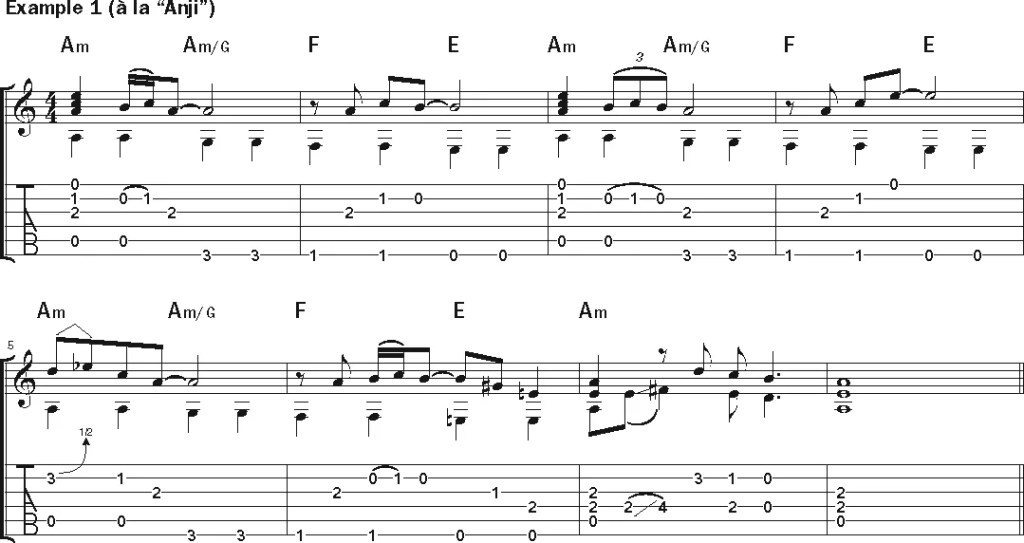

A distinctive element of “Anji,” as illustrated in Example 1, is its descending bass line (A–G–F–E) paired with a syncopated melody. The primary challenge of playing the tune lies in maintaining the steady quarter-note bass line along with the intricate melody parts, including hammer-ons, pull-offs, sixth intervals, and bluesy string bends. The song lends itself to variations, expansion, and improvisation, as you can hear by comparing Graham’s original with versions by Renbourn, Jansch, and Simon, as well as Wilson’s derivation. Once the bass line becomes second nature, try creating your own melodies and improvisations. (For a deeper dive into Davey Graham’s life and music, as well as a note-for-note transcription of “Anji,” see the April 2016 issue.)

2. John Renbourn

“The Earle of Salisbury”

John Renbourn had a strong interest in medieval English music and merged lute music, English traditional folk, and Irish and other Celtic influences, along with jazz and blues, into a style that became known as baroque folk. Renbourn’s 1968 album, with the lengthy title of Sir John Alot of Merrie Englandes Musyk Thyng & Ye Grene Knyghte, captures the range of his early style, from an interpretation of “The Earle of Salisbury,” a pavane written in 1612 by William Byrd, to a solo fingerstyle arrangement of “My Sweet Potato” by Booker T. and the MG’s, along with some original compositions.

Originally composed for keyboard, “The Earle of Salisbury” (see complete transcription in the January/February 2020 issue) was popularized as a guitar piece through Renbourn’s solo arrangement. Example 2 mimics the feel and key features of the tune, intertwining a simple melody, bass line, and moving inner voices or countermelodies. You could easily imagine this example being played by multiple instruments in a small ensemble, each with its own lines.

ADVERTISEMENT

3. Leo Kottke

“The Driving of the Year Nail”

Graham, Renbourn, and other British fingerpickers also drew inspiration from the music being created by a thriving fingerstyle community in the United States. Early blues and ragtime players, including Blind Blake, Robert Johnson, and Reverend Gary Davis, set a high bar for instrumental technique. Chet Atkins, Merle Travis, and others defined the foundational alternating bass style that became known as Travis picking.

Another group of musicians pioneered a style known as American Primitive guitar, a fingerstyle approach that blended minimalism with traditional folk and blues fingerpicking. A central figure of the movement, John Fahey, founded Takoma Records in 1959. The label released recordings by a range of artists, including Fahey himself, but it was the 1969 release of 6- and 12-String Guitar by Leo Kottke that became Takoma’s biggest seller.

Kottke’s powerful and distinctive approach continues to be a major influence on fingerstyle players today. His style creates a wall of sound, and his music tends to have a unique angular feel. While many of his compositions rely on conventional alternating bass patterns, Kottke artfully combines syncopated accents with a high-speed, driving attack that tends to disguise the underlying alternating bass pattern, ultimately sounding quite different from standard Travis picking. And though he often uses open tunings like D, G, or C, he is known to play in standard as well.

Example 3 is inspired by “The Driving of the Year Nail,” the opening track of 6- and 12-String Guitar. To emulate Kottke’s signature sound, try playing the example on a 12-string guitar in standard tuning, but with all strings lowered by three half steps. Played in the key of G, the example uses primarily open G and C chord shapes.

4. Alex de Grassi

“Turning”

Another U.S.-based genre of fingerstyle guitar, a style that came to be known as new age, formed around the Windham Hill record label. Guitarist-composer Will Ackerman founded the label after recording his 1976 debut album, In Search of the Turtle’s Navel, and soon added other musicians to the roster, including Michael Hedges and Ackerman’s cousin Alex de Grassi. In his 1978 release, Turning: Turning Back, de Grassi leveraged sophisticated technique, advanced compositional skills, and a diverse set of alternate tunings to create an impressionistic blend of his diverse influences.

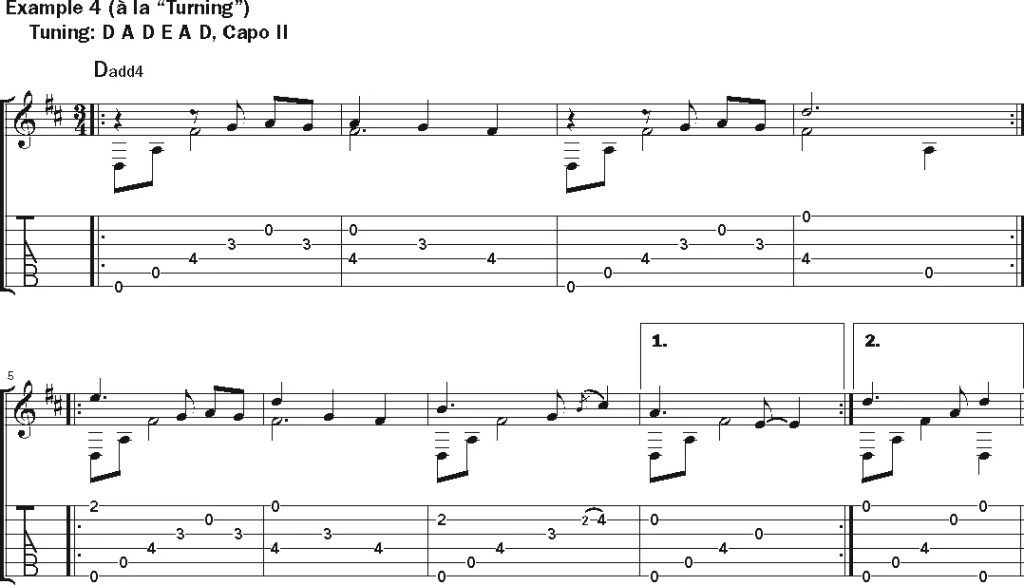

Example 4 is inspired by the first track on Turning: Turning Back, based on a tuning de Grassi has frequently favored: lowest string to highest, E B E F# B E. This requires that strings 4 and 5 be tuned up a whole step; as a workaround, you can tune to D A D E A D (like DADGAD, but with string 3 lowered to E) and place a capo at the second fret. Play this figure delicately, letting all the strings ring and sustain as much as possible. Starting in the fifth measure, the notes on strings 1 and 2 form the melody, so focus on making these stand out while sustaining both the melody and the arpeggiated accompaniment.

5. James Taylor

“Fire and Rain”

Perhaps more people have been introduced to the sounds and possibilities of fingerstyle guitar through popular music, folk, and rock than by purely instrumental performers. For example, English folksinger Donovan taught Paul McCartney and John Lennon the art of fingerpicking, leading to iconic tunes like “Blackbird” and “Julia.” Fingerstyle guitar plays a role in classics like Kansas’ “Dust in the Wind,” Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide,” and many more.

James Taylor stands out as one of the artists to have Top 40 hits while also having a major impact on fingerstyle guitar. Taylor’s album Sweet Baby James, from 1970, not only catapulted him to fame but helped popularize the singer-songwriter movement that continues to this day. While most of Taylor’s tunes are fully produced with a backing band, his gentle solo fingerstyle guitar is a critical component, and his unique phrasing and distinctive style have influenced even solo instrumental fingerstyle players.

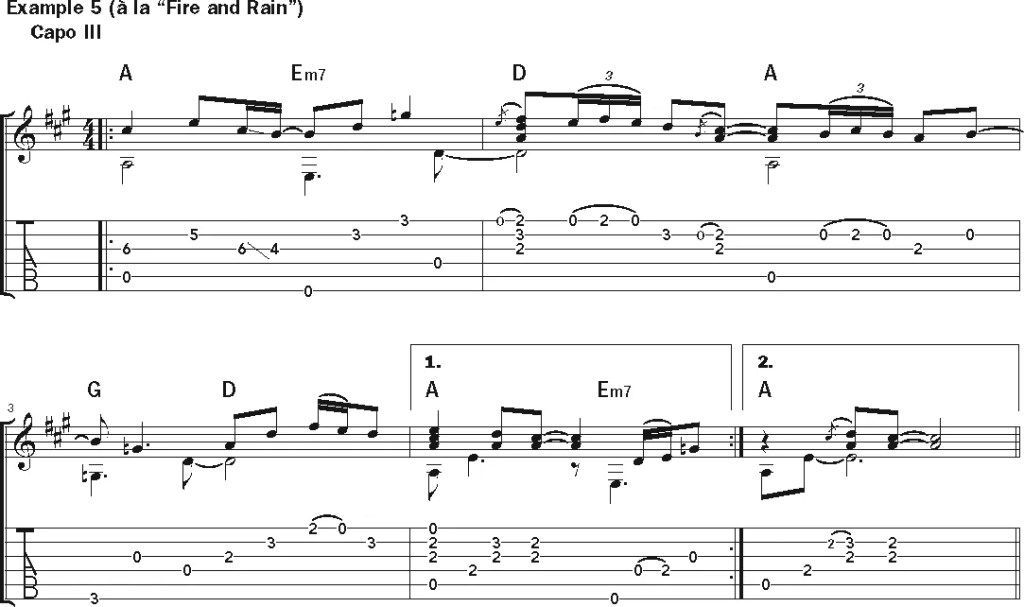

Taylor typically plays in standard tuning or dropped D, often using a capo at the second or third fret. This not only changes the key but the tonality of the guitar, giving it a sweeter, more delicate sound. Taylor’s signature style includes the frequent use of hammer-ons, pull-offs, and slides, especially on open D and A chords. Although his chord choices are usually straightforward, he often anticipates notes, especially in the bass register, creating suspensions and the impression of more complex harmony.

Example 5 is loosely based on the introduction to Taylor’s classic “Fire and Rain.” (Find a complete transcription of the song in the January/February 2020 issue, plus a feature on his guitar style in July/August 2022.) Capo at the third fret, and pay special attention to all the hammer-ons, pull-offs, and syncopated timing.

ADVERTISEMENT

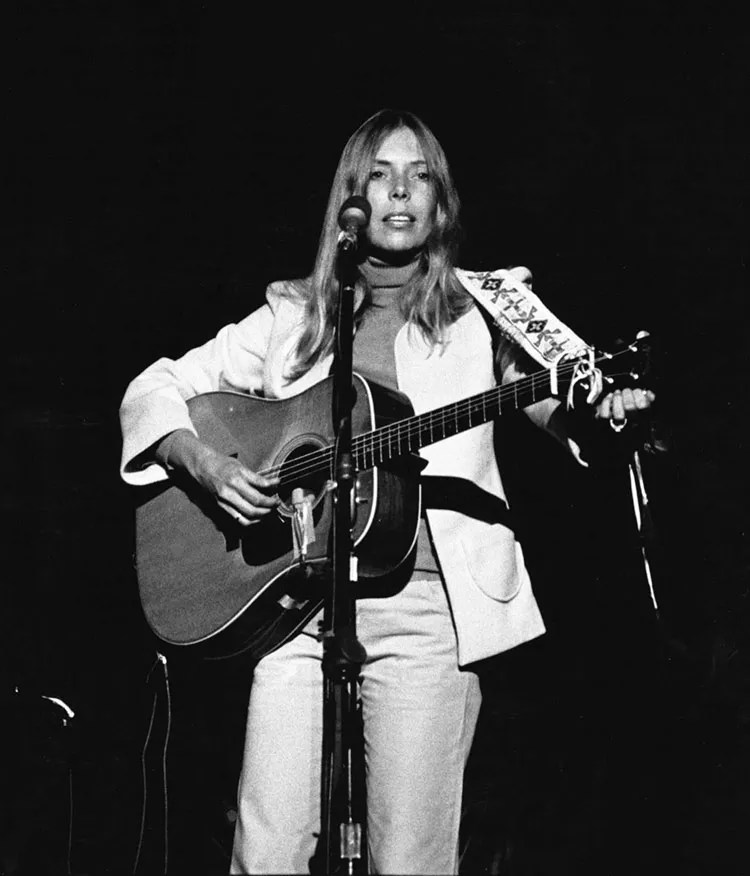

6. Joni Mitchell

“I Had a King”

Joni Mitchell is another popular singer-songwriter who has had a significant impact on fingerstyle guitarists, primarily due to her extensive use of alternate tunings and distinctive picking patterns. Mitchell’s playing generally involves simple chord shapes, but by changing tunings—she has used more than 50—she is able to create distinctive soundscapes. As a painter, Mitchell tended to think of sounds in terms of colors and texture, using alternate tunings to create complex sounds with dissonances and chords that are difficult to give traditional names. Her influence can be felt in some of the music of Windham Hill artists like Will Ackerman and Alex de Grassi.

Example 6 is inspired by Mitchell’s “I Had a King,” from her early album Song to a Seagull (1968). According to the Joni Mitchell Complete So Far… songbook, the original track uses the tuning E B E E B E with a capo at the fifth fret; in this example, you get the same open string pitches by tuning to D A D D A D (like DADGAD, but with string 3 tuned down to unison with string 4) with a capo at the seventh fret. The example consists of steady 16th notes, arranged in a series of arpeggios that create a syncopated pattern. Note how simple chord formations here produce colorful harmonies through shifting relationships between fretted notes and open strings. For instance, in the first bar, what would be an open-E shape in standard tuning produces a Dadd4 chord (sounding as Aadd4 due to the capo), and when the shape is moved down two frets it creates a jazzy, close-voiced Dm9 (Am9). Let the notes of each chord ring as long as possible to create a wash of color.

7. Pierre Bensusan

“Le Voyage pour L’Irlande”

Each generation of fingerstyle players builds on those that came before, mastering the earlier styles before breaking new ground, either in style, compositional approaches, the development of new techniques—or all three. The last four artists in this tour of modern fingerstyle—Pierre Bensusan, Michael Hedges, Tommy Emmanuel, and Andy McKee—have all made their mark in this way.

Près de Paris, the 1975 debut by French-Algerian guitarist Pierre Bensusan, revealed a wide range of influences, from traditional folk and Celtic music to baroque folk à la John Renbourn and even bluegrass. The album also showcased Bensusan’s adept use of a variety of alternate tunings. It was with his third release, Musiques (1993), that Bensusan exclusively embraced DADGAD tuning, for which he has become known. One of Bensusan’s contributions has been to demonstrate the musical depth that can be achieved with a dedicated focus on—and a full understanding of—an alternate tuning.

Bensusan has a unique touch and style that is challenging to emulate. He often displaces bass notes before or after where you’d expect them to fall, while creating intricate middle voices under a heavily ornamented melody. In spite of the intricacies, most of Bensusan’s tunes have a fairly straightforward and singable melody, which he embellishes and explores much like a jazz musician.

Example 7 is inspired by Bensusan’s composition “Le Voyage pour L’Irlande” (“Voyage for Ireland”), from Musiques. The figure demonstrates key aspects of Bensusan’s style, including hammer-ons, pull-offs, and displaced bass notes, along with the resonance of DADGAD tuning. It’s instructive to compare the original version on Musiques to more recent live performances or videos on YouTube, or “Return to Ireland” on his 2020 release, Aswan, to see how far Bensusan can stretch and expand on the original theme while still retaining its essential character.

8. Michael Hedges

“Bensusan”

Michael Hedges revolutionized fingerstyle guitar with the release of the Windham Hill albums Breakfast in the Field (1981) and especially Aerial Boundaries (1984). Both albums are essential listening for fingerstyle guitarists. Hedges, a trained musician who studied classical guitar and composition at the Peabody Conservatory, brought forth an array of groundbreaking techniques, establishing a new vocabulary for guitarists. His innovations included slap harmonics, right-hand tapped notes, explosive pull-offs, percussive effects, and more. Crucially, these techniques were not mere gimmicks; grounded in his background and training in 20th-century music composition, Hedges utilized these techniques to fulfill his musically sophisticated vision.

Example 8 is inspired by Hedges’ composition “Bensusan” (dedicated to Pierre Bensusan), the second track on Aerial Boundaries. The tuning, C G D G A C, is unconventional; Hedges uses a capo at the third fret, placing the tune in the key of Eb major. While the figure starts off in a fairly straightforward manner, measure 2 introduces several less-conventional techniques. Left-hand-tapped bass notes (a technique known as hammering-on from nowhere) create a percussive effect. Beat 4 features a slap harmonic achieved by striking the strings sharply at the 12th fret (relative to the capo) with the right hand. The bass note on the fifth string is then pulled off forcefully, sounding both the fourth and fifth strings—an explosive pull-off. (For a complete transcription of “Bensusan,” see the July 2005 issue.)

ADVERTISEMENT

9. Tommy Emmanuel

“Somewhere Over the Rainbow”

Tommy Emmanuel has long been a household name in his native Australia, where he grew up performing in a family band along with his brother Phil. Emmanuel’s solo style is characterized by catchy melodies, infectious grooves, and seemingly unlimited technical chops. Emmanuel was strongly influenced by Chet Atkins, and many of his signature tunes are firmly rooted in the Travis picking and Atkins alternating bass style, but he also ventures into new territory.

One of Emmanuel’s most impressive techniques is based on harmonics, leveraging an approach pioneered by the late jazz guitarist Lenny Breau, who passed it on to Chet Atkins. Example 9 is inspired by Emmanuel’s arrangement of the classic song “Over the Rainbow,” which starts with a tour-de-force based on this technique. The fundamental idea involves alternating between artificial harmonics and conventionally fretted notes. When done smoothly and up to speed, the technique produces a dramatic harp-like effect.

For the first chord in our simplified example, barre at the ninth fret with your fretting hand’s first finger. Keeping that finger held down, produce the artificial harmonics by lightly touching each string with your index finger at the 21st fret (which may be beyond the end of your fretboard) while plucking it with your thumb. Meanwhile, sound the regular ninth-fret notes with your picking hand’s ring finger. In measures 3 and 4, you’ll need to fret the B7 and E9 chords in the usual way and adjust the location of the harmonics—always 12 frets above the fretted note, tracing the shape of the chord with your picking hand as you play the harmonics.

10. Andy McKee

“Drifting”

Younger generations of fingerstyle players like Mike Dawes, Jon Gomm, Kaki King, Antoine Dufour, Christie Lenée, Alexandr Misko, and many others continue to expand on technical innovations of pioneers like Michael Hedges, while also in many cases being influenced by newer styles of popular music, including rock, metal, and hip-hop. One common characteristic of contemporary fingerstyle, percussive techniques combined with two-handed tapping, owes much of its popularity to Andy McKee.

Andy McKee’s “Drifting” marked a sea change in the fingerstyle guitar world in several ways, not only through the tune itself but in the way it came to the public’s attention. McKee originally released the tune on Nocturne (2001), a self-released album he sold at coffeehouse gigs. But in 2005, McKee signed with a new fledgling label, Candyrat Records, which encouraged him to shoot videos of his tunes and upload them to a then-new website called YouTube. When YouTube featured the video showcasing McKee’s percussive two-handed tapping techniques on its home page, the video quickly garnered over a million views, helping to launch McKee as an international touring and recording artist. The video now boasts over 60 million views.

ADVERTISEMENT

McKee was not the first to use the techniques displayed on “Drifting”—many were pioneered by Michael Hedges, and extensively explored by Preston Reed, whom McKee credits as the inspiration for the tune. But it was McKee’s video performance that brought these techniques, now considered essential aspects of modern fingerstyle guitar, to a wider audience.

Example 10 demonstrates the key elements of McKee’s approach. The fretting hand taps chords on the bottom three strings, reaching over the top of the neck, striking the strings with one or more fingers; you can use your first finger alone, but doubling with your second finger adds strength. In between, both hands hit various parts of the guitar, creating distinct percussive sounds: the top of the guitar at the lower bout for a kick drum sound; above the soundhole for a tom sound; and the side of the guitar near the neck for a snare sound.

Measure 2 ends with a slap harmonic, played by striking the top three strings at the 12th fret with the index finger of your picking hand. Starting in measure 3, the picking hand plays a melody by tapping on strings over the fretboard—hammering on, pulling off, and sliding with the picking-hand index finger while the fretting hand maintains the bass pattern. Mastering this example requires a choreographed movement that will take a bit of practice if you have only used traditional guitar picking techniques.

A Constantly Evolving Landscape

There is much to learn from these artists’ innovations: groundbreaking techniques, different tunings, harmonies, approaches to composition and style—all in the pursuit of a more complete, orchestral sound from the guitar. Their music continues to provide inspiration to new players and professionals alike.

Of course, for each of the artists mentioned here, there are not only more songs to listen to and learn from, but also many related guitarists to be discovered. The landscape of fingerstyle guitar is constantly evolving, and each generation of guitarists develops unique styles and invents new techniques, providing even more sources of inspiration for us all.

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2024 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.

Many of the teachers who contribute lessons to Acoustic Guitar also offer private or group instruction, in-person or virtually. Check out our Acoustic Guitar Teacher Directory to learn more!

What? No mention of Jorma Kaukonen?

Amazing list! I’ve been a long-time fan of Andy McKee and Tommy Emmanuel, but your post turned me on to some other incredible fingerstyle players I wasn’t familiar with before.

What do you think of the South Korean guitarist Sungha Jung? Though maybe not as groundbreaking as others on this list, I would argue he has definitely carried the torch and introduced fingerstyle guitar music to whole new generation of players.

Anyway, awesome post and thanks for the tabs/transcriptions!