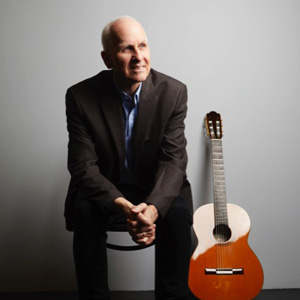

Passion and Fire: How Russian-Born Virtuoso Grisha Goryachev Became a Flamenco Guitar Master

At first glance, Grisha Goryachev seems an unlikely torch bearer for flamenco guitar. He was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1977, descended from ancestors with Russian and Ukrainian lines. His forebears lived far from Andalusia, where flamenco music developed among the Romani people who migrated from India to settle in southern Spain in the ninth century. Goryachev’s heritage notwithstanding, those hearing his extraordinarily fiery playing might assume he has Romani bloodlines or that he polished his skills playing the stages of Granada. His emergence as a flamenco phenom hailing from Russia underscores the maxim that music is a universal language with dialects that resonate internationally.

Those attending Goryachev’s Boston GuitarFest concert last June felt the fire in his stunning renditions of forms by Paco de Lucía, Vincente Amigo, Gerardo Nuñez, and others. His opening piece, “Zapateado en Re” by Sabicas, interspersed rapid-fire tremolo passages, blindingly fast rasgueados, picado runs, and arpeggios among the melodic sections. He followed up with “Malegueña de Lecuona,” Paco de Lucia’s take on the Malegueña movement of a piano work by Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona. Italso included plenty of fireworks.

Throughout the 13 numbers he played, Goryachev explored an array of flamenco dance forms such as fandango, bulerías, guajira, and alegrías, embodied in compositions he regards as masterpieces created by historic and contemporary flamenco artists. His enthusiastic audience—spontaneously shouting “¡Olé!”—was feeling the heat and passion Goryachev radiated in the music he loves.

In a wide-ranging phone interview a few days after his concert, Goryachev discussed his early training, interactions with Paco de Lucía, arrival in America, and approach to performing.

Family Lines

Goryachev’s training followed the old-world model of a father passing on skills to a son. He started learning classical guitar in his grade-school years under the tutelage of his father, Dmitry Goryachev, an ardent Andrés Segovia devotee and master teacher. The younger Goryachev’s early embrace of the esthetics and techniques of classical guitar shaped the evolution of his burnished sound and musical sensibilities. His father prioritized teaching the movements of the hands and fingers over sight-reading skills at first.

In learning classical pieces, Goryachev was immediately drawn to the Spanish repertoire. Inspiration for his future path came into focus when at eight he attended his first flamenco concert, a transformative experience affording a glimpse of breathtaking, exotic musical vistas. “In 1986, Paco de Lucía played a concert in St. Petersburg,” recalls Goryachev. “Hearing him for the first time and feeling the energy in his playing completely blew my mind. I came home and begged my father to teach me how to play like that.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The elder Goryachev was up for this daunting challenge, but life in the Soviet Union posed obstacles to obtaining flamenco recordings and method books. One of Dmitry’s former teachers, Abraham Brustein, a collector of flamenco recordings and sheet music, was a crucial connection. “My father’s friend had contacts outside of the Soviet Union and had acquired quite a collection,” Goryachev says. “Through him, we got flamenco recordings and photocopies of the guitar method by Juan Martin. The recordings were not originals; they were tapes made from tapes of tapes.”

Together, father and son set about exploring the technical foundations and traditional forms of flamenco guitar. Dmitry would absorb the material in Martin’s El Arte Flamenco de la Guitarra and present it to Grisha. The elder Goryachev had a unique and effective approach to teaching technique. Rather than demonstrating specific hand and finger movements on his guitar, he would stand over his student’s shoulder and use his hand to move the fingers on the strings. This conveyed a tactile sensation of how a technique should feel when properly executed.

Goryachev attributes his seemingly limitless facility on the guitar to learning the basics in this manner. It was also a boon that he started out learning classical pieces by watching his father play them. After he learned to read music and understood notation, Goryachev and his father began transcribing the music of the top flamenco players. Back then, there were no published editions of the music of Sabicas, Rafael Riqueni, de Lucía, and others. The only option for learning the music was repeatedly playing along with the recording and memorizing it.

Martin’s method book offered a thorough overview of flamenco techniques like rasgueado strumming, tremolo, ligados (slurs), golpe (tapping the guitar’s top), as well as compás (rhythmic structure of traditional forms such as farruca, soleá, seguriyas, and sevillanas), and much more. After spending a year immersed in Martin’s method, Goryachev had mastered all of the material and began giving public concerts.

Prodigious Progress

At 11, Goryachev could keep up with his hero Paco de Lucía as he played along with some recorded selections. By the time he was 13, his technique was quite advanced. One distinctive feature of Goryachev’s playing is that, even while playing his fastest, he has never sacrificed sound quality for speed. “Tone was always a big topic for my father and me,” he says.

Gaining a reputation as a prodigy, Goryachev began playing solo flamenco concerts in Russia and Europe in his teen years. His programs featured his transcribed coplas (song forms) of historic flamenco masters like Sabicas and contemporary players like de Lucía. The opportunity of a lifetime came when Goryachev was invited to play at de Lucía’s Madrid home in 1994. The master guitarist offered him positive feedback and advice. He told Goryachev to move to Spain if he wanted to learn more about flamenco. Though Goryachev never did so, the two guitarists stayed in touch.

As the end of Goryachev’s public school years approached, he pondered his future. “I was getting a lot of pushback from old-school classical guitarists in the Soviet Union who felt that flamenco was salon music, a circus for show-offs, and that it had no artistic merit,” he shares. “No conservatory or music college there would accept me as a flamenco guitarist. Back then, there was this animosity between classical and flamenco players—maybe because of Segovia’s stance on flamenco.” (The maestro allegedly asserted that classical and flamenco guitar were like opposite sides of the mountain that never see each other.)

Visiting America in 1995 on a tourist visa, Goryachev felt compelled to stay. He applied for a green card upon learning that one avenue for obtaining that credential was to be recognized as a person with extraordinary abilities. He reached out to de Lucía to ask if he would write a letter of recommendation on his behalf. “Paco communicated with my lawyer and submitted a letter saying good things about me to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services,” Goryachev says, a bit self-consciously. “As soon as they got the letter, I was granted permanent residency status.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The ripple effects from de Lucía’s kind gesture impacted the entire Goryachev family, who dreamed of coming to America. In a tremendous stroke of luck, Dmitry; his wife, Natalia; and Grisha’s older brother, Sergey, entered the green card lottery and won. In 1997, the family joined Grisha in Boston.

Goryachev was accepted at New England Conservatory and began classical studies with virtuoso guitarist and professor Eliot Fisk in 2000. He ultimately completed his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctor of musical arts degrees under Fisk’s mentorship. “I owe a great deal to Eliot,” Goryachev reflects. “My father helped me develop my technique, so I didn’t need much correction there. One thing Eliot did was open me up. I was a very shy person when I came to him—timid about expression. Even though music meant a lot to me, I was afraid to express it in a way that others would feel my emotion. Eliot completely broke my chains.”

Coursework in music history, theory, and composition of Western classical music as well as Indian and Turkish music greatly expanded Goryachev’s horizons. “It’s easy to just get stuck in guitar music,” he muses. “I started appreciating things that the ear can’t initially make sense of and started looking at musical design and compositional elements. Then I could start hearing them.”

In the Moment

Goryachev continues to transcribe music by flamenco giants. He’s fastidious about learning everything as played on the record, deciphering the fingerings and even the direction of the strumming. “After that, I relax a bit and start playing the piece in my own way. Then things that I could improvise come to mind,” he relates. “When I perform, I do what feels right in the moment without making the composition into something completely different. I want others to experience what it’s like to hear the original life in this music.”

YouTube videos of Goryachev abound, yet the guitarist’s discography lists only two albums. His ambitious 2006 debut, Alma Flamenco, on which he plays a classical guitar, features works by Spanish composer Isaac Albéniz alongside pieces of Sabicas and Paco de Lucía. On Homenaje a Sabicas from 2007, Goryachev plays 11 Sabicas originals on a flamenco guitar. Goryachev has considered making a new album, but has not yet blocked out a window of time for it owing to his rigorous practice schedule and concert preparation, to which he devotes seven hours daily.

“I spend about one third of my practice time on specific elements of technique: scales, arpeggios, rasgueados, and more,” says Goryachev. “But if you do the same routine all the time, you’ll check out mentally. You need variety, lots of exercises for every technique. I’ll use one set of them for a few days then switch to others before returning to a previous set.”

Today, Goryachev is among a small number of performers preserving the legacy of highly charged solo flamenco guitar concerts. Playing throughout the United States and in 30 countries thus far, he imbues each performance with maximum spontaneity.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Eliot taught me to take chances onstage,” Goryachev shares. “It could end up being my best or worst concert because I took chances—maybe I nail it, maybe I fail. What the audience feels, though, is your honesty and energy. In every concert, I give my all and take all the chances I need to.”

What He Plays

Grisha Goryachev plays a 2017 Lester DeVoe with a European spruce top, rare satinwood back and sides, and a neck scale of 655mm. He uses medium-gauge Galli titanium treble strings and Savarez Cantiga Premium high-tension basses. Goryachev also uses Guitar Player Nails to meet the rigors of flamenco playing.

—MS

Eliot Fisk on Learning from His Student

I was privileged to work with Grisha for about nine years, from when he started his bachelor’s degree at NEC through his DMA. I’ve occasionally had students who came to me already incredibly advanced and fully formed as artists, but Grisha was in a class by himself. He remains a towering instrumental genius with an incredible ear and a really unexplainable talent. Many simply view him as someone who plays fast. Well, Grisha is fast, but there’s real musical genius mixed in with his technical genius.

ADVERTISEMENT

He has been very generous in crediting me for making a difference in his life, but my impression was mostly that I was learning more from him than he was from me. Once you reach a certain age, you realize that we’re here just for a short time. You pray for the opportunity to do some good before you turn into a bag of white ashes. That remains my aspiration. Perhaps in our work together, I contributed a little bit. More important still, despite his almost intimidating talent, Grisha is a person who gives hope to me and to anyone else who meets him in person. I am thrilled by his well-deserved success! —As told to Mark Small

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2025 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.