Learn the Essential Techniques of Fingerstyle Acoustic Guitar

Keith Richards has said that when he first heard the solo recordings of famed bluesman Robert Johnson, his first question was “Who’s that?” and his second was, “Who’s that other guy playing with him?” But there was no other player. Johnson was of course conjuring up the sound of simultaneous rhythm and lead guitars by playing fingerstyle.

Fingerstyle guitar is a technique that uses the thumb and fingers to sound individual strings instead of relying on a pick. The ability to leverage individual fingers allows guitarists to play multiple parts at once, with separate bass lines, melodies, and accompaniment, often leading those who first hear a fingerstyle recording to think they are hearing more than one guitar.

Just as the term flatpicking often implies a certain musical style and not just the technique of using a pick, fingerstyle sometimes brings to mind a specific genre of instrumental guitar. But taking a wider view, fingerstyle encompasses a huge range of musical styles—classical, flamenco, jazz, folk, world music, and beyond—all bound together by a fundamentally similar technique. Here we will explore these styles, along with a bit of the history of fingerstyle guitar, and some of the more influential players who have applied the technique to different genres. It will also present a variety of examples to get you started with this versatile and essential approach to guitar.

The Classical Tradition of Fingerstyle Guitar

The history of fingerstyle guitar mirrors the history of the guitar itself in many ways. Early ancestors of the guitar were often plucked with a quill—the predecessor of the pick. But with the development of the lute, by the early 1500s players began using their thumb and fingers to produce polyphonic music. John Dowland was one of the best-known lutenists in England and his compositions remain popular with guitarists to this day. Bach also composed for the lute; his “Bourée in E Minor,” an excerpt of which is shown in Example 1, is a staple among guitarists and an excellent example of independent musical lines that require fingerstyle technique to perform on a single guitar.

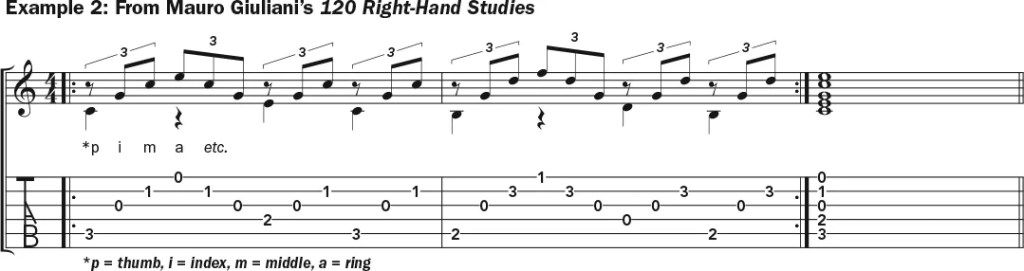

Instruments that looked very much like modern classical guitars began to appear in the 1700s. Mauro Giuliani and Fernando Sor were well-known performers and composers who wrote complex pieces for the instrument, and their works remain core parts of classical guitar studies. Example 2 is a snippet from Giuliani’s 120 Right Hand Studies, a collection that offers great ways to develop fingerstyle technique for classical and other players.

Classical-guitar technique evolved to have fairly rigorous rules for the right-hand, involving picking with flesh and a bit of nails, and having two main strokes: apoyando (rest stroke), in which the finger comes to rest against an adjacent string after a note is picked, and tirando (free stroke), which does not involve any resting.

Few players have been as influential in the development of classical technique and repertoire as Andrés Segovia, perhaps the most celebrated proponent of the instrument. In a career that spanned more than 80 years, Segovia set the stage for newer generations of virtuoso classical guitarists, including Ida Presti, Julian Bream, John Williams, Christopher Parkening, Sharon Isbin, and many others who would help further expand the scope and repertoire of

the instrument.

ADVERTISEMENT

Spanish and South American Strains

Flamenco guitar developed in Spain in the mid-1800s, primarily as a percussive accompaniment for dancers, and the word flamenco refers to the dance. Example 3 demonstrates a typical flamenco strumming pattern, alternating between downstrokes of the thumb and upstrokes of the index finger. In each bar, note the percussive hit (golpe) on beat 3 and the accents on beats 2.5 and 4, which emphasize the rhythmicity of this spirited, dance-informed music.

Flamenco guitar evolved away from being strictly for accompaniment. Ramón Montoya is credited as one of the first flamenco musicians to explore the potential of guitar as a solo instrument. His nephew Carlos Montoya expanded flamenco’s popularity by adapting it to other types of music, including blues and jazz, performing with orchestras and touring in the United States.

Further developing the potential of flamenco guitar, Paco de Lucía became a leading figure in nuevo flamenco, applying his prodigious technique to jazz in collaborations with guitarists John McLaughlin and Al Di Meola, as heard on the classic album Friday Night in San Francisco (1981). De Lucía’s adventurous influence is apparent in the work of a new generation of players, such as Gabriela Quintero, one-half of the dynamic duo Rodrigo y Gabriela, which blends traditional fingerpicking with flamenco-inspired strumming and rock and percussive elements.

The music of South America has also played a big role in the development of fingerstyle guitar. Brazil in particular has produced countless significant fingerstyle performers and composers who blend classical techniques with the music of their country, including Heitor Villa-Lobos and Carlos Barbosa-Lima. In the late 1950s, Antônio Carlos Jobim, Baden Powell, and Luiz Bonfá helped introduce the world to Brazilian/Latin rhythms including bossa nova, which blends classical and jazz with samba and other South American styles.

Example 4 shows a typical bossa nova accompaniment pattern, most commonly played on a nylon-string guitar, in a smooth and lilting way. The bass notes are picked squarely on beats 1 and 3 by the thumb, while the index, middle, and ring fingers add syncopated jazz chords above.

A Sea Change

Guitars from the 1500s to nearly 1900 were generally based on gut strings, but beginning in the late 1800s builders like the Larson Brothers began using steel strings. Part of the appeal of steel-string guitars was volume, along with brighter and more percussive sounds, making them good rhythm instruments, but players soon began using fingerstyle techniques on the new instruments as well.

Example 5 is representative of country blues accompaniment, one of the earliest uses of fingerstyle on steel-string guitars. Here, the thumb plays a steady monotonic bass on the low E string against a rhythmic riff played using fingers on the three treble strings. Try muting the bass notes by lightly resting your hand on the bass string near the saddle and picking the bass string fairly hard to create a percussive, driving effect.

Blues and ragtime guitarists like Charley Patton, Blind Blake, Big Bill Broonzy, and Robert Johnson were among the pioneers who recorded in the 1920s and 1930s. Many other players were all but forgotten until they were rediscovered in the 1950s/early ’60s folk boom—among other influential players, Reverend Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt, Fred McDowell, Skip James, John Lee Hooker, Son House, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Elizabeth Cotten, whose song “Freight Train” is one the first fingerstyle tunes many players learn.

ADVERTISEMENT

These legends inspired a new generation of guitarists like Rory Block, who built her career playing blues in the tradition of her mentors, including Reverend Gary Davis and Mississippi John Hurt. Other guitarists, like Eric Schoenberg and his cousin David Laibman, were more influenced by the ragtime side of things. Schoenberg’s formidable arrangements of pieces like Charles L. Johnson’s “Dill Pickle Rag” (transcribed in the September 2018 issue) raised the bar not just for ragtime players but for steel-string fingerstyle guitarists in general.

A slightly different approach emerged when the country-and-western guitarist Merle Travis, inspired by his fellow Kentuckian Mose Rager, developed the right-hand approach that came to be known as Travis picking. In this style, the thumb alternates between two bass strings, while the higher notes are picked either at the same time or between bass notes, which are often palm muted for textural effect (Example 6). It is difficult to overstate the widespread influence of this approach, which is the default accompaniment pattern used by so many folk singers and guitarists to this day. Travis picking also featured extensively in the style of Chet Atkins, one of the most widely known of all guitarists, whose approach to the guitar would be the blueprint for virtuosos like Tommy Emmanuel, John Knowles, and Steve Wariner.

The Folk Scene

Steel-string techniques played an essential role in the folk realm, with groups and singer-songwriters like Peter, Paul and Mary, Paul Simon, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, and Joan Baez using the guitar to accompany their vocals in creative ways. At the same time, starting in the late 1950s, solo guitarists took fingerstyle to exciting new places. John Fahey was initially influenced by early blues players but also incorporated elements inspired by 20th-century classical composers like Béla Bartók. Fahey’s approach came to be known as American primitive guitar; other practitioners of this idiosyncratic approach have included Robbie Basho, Peter Lang, and Leo Kottke, who released his seminal album 6- and 12-String Guitar on Fahey’s Takoma Records label in 1969. Fahey and his cohorts continue to influence young generations of players, including fingerstylists Gwenifer Raymond and Yasmin Williams.

Peter, Paul, and Mary perform at the March on Washington, 1963. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Meanwhile across the pond, steel-string guitarists developed a style sometimes known as folk baroque. Players like Davey Graham, Bert Jansch, and John Renbourn fused fingerstyle blues and ragtime with English medieval folk and classical songs, using both standard and alternate tunings. These concepts would spread to popular music in general. Around 1968, for instance, the singer-songwriter Donovan taught John Lennon and Paul McCartney some simple fingerpicking patterns, leading to songs such as “Julia” and “Blackbird,” the inspiration for Example 7, and introducing fingerstyle to a vastly larger audience.

The influence of the folk baroque movement inspired players like Pierre Bensusan and Martin Simpson to take fingerstyle technique to impressive new heights in their complex arrangements and compositions, which are often jazz-infused. And traditional music, most prominently Celtic, has also been the basis of the music of contemporary fingerstyle forces like Tony McManus and Steve Baughman.

In a different direction, another rootsy style developed in the Hawaiian Islands. The guitar first came to the Islands during the 19th century, brought by Mexican cowboys (paniolos), but it was native Hawaiians who explored the instrument on their own and discovered that the guitars sounded better to them if they were tuned to open chords. Because they slackened (or lowered) the strings, the style became known as slack key. Pioneers such as Gabby Pahinui, Leonard Kwan, and Sonny Chillingworth combined Hawaiian folk tunes and rhythms with fingerstyle techniques, and later players like Keola Beamer and Ledward Kaapana developed the style into a more sophisticated contemporary sound.

Like Travis picking, slack-key guitar often employs an alternating-bass approach, frequently combined with a melody harmonized in diatonic sixths. Example 8, in open-G tuning, demonstrates a simple melodic phrase followed by a typical turnaround lick. Open G is known as “taropatch” tuning by slack-key guitarists, and is just one of an extensive set of alternate tunings common among slack-key players.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nonstandard Tunings and Extended Techniques

In the late 1970s, guitarist William Ackerman launched the Windham Hill Records label, introducing his own music, as well as that of his cousin Alex de Grassi, Michael Hedges, and others. Though sometimes categorized as new age because of its gentle accessibility, the Windham Hill sound is actually quite sophisticated, involving complex fingerstyle arrangements that often leverage nonstandard and unusual tunings.

Patterned after the Windham Hill sound, Example 9 demonstrates a few typical characteristics in a Dsus2 tuning, like DADGAD, but with string 3 tuned down a minor third (low to high: D A D E A D). The last bass note in measure 1 and the first bass note of the following bar should be played by simply tapping the note with the fretting hand to create a different texture.

Hedges in particular employed an array of novel techniques to support his compositions, including percussive effects, slap harmonics, double-handed tapping, and string damping. Don Ross, and later Andy McKee, further developed these techniques, launching a percussive fingerstyle approach that revealed new sonic possibilities inherent to the guitar.

Players like Kaki King, Christie Lenée, Jon Gomm, and Alexandr Misko have developed percussive techniques even further, using highly choreographed hand movements to produce layers of sound from a single guitar. Example 10 shows how to apply some typical percussive techniques in DADGAD tuning, with snare, tom, and kick drum effects created by tapping the guitar’s top and side, as seen in the accompanying video.

ADVERTISEMENT

A World of Music to Explore

Andrés Segovia referred to the guitar as a small orchestra, and whether listening to a sophisticated classical piece, fingerstyle country-blues, or a contemporary percussive player, it’s easy to understand why. When playing fingerstyle, you can be the entire band. Even the simplest fingerpicking pattern produces a satisfyingly full sound, while more complex arrangements can create the illusion of multiple instruments playing together. And because the technique is applicable to any musical style, from blues to classical to jazz, the opportunities are unlimited. Fingerstyle, like the guitar itself, has the benefit of allowing beginners to produce musical sounds relatively quickly and easily, but you can also spend a lifetime exploring the technique and never exhaust the possibilities.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2021 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.

Many of the teachers who contribute lessons to Acoustic Guitar also offer private or group instruction, in-person or virtually. Check out our Acoustic Guitar Teacher Directory to learn more!