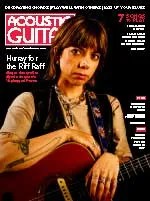

Hurray for the Riff Raff’s Alynda Segarra Looks Ahead, and Reconnects with Acoustic Guitar, on ‘The Past Is Still Alive’

Alynda Segarra, the Bronx-bred, New Orleans–based singer-songwriter who leads Hurray for the Riff Raff, sounds invigorated as the band prepares to get back in the van for yet another lengthy West Coast trek. Today it’ll be about eight hours, from Sacramento to San Diego. Segarra and crew have been rolling across the U.S. (with a quick stop in Canada) for more than a month, playing shows in support of their eighth studio album, The Past Is Still Alive (Nonesuch). But with two weeks of travel still on the calendar, the going doesn’t appear to have gotten even close to tough.

“It’s been amazing,” Segarra says. “I’ve never had tours like this. I feel like people are connecting to this record in a way that I just haven’t experienced before. The energy is heightened. People are singing along and seem really in it.”

What might the reason for this be? “Well, I think it’s my best work for sure,” says Segarra. “I’ve gotten a grasp on my own language and my own version of storytelling. But I also think we’re going through a very interesting time collectively, and the topics of grief and memory and time passing are really touching people right now.”

Case in point: “Ogallala,” the country-tinged climax of The Past Is Still Alive. Over a slow, deliberate 4/4 beat, a pedal steel guitar traces mournful paths around the stoic braying of two saxophones (baritone and tenor), and a dust-bowl cloud of reverb rises as Segarra sings, with an intimacy that half conceals the underlying drama:

I used to think I was born

Into the wrong generation

But now I know

I made it right on time

To watch the world burn

In our current era of climate gloom, political uncertainty, and general post-pandemic pessimism, these words ring out like an anthem.

“Every night, people are waiting for the release of that line,” Segarra confirms. “Of course it’s not celebratory, but there’s a relief in talking about it, in naming this fear that’s hanging over all of our heads.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Another distinguishing feature of The Past Is Still Alive is Segarra’s return to the acoustic guitar, a key ingredient of much of Hurray for the Riff Raff’s past work that largely went missing on 2022’s electronically focused Life on Earth. As the following interview shows, this new integration of the band’s American folk roots with a more sophisticated level of songcraft was spurred in part by a creative rut—which Segarra broke out of by moving a few fingers around.

On the standard edition of Life on Earth, acoustic guitars were few and far between, but the deluxe version of that album featured acoustic versions of several tracks. This seemed to suggest that the songs had been written in a “traditional” way and then transformed in the studio. But was that actually the case?

Not for all of them. Some of them I couldn’t even play on guitar, even though they’re probably extremely simple. But songs like “Precious Cargo” I wrote to a beat. I wanted to play around with different song structures and see what would happen if I wrote in a more rhythmic way. I was listening to a lot of [R&B artist] Frank Ocean, and I thought it would be good for my songwriting to free myself of my limitations as a guitar player. But some of the Life on Earth songs, like “Saga” and “Pointed at the Sun,” are very much guitar songs. So it’s kind of split.

What changed in your songwriting approach for The Past Is Still Alive?

I’d had some time away from the guitar, where I didn’t feel as limited, and I was having conversations with my guitar-playing friends where I’d be like, “What do you do when you feel stuck with the instrument?” ’cause I felt my limitations were blocking me. And my friends gave me good advice, like, “Play a chord and then just take a finger off one fret.” You do that and then you’re like, “What is that now?”

Obviously, my strong suit isn’t being an incredible guitar player. I love holding down the rhythm, and I like the song structure to be pretty simple and the chords to be simple, and then I run off the rails with the lyrics or the melody. But that advice was helpful. It brought me to different places. “Colossus of Roads” and “The World Is Dangerous” are great examples of me taking simple chords but changing one note and suddenly being like, “Oh, wow! Now it’s a lot darker; now it’s a lot more mysterious.”

Another trick guitar-playing songwriters often use to view the instrument afresh is to change its tuning. Did you do any of that?

On “Snake Plant” I did. That’s in open C. And the album version of “Dynamo” is in open D. Live, I’m not doing it that way. But “Snake Plant” in open C really hits different. That’s an example of a song where I just wanted two chords, back and forth, and we hit the ground running and keep running. And when you take it to an open tuning, everything is possible. That’s where the magic is. Suddenly you’re just following what you think sounds good.

Even a song like “Alibi”—I originally wrote that as a fingerpicking song, and the tempo was very down. I was playing chords that I didn’t even know, just going up the neck and playing around. I brought it to [producer] Brad [Cook] like that, and he said, “I hear this being more anthemic and up-tempo.” At the time I thought he was crazy, but now when I hear it, I can’t imagine it any other way.

ADVERTISEMENT

When you started Hurray for the Riff Raff in 2007, you were a banjo player. On the first two albums, 2008’s It Don’t Mean I Don’t Love You and 2010’s Young Blood Blues, you didn’t play guitar at all. Was that because you hadn’t gotten around to the guitar yet, or was it an aesthetic choice?

Banjo was the instrument that I felt strongest on. Also, I was coming from New Orleans, and guitars weren’t what most people were playing there. More people were playing instruments that you use in traditional jazz or early American folk music. I was doing a lot of accompanying fiddle players on old Appalachian folk tunes and chunking on chords in traditional jazz bands. But then, as I got more and more obsessed with songwriting, I felt like the music [I was writing] was becoming so genred, so niche [because of the banjo]. You know, my plan is eventually to re-record some of my very early songs. They’re great at their heart, but the recordings are too stuck in a certain style.

It was hard to make that changeover to guitar, kind of like growing pains, but I was lucky to have friends. I’ve been playing for a long time at the Jalopy Theatre in Brooklyn. They do something called Roots n’ Ruckus every week, where folk musicians come in and you can play a couple of songs, and they pass the hat for you. And there’s an amazing group of guitar players there who were so helpful to me.

The first place I went was to Carter Family recordings to learn about Maybelle [Carter]’s flatpicking—and then, of course, Elizabeth Cotten, trying to learn some fingerpicking techniques from those recordings. But I also had a lot of friends that were able to guide me and show me different things.

What was so hard about making the changeover to guitar from banjo?

There’s a different culture around the guitar, which I think, gratefully, is changing. But especially at that time, I felt like banjo was less open to criticism or cynicism or sexism. All the isms. You pick up a banjo and people are like, “Oh, that’s cool!” Then you take out a guitar and they’re like, “You’re out of tune!” and “That’s not how you play that!” As a young kid playing out in public, I’d get that kind of reaction and it was just like, “Damn, this is rough. I’m not trying to blow anybody away with my guitar playing—I’m just trying to accompany myself!” But I do think that things have been changing in this really great way. There are so many amazing guitarists out there now that are not, you know, men. And, of course, back then I was playing in dive bars; it wasn’t anywhere that was distinguished. But I learned how to tune—that’s for freakin’ sure [laughs].

ADVERTISEMENT

Your road to country/folk/Americana—or whatever you want to call the music you make now—began with punk rock, right?

Totally. I think so much about Lou Reed, because the Velvet Underground is at the root of everything I do. It’s also just kind of in my DNA, being a New York City kid. And I think about how Lou Reed was a songwriter before the Velvet Underground, coming up with, like, doo-wop songs. There’s this route of coming from classic American music, folk and blues and early rock ’n’ roll, and then you change it, you put yourself in it, and it grows.

If the Velvet Underground was the root for you, what were the branches?

Well, Johnny Cash was huge. I always say that Johnny Cash is the gateway drug from punk to country, because he’ll lead you to everybody. He’s such a rebel, and he was so independently minded—his spirit of being for the underdog really resonates with punks. So Johnny Cash led me to Lead Belly, who led me to Woody Guthrie and to Alan Lomax’s field recordings.

I started getting into this idea of how everybody has a song. It wasn’t even so much about finding artists, it was about finding people who had family songs or work songs. That was really exciting to me, especially moving to the deep South and learning about resistance songs—this idea that the people built this. It’s not about an industry, it’s not about stars, it’s about regular working people having songs that are worth being recorded and worth being learned. All of that formed my philosophy about songwriting. I mean, I love having a band and I love having listeners, but sometimes I just feel like telling them, “You can do this too, you know?” Maybe it won’t be as a professional thing, but everybody should write songs and sing songs. It’s part of our right, as human beings.

ADVERTISEMENT

Riff (Raff) Makers

A 1957 Gibson J-50 and a late-’50s blonde Kay archtop have long been Segarra’s favorite guitars, but they’re now retired from road service, replaced by an early ’90s Guild (for standard-tuned songs) and a new Fender Paramount (for open-tuned ones). For live work, Segarra uses L.R. Baggs M1 pickups and an Electro-Harmonix Holy Stain multi-effects pedal. The latter has “changed the game for me,” Segarra says. “I can have a little bit of reverb and really mess with the tone, make it more bassy.”

Segarra also recently picked up an all-mahogany Martin 00-15M for fingerpicking, which you can hear on The Past Is Still Alive’s “Buffalo.” That guitar gets strung with D’Addario Silk & Steels, while the others take either John Pearse or Martin; gauge is standard light (.012 on top) for everything. —MR

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2024 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.