An Exploration of Doc Watson’s Innovative and Joyful Guitar Stylings

Flatpicking pioneer Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson was born in 1923, but it wasn’t until nearly 40 years later that his musical career began in earnest. In the early 1960s, traveling folklorist Ralph Rinzler came across Watson while recording other area musicians and, amazed by his talent, encouraged him to join the burgeoning folk revival scene.

Within a few short years this blind guitarist from the mountains of North Carolina rose to prominence and for the next five decades charmed audiences with his easygoing, joyous, and captivating picking, singing, and storytelling. Watson passed away in 2012, at the age of 89, but his legacy lives on through the guitar stylings he created, his many recordings, the annual MerleFest music festival he founded in his son’s memory, and the countless lives he has touched through his music, humor, and positivity.

Watson was an astonishing guitarist who practically invented bluegrass flatpicking and redefined the Travis-style approach to fingerpicking (see the transcription of “Doc’s Guitar” in the July-August 2023 issue), though he always humbly denied these facts. His lifelong musical accomplishments are innumerable, but what sets Watson apart from the multitude of acoustic guitar giants is the sincerity and joy in everything he did. Watch any live video footage of him performing and you will see that the person most enjoying the music is Watson himself—smiling, joking, encouraging his bandmates, telling stories, and fully engrossed.

The musical niche Watson created came from unifying the wide array of styles that he grew up listening to and playing. He is often considered a folk musician, but I believe he simply played the music he loved in the way that felt most natural to him. Watson recorded traditional mountain songs and fiddle tunes (like “Tom Dooley,” “Little Sadie,” and “Black Mountain Rag”), songs from the country artists of his childhood (by Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, the Delmore Brothers, et al.), jazz standards (“Summertime,” “Sweet Georgia Brown,” and “Bye Bye Blues”), and songs from blues legends (Mississippi John Hurt, for one). There are even pre-1960 recordings floating around of Watson playing “Stardust” and other jazz tunes on an electric guitar.

This lesson breaks down Watson’s acoustic flatpicking, beginning with rhythm and backup, transitioning to his lead playing, and ending with the combination of the two. For those interested in more background, a wonderful biography by Dan Miller is available for free, along with a multitude of other resources, at the Doc’s Guitar website (docsguitar.com). In the meantime, enjoy this deep dive into Watson’s picking style, and let it bring some joyfulness into your playing and into your life.

ADVERTISEMENT

Boom-Chuck Rhythms

Watson’s rhythm playing was largely influenced by the guitarists he grew up listening to. He adopted the scratch of Maybelle Carter, the bass runs of Riley Puckett, and the syncopations of Jimmie Rodgers to form a hard-driving momentum that fell right into the pocket of whatever situation he was playing in. The basis for the majority of Watson’s rhythm work is the ubiquitous boom-chuck, consisting of a bass note on the lower strings on beats 1 and 3 (the boom, often played in an alternating pattern) and a downward strum on the upper strings on beats 2 and 4 (the chuck). Example 1a presents the standard boom-chuck pattern over a C chord using all downstrokes.

Watson used the standard boom-chuck often, but he also had variations to this pattern. Example 1b is another common strumming pattern of his, adding an upward strum on the “and” of beats 2 and of 4. With a chord tone picked using an upstroke between the boom and the chuck, Example 1c builds on the pattern in a different way. This approach appears often in Watson’s playing and is perhaps most obvious in his famous rendition of “Tennessee Stud”—more on that in a bit. Finally, Example 1d combines the previous examples into a full down-up pattern with a pick stroke on every eighth note.

Despite their basic appearance, these patterns are difficult to play convincingly. Take them slow, focus on correct pick direction, and ensure that the strums do not overpower the bass notes on beats 1 and 3. Watson would use many of these patterns within a given song, or even within a measure, often with the more basic versions (like 1a and b) while he was singing, and the busier versions (1c and d) as flourishes during vocal pauses. Careful listening to Doc’s playing on his more stripped-down recordings reveals how he did this; some of the best albums to track his rhythm stylings are Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson at Folk City (1963), Southbound (1966), Live Recordings 1963–1980: Off the Record Volume 2 (with Bill Monroe, 1993), and Doc & Dawg (with David Grisman, 1997).

Inspired by Watson’s backup while he sings the first verse of “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” on Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson, Example 2 is an excellent illustration of how he used the patterns shown above. Bars 1, 9, and 12–13 apply the Ex. 1a boom-chuck, while measures 3–5, 7, and 11 bring in the Ex. 1b rhythm. Note that Watson does not use a consistent alternating bass pattern but instead goes for walking bass movement, like the quick climb to D in bar 2 or the Riley Puckett–inspired bass line in bars 7–10. This example does not incorporate Exs. 1c or d, but you’ll see these put to use in later selections.

Extended Bass Lines

One of my favorite elements of Watson’s style is his use of extended bass runs while backing up other instrumentalists. A perfect display of this is during his duet with Bill Monroe on “Feast Here Tonight,” from Live Recordings 1963–1980. For Monroe’s mandolin intro, the first verse, and the first chorus, Watson primarily uses boom-chuck with a few short bass lines inserted throughout.

As Monroe kicks into his first solo, Watson switches to an extended bass line that adds momentum, interest, and a unique counterpoint to the mandolin, as shown in Example 3. Playing out of D, Watson runs up and down the strings, forming a walking bass line, and switches to boom-chuck only for a couple of brief sections. Every note is played with a downstroke, bringing drive and power to the line. Only in the penultimate measure does he break the quarter-note pattern, signaling the end of the solo before returning to boom-chuck for the verse.

Fiddle Tunes on Guitar

Watson amazed folk fans in the early 1960s by taking tunes typically reserved for the fiddle and reworking them for the acoustic with speed, clarity, and flash. He never claimed to be the first to play fiddle tunes on a guitar, but for the majority of listeners at the time it was an entirely novel and groundbreaking approach. Watson first began playing these tunes in the 1950s as an electric guitarist in a Western swing band. The group did not have a fiddler, and when audiences wanted a square dance set, Watson ran the melodies on his Gibson Les Paul. Later he transferred his fiddle-tune skills to the steel-string acoustic, giving way to what is now the well-established flatpicking style.

ADVERTISEMENT

“June Apple” is a jam favorite, and Watson’s rendition on Doc Watson in Nashville: Good Deal! (1968) is the standard approach for guitarists (Example 4). He kicks it off with “taters,” a two-bar shuffle that sets the tempo and tells the other musicians when to come in. The tune itself then starts with a pickup into bar 3 using a quick hammer-on. The key to playing this tune—or any fiddle tune in the style of Watson—is to maintain alternating picking, coordinating downstrokes to happen on the beats and upstrokes to happen on the ands. Watson adopted his style by mimicking fiddlers, and alternating picking helps maintain the rhythmic bounce of the fiddle by having the heavier downstrokes land in coordination with the beats.

Signature Licks

Some of the most recognizable features in Watson’s picking were the slick, bluesy licks that he employed in all kinds of situations: at the end of or within a solo, in between vocal pauses, or even as backup. Watson often played out of the C position with a capo, so the licks presented here are all in C. Example 5a is an abbreviated lick that he used all the time. It appears in his rendition of “Streamline Cannonball” on Good Deal! and throughout a multitude of his recordings and live performances. He would play it as is, alter it a little bit, like in Example 5b (from “Footprints in the Snow” on Treasures Untold), or a lot, as in Example 5c, which brings in triplets for the first half of the measure (from “Jimmy’s Texas Blues” on Doc Watson on Stage).

Another common lick of Watson’s is similar to the famous G-run but over the C chord—see Example 6a, patterned after “I’m Worried Now” on Portrait. As in the previous examples, Watson would alter it in a bunch of different ways, for instance, with the chromatic line shown in Example 6b. He also regularly used fast chromatic bass runs to fill in vocal pauses like in Example 7. Both Exs. 6b and 7can be heard several times on “Streamline Cannonball.”

Watson altered and combined these types of ideas to fit the context of the song. Example 8 comes to mind, a passage from his solo on “Ramshackle Shack” off Riding the Midnight Train. Notice that it doesn’t specifically use the licks shown previously, but it almost sounds as if it does. This is a special element of Watson’s style: He played naturally and intuitively and didn’t rely on exact licks but still retained his own familiar sound. [For more on how Watson weaved these types of lines into melody-based solos, check out “Footprints in the Snow” in the January/February 2022 issue and “Greenville Trestle High” in July/August 2022. –ed.]

Combined Rhythm and Lead

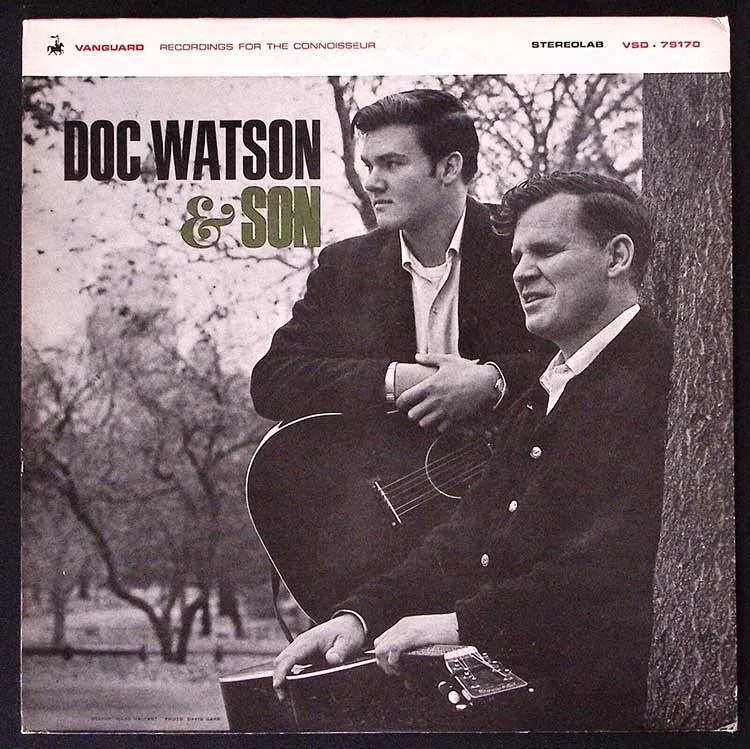

Watson’s most celebrated songs from early in his career are the ones in which he combined rhythm and lead together for an all-inclusive one-man show. He famously did this with Merle Travis–inspired fingerpicking on such songs as “Deep River Blues” and “Sitting on Top of the World,” but he did it with a flatpick, too. Two favorites in this style are “Tennessee Stud” from Southbound (1966) and “Little Sadie” from Doc Watson & Son (1965).

Watson played “Tennessee Stud” in open A position with a capo at the fifth fret, and began the tune with a flatpicked melody line in the lower register, similar to bars 1–3 of Example 9. He then transitioned to a rhythm-based pattern over the A and E minor chords that serve as a central hook in the song. Astute readers will notice it uses the same strumming shown above in Ex. 1c.

ADVERTISEMENT

Example 10 tips its hat to Watson’s intro and first verse for “Little Sadie.” He plays the flatpicked melody and the verse rhythm many times with some variations, and the first pass serves as a good model for what he does later in the song. Notice how throughout the melody passage Watson includes quick boom-chuck strums that give the listener context to the chords, like the partial D minor in the second half of bar 2, the partial C in the first half of bar 3, and the more obvious C in bar 5. This is the essence of Watson’s combined rhythm and lead approach, where he plays both melody lines and boom-chuck rhythm simultaneously.

Over the years flatpickers have built an entire musical style upon the groundwork that Doc Watson pioneered, as seen in this lesson’s cross section of his work. That said, the joy that Watson brought to the music seems to have taken a backseat compared to the flash and speed of modern bluegrass guitarists. Watson was indeed flashy and fast, but he was also really fun, and if there is anything you learn from his flatpicking style, I hope it is about harnessing and sharing the joy that playing music can bring.

ADVERTISEMENT

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2023 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.