How to Shop for a Used Guitar

When shopping for your next guitar, there are plenty of reasons to consider buying something pre-owned. If you’re shopping for value, you stand to get more for your money in the category of used. And, of course, if you’re in the market for a vintage sound and look, there’s no substitute for the real thing. With a few tricks, you can feel confident heading out into the world of used-guitar shopping.

In this three-part series, I’ll give you some perspective on how to decide what you’re looking for, how to find it, and how to feel good about the money you’ll spend:

Part One: Let’s talk about where to shop for guitars and how to decide what you’re looking for.

Part Two: Let’s talk about buying a used guitar that needs repairs—as so many of them do. We’ll cover what tools are useful in inspecting a guitar, what repairs are easily handled, and some common issues to look out for.

Part Three: Let’s talk about checking out what’s inside the box—braces, bridge plate—to help you shop for a hearty guitar. I’ll also cover how to tell if a guitar has a healthy neck angle—and whether you might need to commission a neck reset for it!

So, how do you decide what you’re shopping for? Well, what are you interested in? Are you a rank beginner whose only requirement is an instrument that’s playable? Or do you have a crush on a specific guitar, like a 1940s Gibson J-45 with a banner headstock? I would suggest starting with an idea of what you would love to find, and playing as many instruments as possible. This will help you know what feels natural in your hands—and pleasing to your ears—as well as what you can expect to pay. Don’t rush the process. You’ll learn a lot just by checking around and seeing what’s out there—and if needed, adjusting your idea of what you’re shopping for.

Where should you look for used guitars? You can visit a vintage guitar dealer, try to find a private sale, or bid in an auction. Of course, getting a guitar in your hands and playing it is ideal. This will give you a chance to see whether you really like it, and whether it’s a good example of its model. For instance, two 1965 Martin D-18s won’t feel or sound exactly the same.

The internet is a great resource, and you’ll find lots for sale on eBay, Reverb, and the like, but you’ll want to make sure that the seller has good communication skills and allows for returns if the guitar is not as promised or if you simply don’t like it. Wherever you’re shopping, you’ll want to know how to inspect a used or vintage guitar, and I’ll talk more about that process in the next installment.

ADVERTISEMENT

By the way, you can pretty much count on not getting a one-off, insanely good deal. We’ve all heard the stories, but those days are over thanks to the internet. With a little time, any seller can figure out fair market value for their instrument, so plan on paying a reasonable and comparable amount for that guitar in your area.

Don’t forget—you will likely need to put some money into repairing an old guitar, so figure that into your budget. (I’ll go into more detail regarding this later in this series.) To start with, most older guitars will need at least a setup—a truss-rod tweak and a saddle-height or nut-slot adjustment—so set aside at least $65 for that. Many instruments will need a lot more, like crack repairs, a neck reset, or a re-fret. If you buy a guitar in a private sale you will generally get the best deal, but consider why it’s being sold. Does it need work that the owner doesn’t want to bother with or doesn’t even know about?

This is one of the advantages of shopping at a vintage guitar dealer—they usually have a repair department. It’s true that there will be a markup at a vintage dealer, but it’s not a mystery what you’re paying for. They have sourced a guitar they thought was interesting and marketable, and fixed it as needed, because a piece that’s in good shape commands a higher price than one requiring restoration.

A dealer should be upfront with you about what they know about a guitar, including what work it’s had done or might still need. Here is where you’ll go with your gut instinct. Have you heard good things about a particular dealer? Do you like the way they answer your questions, and do you feel trusting of them? You should! Their business depends on you feeling good about the transaction. For a certain kind of shopper, one with a little more to spend and who is looking for some assurance along with their new old guitar, a vintage dealer can be a good choice.

In fact, simply going to visit a shop, whether it’s a vintage dealer or a neighborhood music store, really should be in your plans. Don’t just sit at home and look online! Talking to people who know a lot about guitars is so valuable. For example, say you love an older small-bodied mahogany Martin, like a 00-15, but can’t find one you can afford. A dealer in a brick-and-mortar store can help suggest a wonderful substitute, like a Guild M-20, the guitar that Nick Drake famously played.

So you’ve been shopping for your new favorite old guitar, and you’ve done everything right: You’ve got an idea in mind of what kind of guitar you’re looking for, you did some research to get a feel for what things cost in your area, and you’ve started to look at guitars that could work for you. Here are some techniques to help you determine what kind of work a used guitar might require once you bring it home. Remember, pretty much every guitar will need at least a setup (running generally between $60 and $100), so roll that in to your budget from the get-go. A note: The prices I mention below are a general idea and can vary—a lot—depending on where you live and the experience level of your tech. If you are tempted to bargain shop when getting a repair quote, don’t simply hire the lowest bidder! You will get the repair you pay for, especially in the case of a vintage guitar.

So to start, give the guitar a…

VISUAL ONCE-OVER

Hold the guitar in your hands, and really have a look at the top, back, and sides. Finish can tell us a story about what’s happened to the guitar; you can see if it’s been damaged by moisture or an impact. Does the finish look pretty consistent? Do any dings or flaky areas catch the eye?

Are there any gaping cracks or seam separations in the body? If the exposed wood isn’t dark and the two sides haven’t warped away from each other—an indication of being open for a long time—cracks are not the end of the world. Likewise, a neatly repaired seam or crack doesn’t worry me too much. If seams are open or there are cracks in need of repair, you’ll need to add $50–$150 to your repair bill.

Have a look at the bridge. Is it glued down firmly? Try to slide a piece of paper under the back edge and corners. If it goes under any part of the bridge at all, the bridge needs to be removed and re-glued. This crucial repair cannot wait. If you don’t have a solid glue joint, the sound will suffer, and the top will be stressed and pulled in ways that it wasn’t built to withstand. I recommend keeping the tension off of a guitar until this repair can be done. Imagine adding $150–$300 to your repair bill.

Next, look at the neck joint. Does anything look out of place? Is the finish chipping or discolored along the bottom edge of the heel? This could reveal a previous neck reset, which is not such a bad thing if it was neatly done—it means you don’t have to pay for it! Lots of guitars, including almost all vintage Martins, will need a neck reset in their lifetime. I’ll talk more about how to spot a future neck reset in the next column.

ADVERTISEMENT

NECK CHECK

Now let’s talk about the neck—a crucial element in a guitar’s health. A bit of relief is nothing to worry about, but a lot of relief, a twist, or a rollercoaster up and down are potentially deal breakers. There are a couple of ways to look for a neck’s straightness. Here’s what I do first: I set the lower bout of a guitar down in front of me, and, pointing the neck right at me, I lift the headstock up to one eye. Closing the other eye, I sight along the neck, using foreshortening to see how straight each side of the neck is. This helps to see big irregularities, dips, humps, and slopes.

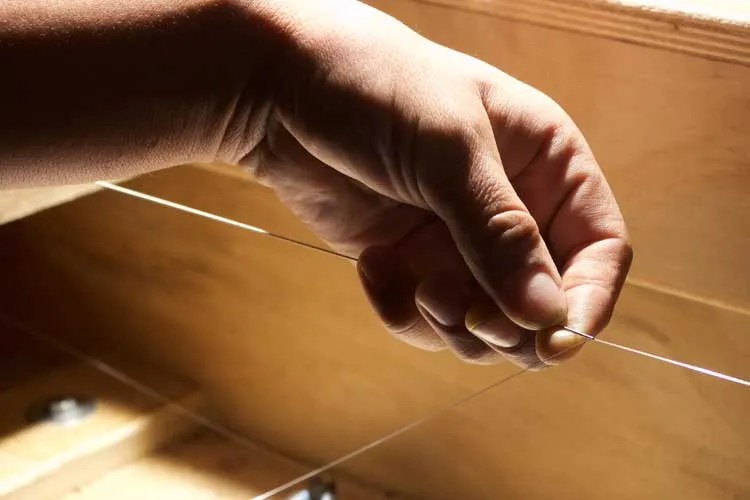

If you have a hard time getting this to work for you or want a more precise take, come prepared with an 18-inch straightedge and lay it along the tops of the frets while the guitar is strung up to tension. You’ll be able to see how much relief is in the neck. A good aim is to be able to slip a 0.010-inch feeler gauge under the string at the eighth fret. You and your luthier can tweak it from there.

PLAY THE DARN THING

If all looks acceptable to you, here’s your chance—sit with the guitar and play some tunes. Bring what you need to give it a good test drive: your favorite pick, a capo, perhaps a generous friend who can sit across from you and tell you how it sounds out in the room. Ask the guitar to do all the things you wish it would, and take note of any ways it falls short. Here is a good chance to get a feel for the neck, and to see how healthy the frets are. If there are a couple of high or low ones, a fret-dress will likely work, and cost you somewhere from $50 to $150, but if they’ve been played flat and dressed a couple of times already, it’s time to replace them. A refret is more expensive if your fingerboard is bound, or is made of maple or a very brittle ebony, so it would likely cost between $250 and $600.

When you’re searching for a new-to-you guitar, it pays to be curious about all aspects of your potential instrument’s well-being. So far in this series, I’ve talked about ways to shop for vintage or used guitars: doing a basic once-over to find any issues, scrutinizing a neck, what to think about cracks and seam separations, how to tell if a bridge needs to be re-glued, and what a difference a refret can make.

In this installment I’d like to talk about a couple of ways to get deep when assessing a guitar. First, have a peek inside the body. It’s helpful to bring a mirror and flashlight along when you go to look at a guitar. Think about it like popping the hood on a car—if you know what you’re looking at, you can tell a lot.

As always, the prices I mention are a general range. Costs can vary—a lot—depending on where you live and the proficiency of your tech. Don’t be tempted to bargain shop when getting a repair quote! Repairs are like tattoos: you get what you pay for.

Bridge Plates

ADVERTISEMENT

One big reason I look inside acoustic guitars is to check out the bridge plate. This piece of wood—often maple, but sometimes rosewood or another wood—reinforces the top and plays an important role in a guitar’s sound and sturdiness.

When you look at a bridge plate, you want to see the strings’ ball ends and the bridge pins popping down through holes that are clean and circular. Sometimes you see a bad pattern of wear. It could be because a softer wood was used to make the bridge plate or because of how it’s been handled. The holes can be ragged or worn, and the wood between them may have been gouged away.

Sometimes, if a bridge that’s pulling up goes unglued for a long time, the bridge plate will actually split. If the wear is bad, it may need to be repaired or replaced. This could cost anywhere between $75 and $400, because removing a bridge plate is tough and can be unpredictable.

Check out the rest of the inside of the box. If there are cracks, you’ll be able to see if cleats—thin wooden patches—have been used. A couple of cleats and a neatly repaired crack or seam separation are not the end of the world. These fixes generally don’t affect the sound, and you can tell something about the quality of work a guitar has endured by having a look at how neatly this has been done.

ADVERTISEMENT

Neck Resets

The last thing I want to cover is neck angle, and whether a guitar might need a neck reset. Of course, over time, strings put lots of tension on a guitar. Certain things are bound to give to that tension, and, as the angle of a neck pulls forward and the slight arch built into a guitar’s back flattens out, you might find that the action gets higher and higher. Sometimes, problems are easy to spot: a very short saddle or a bridge that has been shaved down reveals that a previous repairperson tried to fudge things and lower the action without resetting the neck. The guitar won’t sound as good as it could; the break angle over the strings will be shallow and the strings won’t vibrate the top as much as they should.

Here’s a quick way to get a general idea of neck angle, but it only works with a pretty straight neck and a full-height bridge. Take an 18-inch straightedge and lay it along the fretboard so that the end touches the bridge. If it sits just on top of the bridge, or almost does, that’s probably a pretty good angle. If it dives towards the top, the angle is too forward, or shallow, and the guitar could need a neck reset.

Don’t let these words make you feel panicked: lots of great guitars, including most vintage Martins, end up needing their neck angle reset over the course of their life. Thinking about price, remember that a reset is a major repair, and some shops always do a refret at the same time. This makes it a hard repair to price, as it could run anywhere from $350 to $1,000.

Even with a repair or two to consider, you still stand to get more for your money when shopping used or vintage. And of course, you can’t reproduce the mojo of a cool old guitar. Hopefully this guide helps you find the perfect, broken-in guitar of your dreams.