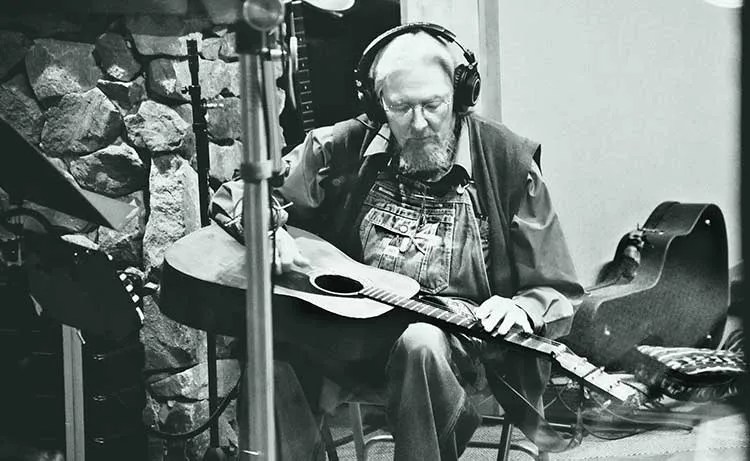

How to Flatpick Like Roots Legend Norman Blake

Often described as one of the great unsung heroes of 20th-century folk music, it’s hard to imagine that Norman Blake, never one for the spotlight, would want it any other way. Blake has kept a low profile, living the majority of his life in the quiet northwestern corner of Georgia. But his accolades are dizzying: He has worked as a studio musician and sideman for some of Nashville’s greatest stars; his songs have been covered by the likes of Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings, Tony Rice, and the Punch Brothers; he has received a multitude of Grammy awards and nominations; and he is considered one of the finest and most influential flatpickers ever. And though Blake stopped touring in 2007 to enter retirement, at the age of 83 he continues to play and record, with his most recent album, Day By Day, released last October by Smithsonian Folkways.

Early Life

Norman Blake was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1938, shortly before his family relocated to Sulphur Springs, Georgia. Growing up, his family listened to the Grand Ole Opry and other programs on a battery-powered radio, and it was there that he heard the musicians that would influence him throughout his entire career: Roy Acuff, Maybelle Carter, and Riley Puckett. His first guitar was an inexpensive Stella he got around age 12 that he played fingerstyle, and soon after that he learned mandolin and dobro.

At 16, Blake dropped out of school to play mandolin professionally, and by 19 he was working with the bluegrass and country musician Hylo Brown, touring as part of June Carter’s band, and doing session work. He was drafted in 1961 and served for two years in Panama, returning home in 1963 to resume his work as a performing musician and guitar instructor. Blake first heard Doc Watson’s music through one of his students; he was amazed by Watson’s approach, and at that time began developing his own flatpicking skills by transferring them from mandolin to guitar.

Session Work and Solo Career

Blake started picking up session work in Nashville around 1963. During one of these sessions, June Carter introduced him to Johnny Cash, who was in search of a dobro player and hired him on the spot. Blake borrowed a dobro from Josh Graves (of Flatt & Scruggs) and recorded with Cash the next day for the song “Bad News.” He recounts that after the first take, Cash told him, “Well that’s real good, but that’s too good for one of my records. Can you play about half as much and play it on single strings?” The guitarist did just that, and continued to record with Cash for the next 40 years.

Over the next decade, Blake toured extensively and contributed to a multitude of essential folk classics, including Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline (1969), John Hartford’s Aereo-Plain (1971), Joan Baez’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” (1971), the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will The Circle Be Unbroken (1972), and Doc Watson’s Elementary, Doctor Watson! (1972). During this time he met Nancy Short (later to become his wife), and the two would perform together for over 20 years and be nominated for four Grammys.

In the early 1970s Blake was touring with John Hartford when Bruce Kaplan of Rounder Records invited him to make a record. Blake said he wouldn’t put out an album until he had some original material, but with the offer on the table he soon started writing and then recorded his first solo outing, Back Home in Sulphur Springs, in 1972. That disc, along with many others he would release over the years—including recordings with his wife, duet outings with Tony Rice, and genre-defying releases with the Rising Fawn String Ensemble—form a treasure trove of original songwriting, American folk classics, and stellar acoustic flatpicking.

ADVERTISEMENT

Blake’s big break came late in his career, with his contribution to the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack (2000), which sold eight million copies, won multiple Grammys, and gave Norman and Nancy Blake the opportunity to ease into retirement from touring. He gained further visibility by appearing on another Grammy-winning success: Robert Plant and Allison Krauss’ Raising Sand (2007). Though Blake now appreciates a quiet existence away from the road, the musical life for him has never stopped. He has continued to release albums and play at home, even despite a mini-stroke in 2012 that left him unable to sing and play for some time. In 2017, when he recorded Brushwood (Songs & Stories), he told The Bluegrass Situation, “I think maybe this might be my last one—my last full record that I’ll make.” Yet thankfully here we are with Day By Day, another lovely gem from Blake.

Flicking Water from the Fingers

The most notable aspect of Blake’s playing is his loose right-hand approach, which translates into a relaxed and flowing feel—even at very fast tempos. He said he developed this style when learning to play mandolin, and describes the motion as like “flicking water from the fingers.” His hand movement, both for strumming and single-string picking, is primarily a rotation from the forearm. He does not brace his hand at any point on the guitar, but rather drapes his pinky and ring fingers over the pickguard and lets them loosely graze across the top as he picks.

Blake’s style has never been flashy, and instead is focused on accentuating the song’s melody and feel. The guitarist doesn’t use memorized licks and has never been one to copy somebody else’s playing. Rather, he says that his style focuses on channeling “the mood, the overall vibe, and the feel” of a song. For this reason there aren’t really any signature Norman Blake licks, and understanding his style is more about dissecting his articulation, feel, and technique.

Blake’s rhythm approach builds on the common boom-chuck pattern, often weaving together a variety of different rhythm patterns to fit a song’s particular style and cadence. Here is a set of three such figures that demonstrate some of Blake’s typical patterns over an open G chord. Example 1a is the version he uses most often. It starts with a boom-chuck—striking the low G note, strumming the treble strings, and then sounding the D string, all in downstrokes. It then uses alternate picking to play an upstroke on the G string and a down-up strum on the top two strings.

The magic of Blake’s rhythm is a pulsating effect that comes from varying dynamics throughout the measure. There is an accent on the “booms” of the pattern (beats 1 and 3), and a quick volume swell on the strum of beat 4—best understood by carefully listening to his playing. Some good recordings that show off Blake’s unaccompanied rhythm at moderate tempos are “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” (on Directions) and “Are You From Dixie” (Blackberry Blossom).

Example 1b shows another rhythm pattern Blake often uses, again beginning with a boom-chuck and then transitioning into a crosspick across the treble strings. Similarly, Example 1c replaces the first boom-chuck with a crosspick as well. An excellent demonstration of these two patterns is in the introduction to “Bringing in the Georgia Mail” (Back Home in Sulphur Springs), which uses a classic Riley Puckett–inspired bassline at breakneck speed. Example 2 shows a slightly simplified version of the intro as an illustration—Blake’s actual rendition uses the same motion, but with a looser hand that intentionally strikes multiple strings at once.

Blake would continue to use this articulate and pulsing rhythm approach while playing backup. “Little Joe” (Sulphur Springs) highlights this exceptionally well, and Example 3 presents the bass pattern he uses to back up the mandolin solo. The rhythm approach continues to mix and match from Exs. 1a–c, while the bass moves between chord tones and walking bass lines. Meanwhile, the chord shapes played on the treble strings also change. If this approach is new to you, keeping track of the rhythm patterns, chord shapes, and bass runs may seem like an impossible task, but just work on each of these elements individually and in time it will all meld together.

A Subtle Skill

Blake’s prowess as a flatpicker comes not only from his ability to play intricate fiddle tunes at blistering tempos, but also in providing his own self-accompaniment while doing so. He does this by playing the melody of the tune in one register of the strings while accompanying with chordal harmony on the other set of strings. It is a subtle skill: As a listener, it is easy to be amazed by his speed and fluency while not recognizing he is also supporting the tune by playing backup chords simultaneously.

A fine example is “Under the Double Eagle” (Whiskey Before Breakfast). Example 4 illustrates the approach, in which the melody is in the bass and the accompanying chords are on the treble strings. The right hand in bars 1–3 is much like the rhythm patterns shown above, and bar 4 switches to crosspicking. Through much of the passage, Blake keeps his first finger on the first fret of the second string (C), so that it and the open strings continue to ring while the melody passage is played underneath.

ADVERTISEMENT

Another great instance of Blake’s self-accompaniment is on his version of “Arkansas Traveler” (Live at McCabe’s).His first pass of the melody is approximated in Example 5. Like the previous example, the melody is on the bottom while the accompanying chords are on top, and this pattern continues even into the B section where the melody goes as high as the open G string (bars 9 and 13). Also notice how the melody line is interspersed with the same rhythm strums from Ex. 1a, like in the second half of bar 1 and all of bar 2. On the record, Blake plays the tune several times through with many variations; the version here is inspired by his first time through and is closest to the traditional melody.

Jaw-Dropping Solos

Blake often incorporates speedy single-note runs into his soloing approach. Drawn from the chromatic scale, these passages form a rapid succession of notes linearly rising and falling across several measures and often across all six strings of the instrument. An illustration is shown in Example 6, inspired by one of Blake’s many jaw-dropping solos on “Nine Pound Hammer” (Live At McCabe’s). Note the quick triplet passages, played with a slide in bar 4 and hammer-ons and pull-offs in bar 7. Also notice how even though Blake uses chromatic patterns throughout, he is clearly abiding by the underlying harmony, for instance outlining a C chord in bars 3–4 and D in 5–6.

All of the previous examples are from Blake’s earlier recordings as a solo artist and showcase his technical skills as a flatpicker and rhythm guitarist. As his career continued, his playing relaxed into a more subtle and nuanced approach that favored melodic content and simplicity. One of my favorite selections is his take on the classic “Maple on The Hill” (Far Away, Down on a Georgia Farm), the introduction of which is the benchmark for Example 7.

Played with no capo in the key of F, the lovely arrangement incorporates some of the same techniques shown above: self-accompaniment, crosspicking, and the modified boom-chuck strum. Unlike the previous examples, the melody sometimes happens above the chords (like during the crosspicking in bar 2) and sometimes below (as in the strummed passage in bars 3–5), and Blake effortlessly weaves these together while keeping the melody in the forefront. Characteristic of his later recordings, he also uses successive downstrokes that highlight bass passages and provide an old-timey effect, like in bars 16 and 21.

Time Behind the Box

When asked about the best advice he has for aspiring players, Blake says, “When it comes to playing guitar, there is no substitute for time behind the box.” He adds, “If you have any kind of natural inclination towards music, do your own thing as much as possible. Don’t try to copy somebody’s licks note for note, because you’re never going to be coming from where they are. Most of the time a lot of the good players are coming out of their own head so it’s spontaneous within them, and if you try to copy them the spontaneity factor is not there. Play out of your own head and heart as best you can.”

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from Blake’s playing is that he developed his own style because that’s what worked for him. No one can sound exactly like Blake, because no one has had his exact same experiences or influences. But by studying his thoughtful style and approach, you can learn to sound a little bit more like yourself.

Blake’s music is nothing but pure self-authenticity. There is no flash or trickery, just heartfelt musicianship that brings forth the true essence of the songs and melodies. His quiet and humble attitude toward music is articulated succinctly in the final few lines of “Church Street Blues,” one of his most beloved songs: “I’ll just stay right here just pick and sing a while, try to make me a little change and give them folks a smile.”

ADVERTISEMENT

What He Plays

Norman Blake recorded his early solo albums—including the flatpicking showcases Whiskey Before Breakfast and Live at McCabe’s—on Martin dreadnoughts. Soon after, he began to opt for 12-fret guitars, which he prefers for their bigger tone and more open sound. “I’ve always maintained that the fact that it joins the body at the octave—on the strongest harmonic point there at the 12th fret—has something to do with it,” Blake says. Throughout the 1980s he often used a 1934 Martin D-18H, later switching to smaller-bodied models, like a 1929 Gibson Nick Lucas Special. He avidly buys and sells vintage guitars, never sticking to any particular one for long, instead choosing instruments whose voices best meet the task at hand.

These days Blake owns a number of instruments but says he is mostly playing a 1928 Martin 00-45, a guitar that his wife often took on the road. He recorded all the solo tracks on Day by Day using a guitar called a Nancy Blake Special, built by John Arnold in Newport, Tennessee. The instrument is similar to a Martin 000 12-fret but has a deeper body, shorter scale, and larger soundhole. There were only two such guitars made: Nancy received the first, and over the years Norman ended up acquiring the other. For the other tracks on Day by Day he used a 1937 Gibson J-35.

Blake has also been known to experiment with string and pick choices. He orders strings individually, mixing gauges to find the set that highlights the features of each specific guitar. Though the gauges have varied over the years and by instrument, he typically uses lighter gauges on high strings (.011 for high E) and heavier sizes on low strings (.060 for low E). For picks he either uses a Fender Extra Heavy tricornered pick (that he files down to round and bevel the edges), or the back edge of a D’Andrea Pro Plec. A few new signature models from Apollo Picks emulate Blake’s approach to pick size, shape, and beveling, and the guitarist uses these plectrums as well.

Alan Barnosky is a roots guitarist and singer-songwriter based in Durham, North Carolina.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many of the teachers who contribute lessons to Acoustic Guitar also offer private or group instruction, in-person or virtually. Check out our Acoustic Guitar Teacher Directory to learn more!