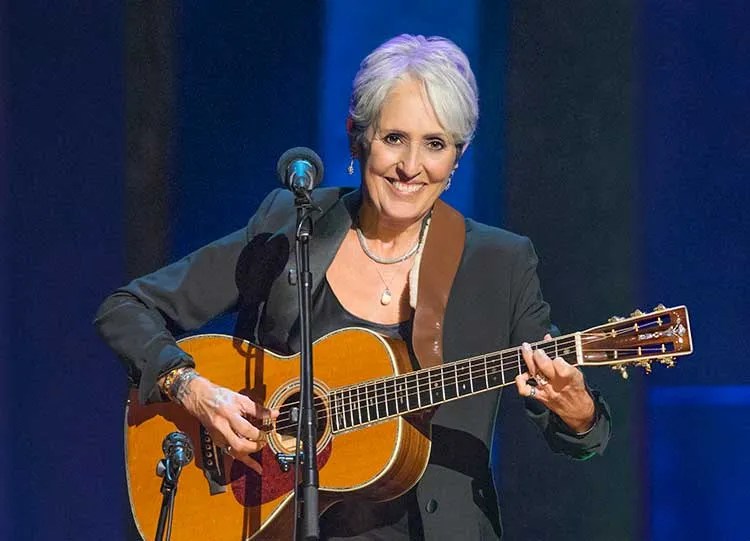

Roots Guitarist and Educator Happy Traum Teaches a Few Songs from His Storied Career

In 1954, when Happy Traum was an art student at New York City’s High School of Music and Art, some classmates invited him to go see a Pete Seeger concert. At 16, Traum was not really familiar with Seeger or active in music, but he tagged along—and was stunned by what he discovered.

“The whole idea of hearing somebody on a stage by himself, with an instrument, was the antithesis of the pop music I was listening to on the radio, where you couldn’t do that yourself,” Traum recalls. “Here was a guy who told us, pretty much, ‘You could do this, too. You just stand here and play some chords and sing songs.’ And Pete was singing about peace and freedom and civil rights—that was something I felt but didn’t know you could express. It just blew open my head. I had to go get a guitar and start learning how to play.”

After that encounter with the legendary folksinger, Traum not only devoted himself to the guitar, he also embraced Seeger’s lifelong mission to help others make music themselves. So, along with embarking on a career as a performer, Traum became a guitar teacher—and he ultimately made a signal contribution to modern music instruction by starting Homespun Tapes with his wife, Jane, in 1967. From reel-to-reels to cassettes, VHS tapes, DVDs, and online video, Homespun has released some 700 lessons by many luminaries of American roots music—including Tony Rice, Norman Blake, Jorma Kaukonen, Chris Thile, Jerry Douglas, and Seeger himself, with a video version of his pioneering book How to Play the Five-String Banjo.

On a balmy summer afternoon, I visit Happy in Woodstock, New York, at the house he and Jane began building in 1970 in an old farm field, living in a tent with their kids for a few months during the construction. More than 50 years later, Happy remains a pillar of the Woodstock music scene, alongside friends and collaborators such as John Sebastian, Larry Campbell, and Cindy Cashdollar. “It’s still a thriving music community,” Traum says. “I feel like an elder statesman in a funny way.”

I’ve known Traum since the beginning of Acoustic Guitar, interviewed him multiple times, and worked with him on my own Homespun video series teaching acoustic arrangements of Grateful Dead songs. Whether he is teaching in a workshop, in print, or on screen, I am always struck by his gift for breaking complex technique into clear steps, with a low-key, encouraging manner that makes the whole process accessible and fun.

At 83, Traum is remarkably youthful—still playing concerts and teaching at music camps like Richard Thompson’s Frets and Refrains and Jorma Kaukonen’s Fur Peace Ranch, in addition to his ongoing work with Homespun. Never caught up in the music business rat race, Traum always seems genuinely to play music—as suggested by the title of his most recent album—Just for the Love of It. And he is still creating content for Homespun, such as a new lesson on Woody Guthrie songs, as well as nearing completion of another solo album.

Sitting in his sunroom with his Santa Cruz HT/13, a brand-new signature model with a gorgeous redwood top and tone to match, Traum shares a few stories and songs from across the years. What follows is a retrospective of Traum’s life in music as captured by six songs.

Brownie’s Blues

Just a few years after first hearing Pete Seeger, Traum made another life-changing musical connection. He was a student at NYU—then with its main campus in the Bronx, where he grew up—and a friend gave him the Folkways LP Brownie McGhee Blues, featuring the great blues guitarist solo rather than with his duo partner Sonny Terry on harmonica. Traum obsessed over the music and learned that McGhee lived in New York, so he looked up the bluesman in the phone book and called to ask about taking lessons.

At McGhee’s apartment on 125th Street, Traum got a deep immersion in a style of Piedmont blues fingerpicking that’s still at the core of the music he plays today. In these informal lessons, he recalls, “We’d just start playing together. If I saw something he was doing that I didn’t know, I’d stop him and say, ‘What was that?’ and he’d show it to me. He was very patient.”

One of McGhee’s core lessons was the importance of keeping steady time with the thumb. McGhee played mostly monotonic bass—thumping on a single bass note under each chord—with a thumbpick, while covering the higher strings with two metal fingerpicks. “He would stress to keep your thumb and your foot going at the same time,” Traum says. “I do that to this day.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Example 1 shows a 12-bar blues pattern that McGhee taught, and used in “Good Morning Blues” and other songs. Play either a monotonic bass, as notated, or double up the bass notes with a shuffle rhythm (see the video for a demo). On top, play single notes that outline the E7, A7, and B7 chords—McGhee’s term for this was “breaking up the chords.” Interestingly, McGhee did not typically play a B bass note under the B7 chord; he just continued the six-string E on the bottom (as in measure 9), muted so it didn’t clash too much with the harmony.

Traum remained friends with McGhee well past his years of lessons. One of Happy’s first dates with his future wife, Jane, in fact, was driving McGhee and Sonny Terry circa 1958 up to Bard College, where Happy opened for the duo. He also profiled his blues mentor in one of his early books, Guitar Styles of Brownie McGhee, published in 1971.

A New World of Song

Beyond lessons with McGhee, the place where Traum furthered his roots music education was the buzzing folk scene centered around Greenwich Village’s Washington Square Park. “People like Tom Paley [of the New Lost City Ramblers] would show me fingerpicking,” Traum recalls. “Or Dave Van Ronk would be sitting there playing, and I’d be figuring out what he was doing.”

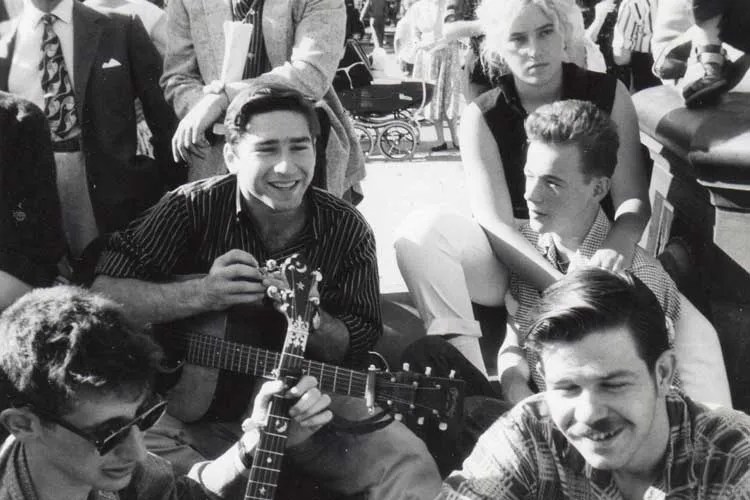

The New World Singers, (clockwise from top left): Happy Traum, Delores Dixon, Bob Cohen, and Gil Turner. Photo by Maurice Seymour

One prominent musician in the Village was Gil Turner, a Pete Seeger disciple and banjo picker whom Traum met at a protest march. Turner started a group called the New World Singers with the gospel singer Delores Dixon and rhythm guitarist Bob Cohen, and he invited Traum to join as lead guitarist. Along with gigs at clubs like Gerde’s Folk City and the Bitter End, Traum joined his bandmates in 1963 for his first time in a professional recording studio. A benefit for Broadside magazine, the session was an extraordinary gathering of political songwriters, including Seeger, Phil Ochs, Peter La Farge, Mark Spoelstra, the Freedom Singers, and a young guy billed on the record as Blind Boy Grunt—soon to be rather well known as Bob Dylan. (He’d just signed with Columbia so couldn’t use his name.)

“It was quite a group, all in one studio, all at the same time,” says Traum. “We would just get up in front of a microphone, one take, sing the song, you’re done.” The New World Singers recorded three songs, most famously laying down the first-ever recording of “Blowin’ in the Wind” while the songwriter listened. Another Dylan debut that day was “I Will Not Go Down Under the Ground (Let Me Die in My Footsteps),” which Traum sang while Dylan backed him on guitar and harmony vocals. Both tracks are available on the Folkways reissue Broadside Ballads, Vol. 1.

On “Blowin’ in the Wind,” Traum played an intro similar to Example 2, based on the refrain. Use C shapes, capoed at the second fret to sound in D, and alternate double-stops on the fourth and second strings with the open third string. Play fingerstyle, or hybrid style with a flatpick and your middle finger. Traum frets the F bass note in measure 3 with his thumb, but grabbing that note with the first finger works fine, too.

Fingerpicking Masters

During his time with the New World Singers, Traum continued to dig deeper into his true passion: traditional folk and blues fingerpicking. That was the topic of his first lesson book, Fingerpicking Styles for Guitar (1965), which dug into songs and arrangements by seminal players such as Elizabeth Cotten, Doc Watson, Merle Travis, and Mississippi John Hurt.

Like many other guitarists of the folk revival, Traum was inspired by the melodic picking of John Hurt, and he had the chance to meet the gentle guitar master at the Village’s Gaslight Café, in the tiny kitchen that served as backstage.

“The amazing thing about John Hurt to me is that I play maybe a half dozen of his songs, and every time I go back and actually listen to him, I realize—I thought I was doing it like he was, but it’s not even close,” says Traum. “I don’t know what it is. Maybe it’s the fact that his fingers were all callused from doing hard work all his life. But he had some special thing.”

A few years after Hurt passed away in 1966, Traum wrote the tribute song “Mississippi John,” and eventually recorded it with his brother, Artie, for the 1975 album Hard Times in the Country. “Mississippi John” remains in Happy’s repertoire; on YouTube you can find a 2014 live version with Traum accompanied by jug band maestro Jim Kweskin. Traum fingerpicks in a classic Hurt style, using C shapes (capo 4 to sound in E) with an alternating bass. Example 3 shows the verse accompaniment (as you’ll see in the video, he adds some variations in the second pass) and the instrumental interlude, which is based on Hurt’s version of “My Creole Belle.”

As with the earlier Brownie McGhee blues example, the thumb is the key. “When I’m doing those kinds of songs, my style is very much that relentlessly steady bass,” Traum says. “The only time I vary from that is if I’m doing a ballad with more of a flowing feel.”

Jamming with Bob Dylan

In 1966, Happy and Jane Traum moved upstate from New York City to spend a summer in Woodstock, a hub for artists long before the famous festival made it a hippie/tourist mecca. As it happened, another recent arrival in Woodstock was Bob Dylan, who was off the road and recuperating from a motorcycle accident. So Dylan and Traum reconnected, and after the Traums moved to Woodstock permanently in 1967, they often played music together informally.

This friendship resulted in Dylan inviting Traum to play bass in a memorably chaotic recording session in 1971 with beat poet Allen Ginsberg that included the multi-instrumentalists David Amram and Jon Sholle, a Buddhist monk, and, as Traum recalls, poet Gregory Corso “running around, raising a ruckus.”

That same year Dylan called with another invitation—to bring a bass, guitar, and banjo down to the city for a duo session. “He wanted to record some songs that he had written but other people had had hits with. Bob’s idea was whatever we would do sitting around the living room, just jamming, was what he wanted to put on this record.”

Schlepping his instruments down to the city on the bus, Traum had no idea what he’d be playing, so everything was off the cuff, in one or two takes. In the end he and Dylan recorded four songs. Traum played banjo and bass on “You Ain’t Going Nowhere” (which had been covered by the Byrds in 1968), and he added guitar to “I Shall Be Released” (featured on The Band’s debut album) and “Crash on the Levee (Down in the Flood)”; Dylan’s and Traum’s duets of these three songs appeared on Dylan’s Greatest Hits, Vol. II. Traum figured that the fourth song they recorded, “Only a Hobo” (which Dylan actually had recorded in the earlier Broadsides session as well), was lost or rejected. But 20 years later, it unexpectedly surfaced on Dylan’s The Bootleg Series, Vols. 1–3.

ADVERTISEMENT

Example 4 shows the type of part thatTraum layered on top of Dylan’s rhythm guitar on “I Shall Be Released.”While Dylan played out of G shapes with a capo at the second fret (to sound in A), Traum added figures up the neck. On the C#m and Bm in measures 5 and 6, roll the chords by picking the strings quickly in sequence, low to high, with your thumb and fingers.

Dylan’s music continues to be a touchstone for Traum. He’s created lessons for Homespun with his own fingerpicking arrangements of Dylan songs, and on his 2015 album Just for the Love of It, he revisited “Down in the Flood,” trading solos with his guitarist son, Adam Traum—now a performer in his own right as well as a video producer/editor for Homespun.

Tapping into Tradition

A major part of Traum’s musical life was collaborating with his younger brother, Artie, from the late ’60s right up until Artie passed away in 2008. The two had sibling musical chemistry, for sure, but also very different styles and interests.

“He was a very talented guitar player and songwriter,” Happy says of Artie. “He was always more adventurous musically than I was. I was always pretty strictly traditional and stuck with blues, folk songs, and ballads. He started on banjo, but when he started playing guitar, he actually took a couple of lessons with Jim Hall, the great jazz artist. So when he was a teenager, he was already stretching out into jazz stuff.” In the ’90s and early 2000s, Artie found considerable success with instrumental smooth jazz on guitar.

Even with his jazz leanings, Artie was “very well grounded in the traditional stuff,” Happy adds. “When we played together, he fell into what I did more than I fell into what he did.”

The duo’s first album, Happy and Artie Traum, released by Capitol in 1970, closed with the song “Golden Bird,” which sounds like an old mountain ballad but actually is a Happy original that’s been covered by a number of other artists—notably fellow Woodstock musician Levon Helm, in a haunting performance on his final studio album, Electric Dirt.

“Golden Bird” dates from when Happy had recently moved to Woodstock and was first starting to put songs together with Artie. “I was living right up the hill,” Happy says. “I had Doc Watson in mind when I wrote the song, thinking, ‘What kind of a song would he like?’ And then I came up with that kind of folk tale.”

On the original recording of “Golden Bird,” Happy played clawhammer banjo while Artie flatpicked the guitar; in 1978, Happy revisited the song on the solo album American Stranger with his own flatpicking guitar. Nowadays, though, he plays fingerstyle exclusively and has arranged “Golden Bird” in dropped-D tuning, as shown in Example 5.

The song is in the key of G, and while singing he plays a boom-chuck-type pattern, picking bass notes with the thumbpick and strumming the treble strings with his fingers. The notation shows a Carter-style instrumental break. Pick the melody with your thumb and add touches of the chords with your fingers, especially on beats 2 and 4.

If you’re familiar with Helm’s take on “Golden Bird,” by the way, it’s interesting to note that not only did Helm slow the song way down, but his arrangement does not use the V chord at the end of the progression. Instead, he went straight back to the I. In Traum’s key, G, that would mean substituting a G for the D in the last two bars—a very different, starker sound.

Timeless Melodies

Although Traum is proud of songs like “Golden Bird,” songwriting has never been his focus—he estimates he’s got around eight or ten original songs in his repertoire, plus some co-writes with Artie. In the writing process, Happy says, “I keep getting a few lines into a song and then I think, ‘Wait a minute. There are so many great songs out there. Why do they need me to do this?’ I don’t have that drive.”

What does drive him is arranging great songs for guitar. One lovely example is his take on “The Water Is Wide,” played in dropped-D tuning and featured on Just for the Love of It. His video demo for this lesson isn’t precisely the same as the album track; in performance, he may follow the general shape of a worked-out arrangement, but the details vary each time. (A complete transcription of his album version is available from Homespun.)

ADVERTISEMENT

Traum is a big fan of dropped D, for songs not just in D but in G, A, and other keys. One of the obvious draws of the tuning is the octave D notes on the open sixth and fourth strings—great for alternating bass. “And then when you move up the neck, you can use all six strings,” he says. “Even in E, when you’re tuned to standard, if you go up the neck, you have your bass E but you don’t have the [open] fifth and fourth strings.”

Example 6 shows one instrumental pass through “The Water Is Wide.” The picking style, he says, is “the antithesis of the steady thumb,” with bass notes often ringing out for two beats or skipping beats entirely. In measures 3, 6, and 9, shift up to fifth position, taking advantage of the open-string bass notes. Bars 6, 8 and 14 each include a quarter-note triplet, adding a nice flow to the ascending melody lines.

[Ed. Note: For an additional dropped-D guitar arrangement by Traum, see the transcription of “Worried Blues”.]

Sharing the Music

Toward the end of my visit, Traum opens his iPad and shares some rough mixes from his in-progress solo album. He has a long history with many of the songs, including Brownie McGhee’s “Living with the Blues”; the traditional ballad “When First Unto This Country”; Blind Willie McTell’s loping blues “In the Wee Midnight Hour”; his own “Love Song to a Girl in an Old Photograph,” written a half century ago; and even a Broadway tune—a solo guitar arrangement of “How Are Things in Glocca Morra?” from Finian’s Rainbow. With guests like Larry Campbell, Bruce Molsky, Geoff Muldaur, John Sebastian, and Cindy Cashdollar, the album will be, as always, a reflection of Traum’s musical friendships and community.

No doubt when the album comes out, it’ll also be accompanied by lessons to help other guitarists play these great songs. Traum’s desire to share his discoveries and passions doesn’t fade.

“If I’m learning some new song or some new technique on the guitar,” he says, “somewhere in the back of my mind I’m thinking, ‘Now how can I show this to other people? How can I convey to other people the fun I’m having with this?’ Even now, at this advanced age, I’m still thinking in those terms.”

ADVERTISEMENT

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2021 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.

Many of the teachers who contribute lessons to Acoustic Guitar also offer private or group instruction, in-person or virtually. Check out our Acoustic Guitar Teacher Directory to learn more!